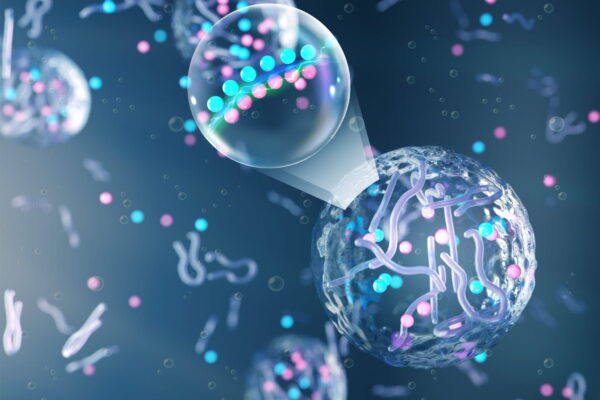

Much of cell behavior is governed by the actions of biomolecular condensates: building block molecules that glom together and scatter apart as needed. Biomolecular condensates constantly shift their phase, sometimes becoming solid, sometimes like little droplets of oil in vinegar, and other phases in between. Understanding the electrochemical properties of such slippery molecules has been a recent focus for researchers at Washington University in St. Louis.

In research published in Nature Chemistry, Yifan Dai, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering at the McKelvey School of Engineering, shares the rules involving the intracellular electrochemical properties that affect movement and chemical activities inside the cell and how that might afffect cell processes as a condensate ages. The research can inform development of treatments for diseases such as ALS or cancer.

Extracellular flow, or the movement of ions between cell membrane channels, is well studied, but little was known about those same electrochemical fields at play inside the cell.

“In the past century, people have learned a lot regarding electrochemical effects caused by extracellular environmental perturbances. However, in the intracellular world, we do not know much yet.” Dai said.

This work is one of the first steps to writing those rules, Dai and collaborators from Stanford University, including Guosong Hong and Richard N. Zare, show condensation and the non-equilibrium process after condensation is itself a way to regulate the electrochemical dynamics of the environments.

Read the full story on the McKelvey Engineering website.