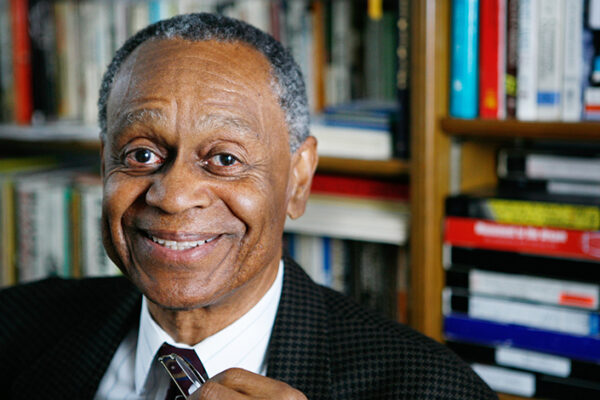

While growing up in Boston’s inner city, Eric Carson didn’t think African Americans, like himself, could become physicians. But not only did he become a physician, he chose to work in orthopedics, a specialty noted for its lack of diversity.

Carson, one of four children raised by a single mother, was bused along with his siblings to more affluent, predominantly white suburbs for elementary and high school. To fill their free time, his mother enrolled them in a variety of activities run by nonprofit organizations such as the Boys & Girls Clubs of America.

“My mother is a hero from the perspective that she kept us all busy,” said Carson, now a professor in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. “And the beauty of it all is that her sacrifices paid off for all four of her kids.” He and his siblings all have graduate degrees and successful careers.

As a youth, Carson became an avid athlete, playing high school and college football, running track and becoming a member of a ski team. “I excelled in football at Tufts University, enough to receive invites to professional football training camps for the fledgling United States Football League (USFL),” said Carson. But instead of pursuing his football prospects, he decided to attend the University of Illinois College of Medicine in Chicago for medical school.

From there, getting into orthopedics proved challenging. After Carson aced his Step 1 licensing exam, his adviser discouraged his interest in orthopedics, a highly competitive specialty with few underrepresented minorities in its ranks, particularly at the time. But with encouragement from a friendly resident he knew, Carson found a new mentor and surprised his class when he matched into orthopedics at Harvard University, back in his hometown.

Haunting experience

During his residency in Boston, Carson was walking down the street early one morning, on his way to rounds at the hospital. Suddenly, Boston Police officers appeared, wrestled him to the ground, handcuffed him and pointed a gun at his head, he recalls. They had been looking for a Black suspect in the recent murder of a pregnant woman. The victim’s husband had blamed the crime on a “Black man” with a physical description similar to Carson’s. The husband later admitted to killing his wife and then died by suicide. But the incident continues to haunt Carson to this day.

The episode is a reminder to Carson to not let his guard down, especially in light of the killings by police of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and other unarmed Black people. He has made a point of stressing to his son, a Black man in his 20s, to always remain vigilant. Carson has been very open about his experiences, sharing them widely, particularly within the medical community.

While the incident in many ways changed Carson, he was careful to not let it stop his momentum. His time in residency ultimately was extremely rewarding.

“One amazing highlight of my Harvard University experience was working hand and hand with my mother,” he said. She was an orthopedic nurse at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), one of the hospitals where Carson worked while in Boston. “The proud look and smile my mother displayed regularly was infectious and directly related to my accomplishments.”

The two spoke every day until she died Dec. 1, after a battle with cancer. Carson is dedicating a grand rounds talk he has been giving about his life to her.

Read his full profile on the School of Medicine site.