David Kilper

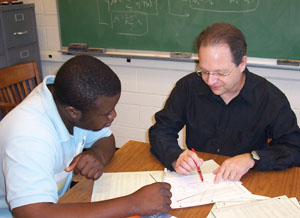

Tom Bernatowicz, PhD (right), professor of physics in Arts & Sciences, and David Vera-Vazquez, a junior majoring in biology in Arts & Sciences, apply the right-hand rule to a “two-minute problem” about the forces that would be generated if electric current were flowing through two perpendicular wires. Both have the fingers of their right hands curled in the direction of the magnetic field in one of the wires. The question is: What happens to the index finger and the thumb? The two-minute problems, which require conceptual understanding but not math, are one of the features of Bernatowicz’s innovative introductory course in physics.

Tom Bernatowicz, PhD, professor of physics in Arts & Sciences, is an enthusiast by nature. Whatever he chooses to do — whether it is cooking, research, teaching or learning a language — he does con amore and with passion.

His first enthusiasm was crystallography, which attracted his attention in the fourth grade.

“When I saw an amethyst crystal and got to handle it,” he says “it was like an explosion went off in my head. Its regularity implied the atoms had arranged themselves in an ordered way, and the fact that this could happen naturally, seemed to me, marvelous.”

Besides mineralogy, the only other subject that ever tempted Bernatowicz was astrophysics.

“When I started getting interested in astronomy,” he says, “I felt really guilty about being disloyal to mineralogy. Isn’t that weird?”

Real stardust doesn’t sparkle

At Washington University, Bernatowicz has been able to stay true to both loves. In the mid 1980s, he was swept up in the study of tiny crystals, called stardust grains. These formed around stars outside the Earth’s solar system, became part of the mix of dust and gas that gave rise to the Sun and planets, were carried to Earth inside meteorites, boiled out of those meteorites in hot acid baths in Chicago, and then shipped to his laboratory on the fourth floor of Compton Hall.

Ask him for the high point of his research career, and he says, “That’s easy. You’re sitting across the table from the first person to lay eyes on solid material from outside our own solar system.”

In the 1970s, he says, scientists began finding isotopic anomalies in the noble gases neon and xenon in primitive meteorites, meteorites that had not been heated above room temperature in the giant rock polisher of the asteroid belt since the formation of the solar system.

By analyzing the isotopic compositions of several elements, scientists are able to glean clues about the origin of stardust grains in the atmospheres of dying red giant stars or in exploding supernovae.

When a doctoral student heated a primitive meteorite in 1972 and it gave off pure neon-22, scientists were stunned. No known solar system process would produce this isotope without its sister isotopes neon-20 and neon-21. Gradually, they came to suspect that some part of the meteorite had come from outside of the solar system.

But which part? To find out, a group at the University of Chicago starting dissolving meteorites in strong acids — a process their leader Edward Anders, PhD, characterized as “burning down the haystack to find the needle.”

In 1987, the neon-22-enriched material left after they dissolved most of a primitive meteorite that fell on Murray, Ky., in 1950, was shipped to WUSTL, where Ernst Zinner, PhD, research professor of physics, had pioneered the development of techniques to make isotopic measurements on small grains.

When Bernatowicz looked at one of these grains under a transmission electron microscope, he thought, “I’m the first human being to actually see a piece of material that’s from outside our solar system — not only that, but material that was made before there was a solar system. The hair on the back of my neck stood up. I’ll never forget it.”

This work, which Bernatowicz likes to call “doing astronomy with a microscope instead of a telescope,” earned the Washington University group the cover of the December 31, 1987, issue of Nature, and two articles and a commentary inside.

Bernatowicz had mixed feelings about his 15 minutes of fame. He says no newspaper got the story right. Even in Science News, his “stardust” appeared as “celestial sandpaper,” which isn’t wrong, exactly, but just sort of misses the wonder of it all.

Who was Kiki of Montparnasse?

Zinner and Bernatowicz continue to probe the secrets of stardust, but lately they’ve also been conducting a running contest to see who knows more about Paris. Bernatowicz first visited Paris in 1998 for a symposium to celebrate the work of his friend, the late Paul Pellas, a colorful French scientist who in a former career as a movie actor had the distinction of being slapped by Brigitte Bardot.

“He fell in love with Paris immediately,” Zinner says, and became an expert on all things Paris.

“You can’t find anything he doesn’t know, even though he’s only been to Paris a few times, and I’ve been many.”

“Do you know who Kiki of Montparnasse was?” Zinner asks, testing Bernatowicz.

But Bernatowicz responds that, of course, Kiki was Man Ray’s girlfriend and the subject of a famous photograph in the manner of Ingres’ Valpincon Bather, to which Ray added f-holes like those in a violin.

Teaching a love of physics

Bernatowicz (right) works with Wali Akande, PhD, a student from Nigeria who earned a bachelor’s degree in engineering at WUSTL and recently earned a doctorate from Princeton University. “Akande was a fantastic guy,” Bernatowicz says. “He worked with me on the formation of mineral grains around old red giant stars, and we wrote a paper together that appeared in the Astrophysical Journal.“

So there is stardust and Paris, languages and cooking, but there is also — these days especially — teaching. Since 2004, Bernatowicz’s simple but audacious ambition is to teach a rigorous introductory physics class that makes students love physics.

Tony Biondo, senior machinist in the physics department, says he never has known anyone more dedicated to his work than Bernatowicz — and Biondo has worked at WUSTL 36 years.

“Tom never lost sight of the fact that teaching is our prime imperative,” Biondo says.

As a younger faculty member, Bernatowicz became dissatisfied with the traditional introductory physics course. He looked at the students and could tell most weren’t really following, and it left him unhappy.

“We physicists love physics,” he says, “and we want our students to love it, too. We’re not saying we’ll make it easy just so that they will love it, but that we want them to understand because it’s something we ourselves cherish and we want them to see how great it is.”

So he did research. He looked at other courses. He talked to people at conferences. In the end, he picked a course designed by Thomas A. Moore, PhD, of Pomona College and set forth in Moore’s textbook Six Ideas That Shaped Physics.

What impressed Bernatowicz about Moore’s approach was that Moore ran experiments in the classroom and altered his teaching practice according to the results. In other words, he was a good scientist inside the classroom as well as out of it.

Students in the new Six Ideas course, Bernatowicz says, “have to learn to think about the problem, what’s important, what’s not, what they know, what they need to know, whether they can sketch the situation, and how they can convert a sketch to mathematical terms — in other words, to think for themselves.” (For more about the course see “Physics according to Bernatowicz.”)

Bernatowicz taught the first section of the new course in 2004 to 62 students. This year, there are three sections of the course, each with roughly 120 students. Next year, there will be five sections. You could say Six Ideas has taken the university by storm.

“Came into the class hating physics,” one student wrote on ratemyprofessors.com, “and left enjoying it. His passion for the subject is obvious/contagious.”

In 2009, Bernatowicz won the inaugural David Hadas Teaching Award, which recognizes an outstanding tenured faculty member in Arts & Sciences who demonstrates commitment and excellence in teaching first-year undergraduates. The award was established in the memory of David Hadas, PhD, an English professor known for his warm personality and Socratic teaching style.

Bernatowicz was nominated for the award by Kenneth F. Kelton, PhD, the Arthur Holly Compton Professor in Arts & Sciences and chair of the physics department. In his nomination letter, Kelton called Bernatowicz “the most popular teacher in our introductory physics course that I have seen in the 24 years that I have been on the faculty of Washington University, almost always receiving standing ovations on the last day of class.”

“He is leading the department in the direction of teaching introductory physics in a more interactive, engaging manner,” says Martin Israel, PhD, professor of physics, one of four faculty members who will join Bernatowicz in teaching Six Ideas next fall.

Fast facts about Tom Bernatowicz

Languages studied: German, Russian, Classical Greek (both Homeric and Attic) and French

Favorite writers: Bertrand Russell, Euripides, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Franz Kafka, John Keats, Thomas Hardy, Edgar Allan Poe, H.G. Wells, Michel de Montaigne, Marcel Proust and Georges Simenon

Favorite physics quote: “That’s not right. That’s not even wrong.” -Wolfgang Pauli

Favorite cuisine: Indian, for which he grinds his own spices