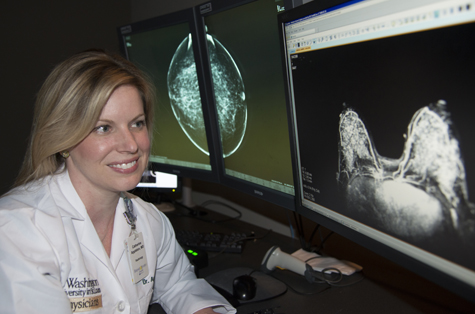

Catherine “Kate” Appleton, MD, is assistant professor of radiology and chief of breast imaging at the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology. Last year, she and her colleagues evaluated and cared for more than 30,000 women who came to the Joanne Knight Breast Health Center for screening, diagnostic evaluation and image-guided breast procedures.

You received your medical degree with research honors from the University of Florida in 2000. What motivated you to study medicine?

My mom is a nurse, and growing up I was always impressed with her ability to care for us. She always knew what to do to make me feel better. Early on, I had a strong interest in science, and I blended that with what I saw my mom doing – caring for people. She very much encouraged me to pursue my interest in science, and that led to a career in medicine.

Last year, you were appointed chief of breast imaging and director of the breast radiology service at age 36. What advice would you offer others pursuing an accelerated career path in medicine?

I started medical school when I was 20, as part of a seven-year combined undergraduate/medical school program at the University of Florida, so I was accelerated on the front end. I think whether you’re on a traditional track, a fast track or your own track, it’s important to talk with and spend time with physicians. As early as high school, I shadowed physicians and volunteered at our local hospital. I asked questions. Those things helped me solidify my interests early on, so that I could make a decision to enter an accelerated program. Exposure to the various fields within medicine is important so you can appreciate the diverse opportunities medicine affords. My career as a breast-imaging radiologist is very different than many other medical specialties, in terms of my day-to-day work. I think doing your homework and putting in the time is really important.

Were you interested in other types of medicine, or did you always know you would be doing what you are now?

Entering medical school, I was actually really interested in forensic pathology. However, during my clinical rotations, I quickly decided I wanted to interact with patients and their families. I was a medical student who loved almost every rotation; the great thing about radiology was that you interfaced with physicians across the board. That aspect sparked my initial interest in radiology. Then, in my radiology residency here at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine, I rotated through breast imaging. Unlike some parts of radiology in which you can be a step or two removed from patient care, there is patient interaction on a daily basis in breast imaging. I had missed that and felt this was a good fit for me. And, of course, meeting Dr. Barbara Monsees, who is my mentor and the former chief of breast imaging, really helped solidify that this is what I was meant to do.

What sort of mentoring are you a part of?

I mentor our residents and fellows formally and informally. I’ve had medical school and undergraduate students approach me, and I do my best to mentor them on an individual basis, as well. And I still consider myself a mentee, so I continue to be mentored by some very generous people in the medical center and across the country.

What other details can you share about being a mentee?

Certainly, this transition into chief of breast imaging was monumental for me. I sought out the advice and counsel of other leaders in the department and medical school, as well as contacts I have across the country. I thought it would be valuable to learn from their experiences — where they think they took a positive step or where they wish they would have done something differently.

Have you found that being a mentee helps you be a better mentor?

Absolutely. I think once you have been mentored by multiple people, you can distill what advice was more salient. I think as a mentor you need to look at individual mentees, and their big picture, because your personal anecdotes are one thing, but working within a system will have different implications for different people. One size doesn’t fit all.

What do you find most challenging about your job?

The most challenging thing is to tell a very young patient that she has breast cancer. Young patients in their 20s and early 30s are more often blindsided by the diagnosis, and it’s very difficult. But what might surprise people is that more often than not, we actually give good news here. Most people who walk through the door leave with good news.

What research projects are you working on?

One of the awesome things about being at Washington University is the tremendous potential for collaboration, and I’ve taken advantage of that potential. I’m working with professors Lihong Wang and Mark Anastasio in the School of Engineering & Applied Science on some very exciting projects. I bring the clinical perspective, and they bring the technical development and expertise, so it’s fantastic translational research. The project with Professor Wang involves photoacoustic imaging of sentinel lymph nodes in breast cancer patients. In addition, in the breast center, I collaborate with multiple colleagues, including Dr. Julie Margenthaler and my fellow breast imagers. Our section is completing some novel projects involving breast tomosynthesis, the so-called “3-D mammogram.”

Regarding my personal projects, I am currently working on an analysis of decision fatigue in mammography interpretation. After an article was published about judicial decision fatigue some time ago, I started wondering, “Do I do a better job of reading a mammogram early in the day, before lunch, after lunch or late in the day?” So I’m looking at our decisiveness in mammography interpretation, based on the time of day. I want to see if there’s a tipping point where you reach decision fatigue.

What should everyone know about breast cancer?

Women should get a mammogram once per year starting at age 40 if they are at average risk for breast cancer. But guidelines change, so it’s important to stay current and speak to your health-care provider, or call us, and we can advise patients on what they need to do. High-risk patients, including those with a family history, should be assertive about getting the care they need. Treatments continue to improve, outcomes continue to improve, but early diagnosis is key. Get your mammogram.

Almost everyone has been affected by cancer. Outside of your medical practice, how have you been affected?

Like many people, I’ve had family members affected by cancer including, most recently, someone diagnosed with breast cancer. There are so many chronic illnesses that people face, and I think whether it’s cancer or another disease, a physician’s personal and family experiences foster empathy for patients that translate across multiple ailments. For me, those experiences have definitely made me a more sympathetic and more empathetic physician.

How so?

It’s tough to be a patient. It’s tough not to know what happens next – it’s frightening. So I always have in mind, as I’m telling a patient bad news on, potentially, the worst day of her life, she will probably remember exactly what I say for the rest of her life. I want to get it right, say the right thing in the right way. Being a patient and being the family member of a patient, myself, has made me a better listener. Being a parent has also made me a better listener.

Talk about your children and how they’ve affected how you practice medicine.

Lily is 8, and Mack is 6. I think any parent knows that it’s the most difficult job in the world, but it’s also the very best and most rewarding. My children, more than anything, have taught me patience, and that translates to being a better listener, slowing down and taking greater care and time with patients.

How difficult is it balancing your professional and personal responsibilities?

It’s always a juggle. My children know that I take my job very seriously, and I think it’s important that I model that for them. They know that when I go to work, I take care of people, and they are proud of that, I think. However, I believe at the end of the day Lily and Mack know they are my very first priority. And we also have very interesting dinner conversation! My children know a lot about what I do; it’s just part of the fabric of our home life. I spend as much of my free time with my children as I can, and they know they’re No. 1.

What are some favorite family activities that help you recharge?

We love to be outside in our yard, play ball with the kids or go on the swing set. We have two big dogs to play with. And, we actually just got two chickens. I love animals, so that’s been a fun turn of events.

Tell us more about the chickens. Did your children ask for them?

Oh no, that was my crazy idea. My husband is a great sport. After almost a year, I finally wore him down, and right after Easter we got two chickens. It’s been an interesting education in poultry.

I have an organic garden, and I just thought that they dovetailed very nicely with my garden. The kids are learning a lot about where their food comes from, and it’s just an interesting and fun family activity.

Any other hobbies?

I have accumulated them throughout my life. The piano is a holdover from my childhood, and I wanted music to be a part of my kids’ lives. And I like to be active, so having pets and a garden and doing sports are all things to keep my children and me active and engaged. We ice skate together. I play tennis, terribly, but I have fun. I’m not sure I would exactly ascribe to the “work-hard, play-hard” philosophy, but I do think life is made to be enjoyed, and so I’m trying out different things. I took a knitting class last fall because I thought, “I’ll try that,” but it wasn’t for me.

Tell us more about your chicken-averse husband.

His name is Taka Yanagimoto, and he is the photography coordinator for the Cardinals, and he’s awesome. He’s fun, and he makes me laugh all the time. And like I said, he’s a good sport. Anybody who lets me get two chickens is a good sport.