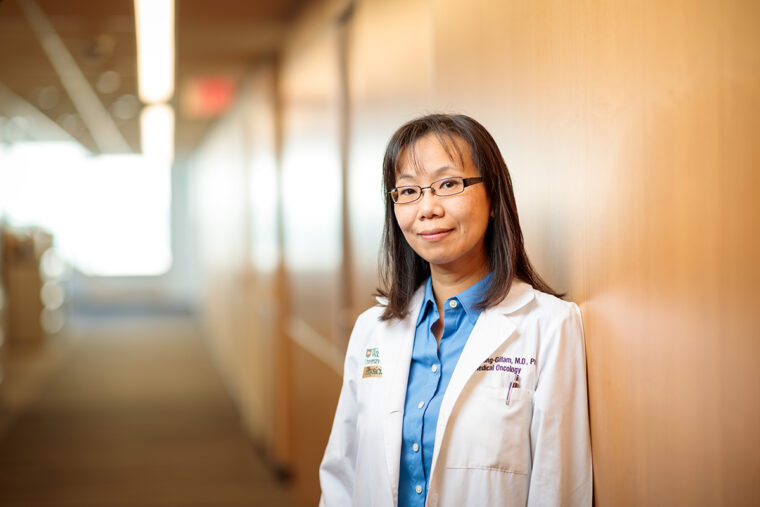

For Andrea Wang-Gillam, MD, PhD, it all started with a basket of eggs — just one example of the gifts patients would give to show their appreciation of her mother, an endocrinologist.

“At that time, we lived on the campus of a large hospital in China,” said Wang-Gillam, a gastrointestinal oncologist specializing in pancreatic cancer at Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. “My mother’s patients would come to our house with baskets of eggs or something to show their appreciation. You could see how thankful they were that she was able to help them.”

This sparked Wang-Gillam’s lifelong interest in helping people through medicine. Her parents and grandparents all practiced medicine in China: her father was a pathologist and a dean at a medical university; one of her grandmothers was an obstetrician/gynecologist; and one of her grandfathers was an internist. Further, living on a medical campus, she was immersed in the field.

When it came time to decide whether to go into a similar line of work, the decision was easy. In doing so, she quickly came to experience a sense of reward from helping people. That sense of reward is important in her area of expertise — pancreatic cancer is one of the deadliest types of cancer, with a one-year survival rate of 27% and a five-year survival rate of about 8%.

Wang-Gillam, an associate professor of medicine, works with researchers across the School of Medicine to try to improve such poor outcomes. “One of the great things about WashU is that all of the collaborators are extremely collegial. This is a devastating disease, and everybody is fairly humbled by it, so clinicians and researchers have a common goal: Everybody works so hard to try to improve the outcomes in patients.”

Though primarily a researcher, Wang-Gillam regularly interacts with patients in her clinical work and through clinical trials. “That patient contact inspires me to do more research,” she said. “The generosity of the patients also inspires me. Patients are very strong in such a stressful situation, and it’s inspiring to see how generous they are in participating in our research for the greater good.”

Wang-Gillam discussed her specialty, what drew her to it, and other aspects of her career and life:

What made you choose pancreatic cancer as your specialty?

It’s an area that really needs a lot of research. Survival hasn’t improved much over the last decade or so. There are limited therapeutic interventions or options for patients, and I feel patients really deserve more. Given my research background and my interest in drug development, I thought it would be a great area to go into. It’s a disease that desperately needs new drugs.

Why do you think this area is so in need of research?

There has been great science in terms of discovering and understanding the genomic background of pancreatic cancer, but this is a difficult cancer to study and treat for several reasons. One is that we discover the cancer at a very late stage because patients rarely have warning signs; the symptoms are pretty vague before people discover they have metastatic cancer. Half of patients with pancreatic cancer who present with symptoms already have stage 4 disease. Compare that to, for instance, breast cancer; people are screened via mammogram, and the majority of patients have early-stage cancer, which is curable. It’s similar with colon cancer.

The second reason it’s difficult to treat involves chemotherapy as part of standard care. Certain cancer cells reside in a tissue structure called stroma. Stroma is very fibrous, so there’s a theory that it’s difficult for any kind of chemotherapy or agent to diffuse into stroma. The stroma itself creates a physical barrier to drug delivery.

Is there currently no screening process for pancreatic cancer?

There is no screening right now. Close to 50,000 people a year are diagnosed with this cancer, which is a relatively small pool compared to other cancers. Because the incidence is low, we have to find a very precise screening tool; we don’t want to have a lot of false positives and create panic in patients. So we need a better strategy. Currently, the goal is to identify the high-risk groups and come up with a screening tool for them.

What does your research focus on?

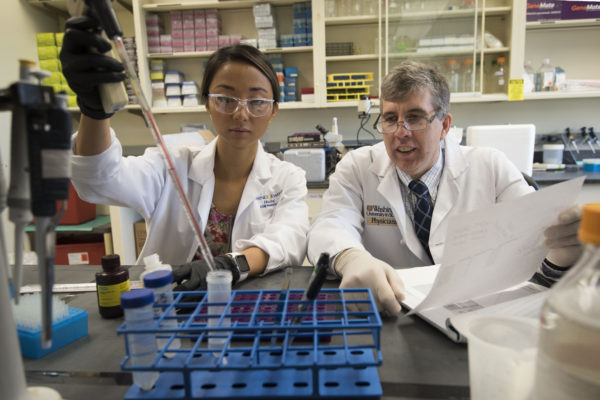

My research is focused on new drug development through translational research, which means I bring what has been discovered in the lab to a clinical setting via early-phase clinical trials. I work with lab scientists such as Dr. David DeNardo, who studies tumor microenvironment, which is the cellular structure in which the tumor resides. The microenvironment includes the stroma and tumor-associated macrophages, which are immunosuppressive cells. We believe the interaction between these noncancerous and cancerous cells plays an important role in a treatment’s effectiveness. Dr. DeNardo has done a lot of research on how to target and deplete these tumor-associated macrophages, in addition to how to disrupt the stroma to improve the effectiveness of treatment.

We work together by translating the lab findings into phase 1 clinical trials. During the trials, we also collect biomarkers from patients — bowel specimens and tumor biopsies, for example. Those biospecimens go back to the basic scientist’s lab for analysis to try to figure out what worked in some patients and why, what didn’t work, and how to improve it. I also work on clinical trials for drugs that deliver molecules to specific genes we target because we believe those genes may cause pancreas cancer.

You and some other noted researchers recently received prestigious Specialized Programs of Research Excellence (SPORE) grants from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Tell us about this and what it means for your research.

The pancreas SPORE grant, led by Dr. William Hawkins, was a really big deal for our institution; there are only three pancreas SPORE grant awardees in the U.S., and we’re one of them. It offers us a unique opportunity to do translational research, which has helped foster collaboration between basic researchers and clinicians. There are four main research projects that are part of SPORE, and each project has a translational component for clinical trials, so you can see a direct and rapid translation from basic research to the clinical setting. I think that’s a unique part of this program.

Do people who participate in clinical trials have better outcomes?

That’s a really good question. If you participate in the trials, you contribute to the science, and if the trial is positive, you might have a better outcome. Not all of the trials patients participate in turn out to provide a better treatment regimen, but here at WashU, people get standard care at the minimum, so their outcomes won’t be compromised and could potentially be better.

You mentioned a sense of reward in your field. Tell us about that and what motivates you.

When I was in medical school, it was extremely rewarding to be able to help people in positions where they couldn’t help themselves, knowing somehow I made a difference. When I started working toward my PhD, I had an added rewarding experience being able to help a larger patient population through more broad-based research. When you take care of a patient on a daily basis, you feel great when they respond to treatment and feel better, but when you do a clinical study, regardless of whether you see the patient daily or not, the things you do still help them tremendously, so the rewarding feeling is really amplified.

What is your life outside of work like?

My husband, Michael Gillam, a business owner, has been very supportive of my school and work over the last 20 years. We had them while I was in school: my first son in my second year of med school; my second son when I finished my PhD; and my daughter when I finished residency. Both of my boys are in college in California — one is studying music, and the other is studying film production — and my daughter is in high school.

Any chance patients show up at your house with baskets of eggs, as they did when you were growing up?

No, but one time I took my daughter to the mall, and we ran into a woman who was walking very quickly through the building. I realized she was a patient I hadn’t seen in a while because she had been cured of rectal cancer. I asked her why she was walking around the mall, and she said, “Don’t you remember that you told me to exercise 30 minutes a day, every day?” She’d been doing that every single day ever since, and she told my daughter how much she appreciated what I had done for her. And you know, daughters don’t always care what moms do, but that allowed her to see my work from a slightly different perspective. Now she might go into medicine. She’s thinking about it, she’s interested!