Anthony J. Azama is standing on the track in the southwest corner of historic Francis Field on the campus of Washington University in St. Louis on a stifling hot September night.

It’s a little before 8 p.m., and the John M. Schael Director of Athletics is watching the top Division III women’s soccer team in America play its neighbor just a few blocks down the road, Fontbonne University.

Azama already knows many of the students, even though he’s relatively new to the job. He cheers players on the field by name, and applauds loudly when the Bears score midway through the first half to make the game 2-0.

On this night, he is both fan and administrator, big brother and program boss. And it’s not only the women’s soccer team with whom he demonstrates this.

Just before halftime, with the lights starting to buzz and the sun setting, a couple of student-athletes emerge out of the shadows in the corner. Two men’s soccer players have been working out and are heading back to the Athletic Complex.

When they see Azama standing on the track, they wave, and yell, “Hey Anthony, you’ll have to come work out with us sometime.” He acknowledges them with a broad smile, then calls out as he pats his stomach, “I’m almost there! I’ve got a few more of these to lose first.”

James Byard/Washington University)

As they walk further away, he says, quietly, proudly, “Look at that. Those guys are working out on their own time — beyond practice. That’s how badly they want to win. That’s what kind of scholar-champions we have here. That’s why I love this place.”

It’s an admiration that’s already going both ways. What’s equally impressive about the exchange is the ease the players have with an administrator who has been on the job less than three months. They call out a “Hey Anthony!” to the man who runs their athletics program as if he were another student walking on campus, or someone they’d see on the weekend.

The students are clearly his priority: He already has met with each team individually. He has been to their games. He’s seen on campus. He has told his assistant that a student-athlete or a coach will never need an appointment to see him, and he has every home game, match or meet blocked out on his calendar.

The Washington University Athletics Program already is one of the top Division III programs in the country. But if anyone can take it to even greater heights, Azama can. Here are five reasons why:

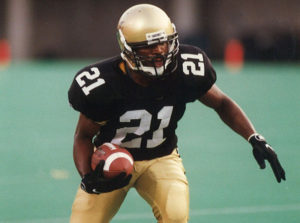

He played Division I football – but not like you think

Azama remembers the exact moment he first played in an NCAA football game: The fifth game of his freshman season, Oct. 8, 1994, at the University of Cincinnati’s Nippert Stadium. “I remember the moment my foot first crossed the white line, thinking, ‘this just got real.’”

Recruited to Vanderbilt University out of Daytona Beach Mainland High School, Azama knew what he had to do to succeed at a university known more for its academics than its athletics. “I had a competitive spirit and wanted to do well in the classroom to show that I belonged,” he said, “all the way down to sitting in the front row in the classroom and making sure I asked one to three questions every class, so the professor would know me by name.”

In his four years on the football field, 1994-97, he would play under three head coaches, and the experience would prove to be a bit of a roller-coaster ride. “I didn’t walk in being a star recruit,” he said. “I had to earn my keep. Then my position was taken away, and I had to earn it back.”

The experience, he said, taught him resiliency and perseverance.

“I had to figure out what each head coach wanted so I could still play in the program,” he said. “But it’s been no different in my professional career. I’ve had different bosses, a couple of different ADs.

“But it’s up to you to figure out that when there’s a new song playing, it’s time to dance to a different tune.”

It wasn’t just his playing experience that shaped him

At Vanderbilt, Azama got involved at a community center in Nashville that impressed him so much, he ended up recruiting teammates to work in the center twice a month, tutoring younger kids in math, or bringing clippers and offering haircuts.

“I knew I had teammates with so many different talents beyond football,” he said. “I just helped provide the vehicle to share them.” The experience, he said, was the first time he learned sports can transcend the field of play. “When you have someone who’s 6-4, 6-5, 300 pounds, sitting in a kindergarten chair and sharing a moment with a young person, that really changed my mentality as it pertained to the power of sports,” he said.

WashU is “about giving young people the championship habits that are bigger than just sports.”

Anthony Azama

Azama said it was a gift to see the game through a different lens — and it’s that same lens through which he views the student-athlete experience at Washington University. “Those of us who are lucky to have the ability to play a sport, I want us to be three-dimensional: To be leaders in the classroom; to be competitors in the sports that we love; and then to be engaged in the campus community, as well as in the surrounding community.”

Azama calls this “maximizing the moment” and it’s why he believes the student-athlete experience is one of the best internships available. It’s also why he considers every sport under his tutelage equally important. “I tell people, ‘You don’t have to know anything about the sport, or be in love with it,” he said. “But get to know our kids and you’ll fall in love with them.”

His role models may surprise you

When asked who has influenced him in his life, he cites his mom, of course, as well as Duke Athletic Director Kevin White, who he said gave him some valuable advice when he was looking to make the jump years ago from sports marketing to higher education.

But the person who has had a driving influence? Shirley Chisholm, the first African-American woman elected to Congress, and the woman who said, “You don’t make progress by standing on the sidelines, whimpering and complaining. You make progress by implementing ideas.”

Azama remembers writing a book report on her as a third-grade elementary student in Daytona Beach, Fla., and then having the opportunity to meet and get a picture with her as a senior honors student during her visit to his high school. It’s a photo he has kept his entire life.

“Her story inspired me because she had a desire that tied into her purpose, and she was not going to be denied,” Azama said. “That in and of itself is inspirational. Coming out of Daytona Beach, a lot of people said, ‘What do you mean you’re going to go play Division I football? You’re 155 pounds!’ There were more negative comments like that than positive.”

He smiles: “So I just learned to lean back on her biography.”

He has a plan — and it’s not just about winning

There’s no denying this athletics director wants the program to win. “As someone who enjoys sports and appreciates the power of sports, sometimes you need to swing for the fences,” Azama said. But he’s also intent on instilling balance.

“You have young people excited about the season who feel as if they can go undefeated,” he said. “It’s up to administrators to be the consistent support throughout the season so you achieve balance where they inspire us and we inspire them.”

He’ll do his part, and he has a vision for the athletics program as a whole, something he’s calling a “Center of Excellence,” that will incorporate the best in sports medicine, nutrition, strength and conditioning and sports psychology and will support each student-athlete and enhance their experience.

He’d also like to see a wall of champions in the Athletic Complex lobby with plaques marking all the national titles, “plus an empty space for the next one to inspire and recruit,” he said. But he also envisions in the same space a wall of corporations/companies that have hired Washington University graduates. “That is quintessentially what WashU is about,” he said. “We’re about giving young people the championship habits that are bigger than just sports.”

He’s one happy man

His enthusiasm is infectious. “I’m usually walking up the steps to my office about 6:15 a.m.,” he said. “I try to get a workout in because to me that’s the most important meeting that I have. If I’m at my best, then I’m giving my best to coaches and student-athletes.

“Every day, I ask myself the same question I’ve asked myself since 10th grade: ‘How bad do I want to be great? And how much of a positive influence do I want to be to others?’

“In this business, there is no cruise control,” he said. “I just want to have more energy and more enthusiasm than most people I run into.”