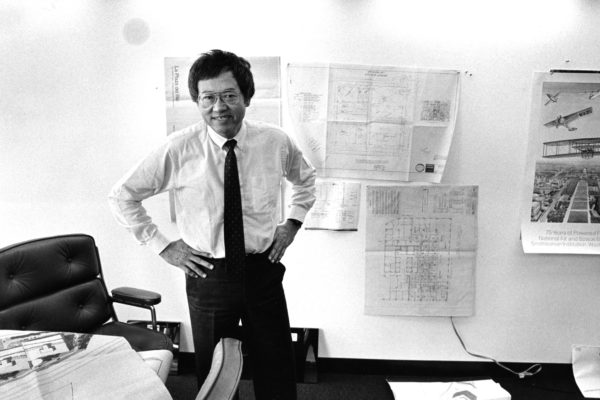

Rebecca Copeland, professor of Japanese language and literature in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, is a nationally known scholar of modern Japanese literature, a translator of contemporary Japanese novels, and, now, a novelist herself.

Copeland is author of “The Kimono Tattoo,” a mystery set in Kyoto that transports readers to famous temples, little-known alleys and even its zoo. The novel’s American protagonist, a failed academic working as a translator in Japan, is frustrated with her work and haunted by her past when she is given the offer to translate a new novel by a long-forgotten writer.

In this Q&A, Copeland talks about her new novel, her work as a translator and academic, and the way that the Western publishing industry orientalizes Japanese crime fiction.

What inspired you to write this novel?

I’ve always enjoyed mysteries that take you to other places. Sujata Massey’s Rei Shimura stories take us to Japan; Qiu Xiaolong’s Inspector Chen series to China. I found Nicole Mones’ “A Cup of Light” and Kazuo Ishiguro’s “When We Were Orphans,” both also set in China, mesmerizing for the way they open new landscapes with their writing and transport us across oceans and eras.

We travel, we learn and we sleuth as we read. I decided to try my hand at a mystery set in Kyoto. I started writing in 2012 during the summers and eventually I found my way to “The Kimono Tattoo.”

You also collect kimonos. What fascinates you about the kimono as a cultural object?

My personal experience with kimono goes back to my youth and my first lessons in Japanese dance. I had to wear kimono to every lesson, and the dance teacher required that I learn how to care for the garment, too. That’s how I learned to wear kimono. Is it strange to say “learned to wear”?

In “The Kimono Tattoo,” I try to dispel the misunderstanding of the kimono as confining. Even in Japan, and certainly abroad, people often think of the kimono as such a restrictive, formulaic garment. But it was standard wear for centuries in Japan, and men and women lived very happy active lives in kimono!

As I crafted scenes in the novel that involved kimono, I tried to give readers a sense of the garment’s richness. One’s choice of kimono signals a person’s status, gender, occupation and age. The way you wear your kimono, the knot of the obi sash, the looseness of the collar, the colors and fabrics you choose provide hints to your character and sense of taste.

You’re a frequent translator of Japanese fiction as well as a researcher and, now, novelist. What kinds of ideas are you able to explore in writing fiction that you can’t explore in your research?

Fiction allows me another way to present Japan to readers. Before writing “The Kimono Tattoo,” I experimented with a kind of hybrid approach to academic prose. For example, the introduction to “Diva Nation,” the anthology of essays I co-edited with Laura Miller, eschewed the usual outline/overview that you have with such a collection. Instead, we produced an impressionistic, almost dramatic recitation of the ways we have interacted with the diva throughout our careers. We achieved the same aims of introducing our topic, but in a much more active way.

How does writing a novel change your perspective on the work of translation?

It’s made a world of difference. I have a much stronger admiration for the authors I translate and the work they put into their fiction! I also feel even more in awe of successful translations. I find them very nearly magical.

When a translator strikes upon just the right word or phrase to transport the essence of a text from one linguistic system to another, it is a moment akin to pure alchemy — mysterious and inexplicable. I’ve found the same is true for creative writing. As I write, I see scenes play across the screen of my imagination — trying to reproduce that cinematic moment on paper is akin to translation.

You’ve written before about the tendency of promoters and publishers of Japanese novels in English to ‘orientalize’ their materials. Why is orientalization of Japanese fiction and authors so prevalent, and how does your writing combat those stereotypes?

Years ago, the author Kirino Natsuo, then known for her hard-boiled mysteries, complained to me about the cover art for her novel “OUT.” The Italian translation pictured a geisha-esque woman with white-painted face. But the novel featured middle-aged housewives who ran a clandestine body disposal operation! The cover had no connection with the story itself. It only aimed to trade on the cheesiest of stereotypes.

But this marketing scheme was not only visited on Kirino’s works. I began to notice that almost all book covers for translations of Japanese writers, particularly women writers, focused on the Asian female body. Many offered close-ups of the eye, and only the eye, in an oddly disfiguring way. Marketers clearly want to highlight the Asian-ness of the author, hoping to attract readership to the promise of something “exotic.” In the process, they use the female Asian body in a way that dehumanizes and sexualizes it at the same time. Even worse, the writer herself is often writing against this very kind of exploitation.

Plenty of covers capitalize on the kimono to suggest the seductive and tawdry. My novel describes a kimono that has a storied past, that may be haunted or cursed, but for the most part, the novel also presents the kimono as a wonderfully flexible, playful, accommodating garment of clothing that men and women wear regardless of age or nationality.

You have another book out as well, “Yamamba: In Search of the Japanese Mountain Witch.” What is that collection about? How does your fiction relate to your research?

The star of this collection is the yamamba, and it’s hard to find a figure more compelling. Both demon and god, she’s a female force akin to nature itself. Often translated as “mountain witch,” the yamamba is a notorious shapeshifter. You never quite know where she will turn up next or in what form. She’s monstrous and cannibalistic in some ancient stories, nurturing and protective in others. In the mid-20th century, the yamamba enjoyed yet another incarnation in the hands of Japanese women writers who reclaimed her as a feminist icon fearless in the face of all who would silence strong, independent, artistic women.

Our anthology draws on the yamamba as an inspirational figure, an instigator, you might say, for innovative art. Seeking to imagine yamamba encounters in the 21st century, my co-editor, Linda Ehrlich, and I brought together various artists, scholars and writers, and gave them free rein. As a result, the volume touches on mythology, Noh performances, avant-garde dance, graphic art, fiction and poetry. Each piece reveals a different viewpoint. Linda, for example, contributes a lyrical poem about the yamamba’s vastness, while I bring her to the North Carolina mountains in my short story “Blue Ridge Yamamba.”