After a person survives a heart attack, the heart has a brief window of time in which it can heal if the right circumstances exist. But most of the time, scar tissue forms in the areas that lacked oxygen during the heart attack. This scar tissue impairs heart function, which can worsen into heart failure, reducing quality of life and increasing the risk of early death.

A new study led by Sumanth D. Prabhu, MD, the Tobias and Hortense Lewin Distinguished Professor of Cardiovascular Diseases and director of the Cardiovascular Division at WashU Medicine, and Mohamed Ameen Ismahil, PhD, an assistant professor in the Cardiovascular Division, has identified a surprising role for the spleen — a small organ near the ribs that filters blood and fights infections — in helping the heart heal after a heart attack.

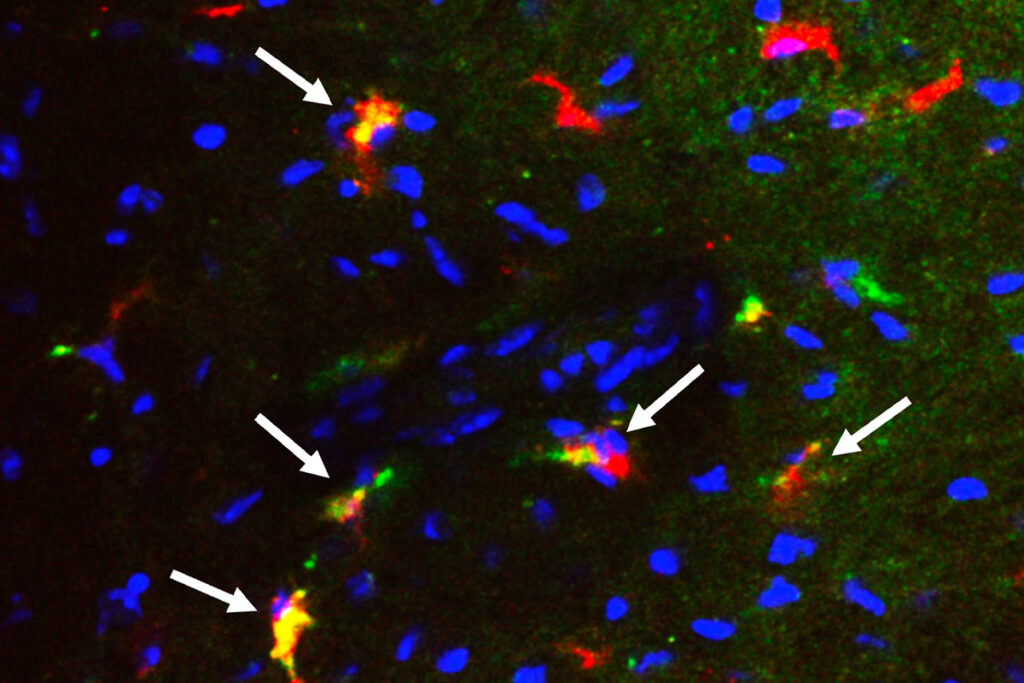

The research, published in Circulation, demonstrated in mice that specific immune cells called marginal metallophilic macrophages, which originate in the spleen, travel from the spleen to the heart and support a healing response after a heart attack.

Using mouse models, single-cell RNA sequencing and other advanced techniques, the researchers established that these specialized macrophages from the spleen help clear damaging immune cells, suppress inflammation and activate genes that help repair the injured cardiac tissue following a heart attack. To assess whether the same thing occurs in humans, the researchers measured levels of marginal metallophilic macrophages in blood samples collected from people upon their hospital admission due to a heart attack. The researchers compared these levels with those of cardiac patients who had coronary artery disease but had not recently had a heart attack. Prabhu and his colleagues found that levels of the specialized macrophages were higher in patients who had just had a heart attack.

The researchers also demonstrated that they could boost the numbers of these specialized immune cells in mice with an experimental drug, and that doing so improved the healing and anti-inflammatory effects. This medical intervention is not yet in clinical trials, but it suggests a possible future cardiac immunotherapy targeting the spleen to prevent heart failure in patients who survive a heart attack, which applies to hundreds of thousands of people in the U.S. each year.