On a sunny day in late March, Bradley Schlaggar, MD, PhD, prepared to coach his son’s hockey team through its first practice of the season.

It would be the first time 11-year-old Simeon would be back on the ice since being declared in remission from leukemia.

“There’s a look you see in the eyes of parents of very sick kids,” said Schlaggar, who works as a pediatric neurologist at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis when not coaching hockey. “I understand that look in their eyes much more deeply now. There’s a lot of trauma that comes with seeing your child really, gravely ill.”

That empathy was hard-won. Simeon was diagnosed a year ago, sending the whole family into a months-long nightmare of chemotherapy and tests and endless days and nights in the hospital. Since December, though, Simeon has been on maintenance chemotherapy, and life is beginning to return to normal.

It was a tough time for a family that already has had more than its share of medical challenges. Schlaggar lost his sister to cancer in 1998, just shy of her 36th birthday. His father died in 2004, also from cancer. In 2012, he underwent urgent surgery and narrowly avoided a major heart attack at age 48. His wife, Christina Lessov-Schlaggar, PhD, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the School of Medicine, was diagnosed with breast cancer just two weeks later. She is now in remission.

“Each of these terrible experiences has taught me something about medicine and the medical system and what it means to be a doctor,” said Schlaggar, the A. Ernest and Jane G. Stein Professor of Neurology and director of the Division of Pediatric and Developmental Neurology. “But nothing, nothing really comes close to what it’s like when it’s your own child.”

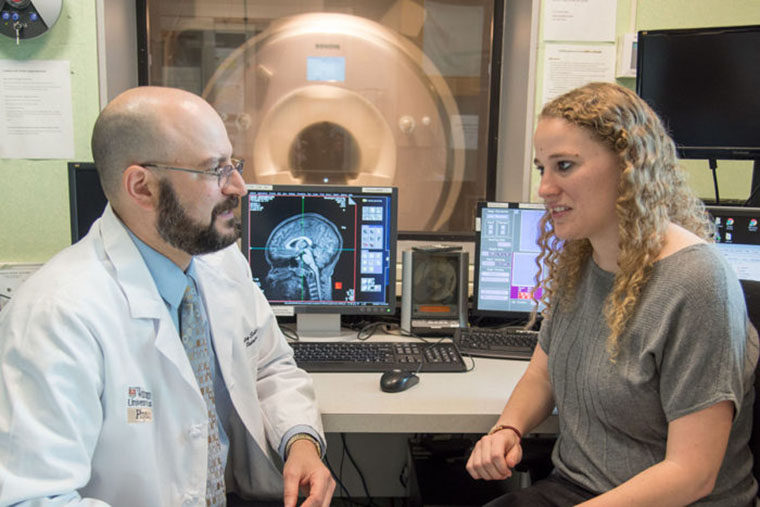

With Simeon back in school and the latest family health crisis easing, Schlaggar, who is also a professor of radiology, of psychiatry, of pediatrics and of neuroscience, has been able to turn his attention back to what he does best: studying how the brain develops, and how and why the patterns of normal development sometimes go awry.

Read the full profile on the School of Medicine site.