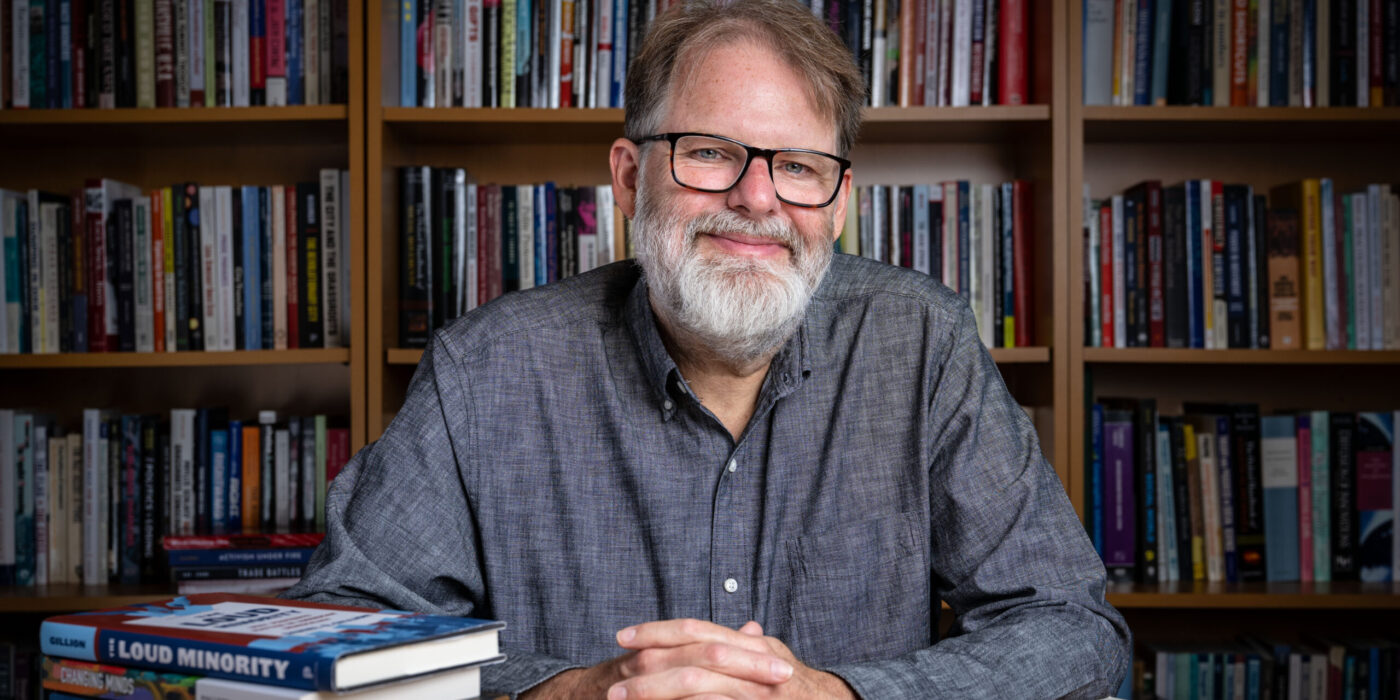

For centuries, protest has been a powerful force in societies, influencing politics, media and daily life. The past 20 years, in particular, have been marked by unprecedented levels of activism, according to sociologist Kenneth “Andy” Andrews, Tileston Professor of Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

Governments, businesses and culture, however, have been slower to change.

“We’ve been witnessing so much activism, but relatively modest indicators of the political power to translate that fervor into institutional change,” said Andrews, whose historically based scholarship is yielding new insights into how social movements may achieve widespread awareness and policy change today.

From Civil Rights to Black Lives Matter and beyond

Andrews grew up in Pensacola, Fla., during the 1980s, in a family that wasn’t especially political, but was always aware of, and discussing, current events, he said.

“Growing up in the South in the post-civil rights period, I was curious about what had or hadn’t changed as a result of that social movement, as well as the pushback against policies like school desegregation and affirmative action,” Andrews said. “The conservative ideas that came out of the 1980s represented a pendulum-like response to the Civil Rights Movement of the ’50s and ’60s.”

Andrews began his undergraduate career as a pre-med student at Millsaps College in Jackson, Miss. — a city that played a vital role in the Civil Rights Movement. Inspired by his courses, and perhaps his surroundings, he quickly changed his major to sociology. During this time, Andrews also co-led a campus group that advocated for policies to address hunger and poverty at a national level. That experience in activism furthered his interest in the power of social movements as well as the challenges they face.

“We faced a lot of difficulty enlisting support from Mississippi’s congressional delegation, but it was exciting to work with groups from across the country to push for changes,” Andrews recalled.

After earning a bachelor’s degree in sociology from Millsaps in 1990, Andrews pursued a master’s degree and PhD in sociology from the State University of New York at Stony Brook.

Initially, Andrews considered focusing on several different sub-fields of sociology, but he returned to his longstanding interest in social movements. “Sociologists typically study the ways in which society is reproduced through social interactions and structures. But social movements are about disrupting and trying to change those enduring patterns of inequality. That was very exciting to me,” he said.

Andrews was especially drawn to understanding the ideas of civil rights activists such as Ella Baker, Bob Moses and Anne Moody.

“In graduate school, I started digging deeper and reading about the organizations and strategies being developed by Black college students in the early 1960s. They wanted to avoid having a single charismatic leader that drives their movement,” Andrews said. “I wanted to understand how you can create an organization that’s innovative, one that creates new leaders and doesn’t become beholden to the status quo.”

That interest led Andrews toward a 20-plus-year career studying the dynamics and legacy of the Civil Rights Movement in the U.S. South. He is the author of “Freedom is a Constant Struggle: The Mississippi Civil Rights Movement and Its Legacy,” published in 2004 by the University of Chicago Press, as well as more than a dozen scholarly articles on the topic. He also has studied the leadership, participation and influence of environmental groups and the local and state politics of Prohibition.

Andrews’ historical research took on new meaning with the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2013. Today, Andrews, who also directs graduate studies in WashU’s Department of Sociology, is tracing the evolution of Black Lives Matter activism in different cities — from the killing of Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Fla., to George Floyd in Minneapolis. He is also examining the dynamics of local civil rights movements in the South, focusing on how local organizing can produce bigger waves of protest.

This comparison of different places — some with weaker and some with stronger movements — has guided Andrews from his dissertation to the present moment.

“We’re asking why these local movements generate power beyond what you might be able to produce in St. Louis, or what gains you might make in Birmingham,” Andrews said. “The analytical question we ask is how places evolve differently over time and how movements contribute to those changes.”

“Social movements are in a David-and-Goliath scenario, so we wouldn’t expect them to always win or have an advantage that makes it easy to accomplish things. But sometimes they do have profound impacts, and we need to understand why.”

‘Social movements are in a David-and-Goliath scenario, so we wouldn’t expect them to always win or have an advantage that makes it easy to accomplish things. But sometimes they do have profound impacts, and we need to understand why.’

Kenneth “Andy” Andrews

A changing landscape

With the advent of social media, movements have found new ways of circulating ideas without the need for face-to-face connections, Andrews explained.

“In the past, social movements relied on communities like churches and schools, where people already had long-standing connections, to spread their ideas, recruit participants and sustain their cause,” Andrews said. “With social media, movements can more easily gain attention and mobilize people.”

But social media has its downsides. “The enthusiasm for movements can fade quickly if it’s only propped up by social media, so leaders have to figure out ways to build more enduring relationships and organizations if they want to have lasting impacts,” Andrews said.

In an age of increasing political polarization, movements also must find ways to strategically communicate to supporters while also reaching those who may be disengaged or skeptical of their cause. While TV and social media rapidly disseminate information, audiences often exist in an echo chamber.

“Many people are consuming media in ways already motivated by their political ideologies. They are isolated from information that differs from their preferred way of seeing the world,” Andrews said.

This polarization makes cooperation difficult and change slow to materialize, with activists frequently finding themselves in a stalemate with local and national governments, he said.

“Over the past six decades, the window for bipartisan legislative activity has gone from relatively routine to zero, and that changes the political calculus for social movements if they’re interested in trying to influence national policymaking,” Andrews said.

Despite the enduring challenges of bringing people together and sustaining commitment — as well as more recent efforts to crack down on peaceful protests and silence dissent — activists are not giving up. And as long as activists are showing up and fighting for social change, Andrews will be there to study their work.