Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have uncovered why some patients with a rare genetic disorder called primary ciliary dyskinesia have worse lung problems than others with the same disorder. The discovery, published in Science Translational Medicine, suggests that gene therapy to restore a missing protein complex could help treat the disease. Patients with the disorder who are treated at WashU Medicine participated in this research.

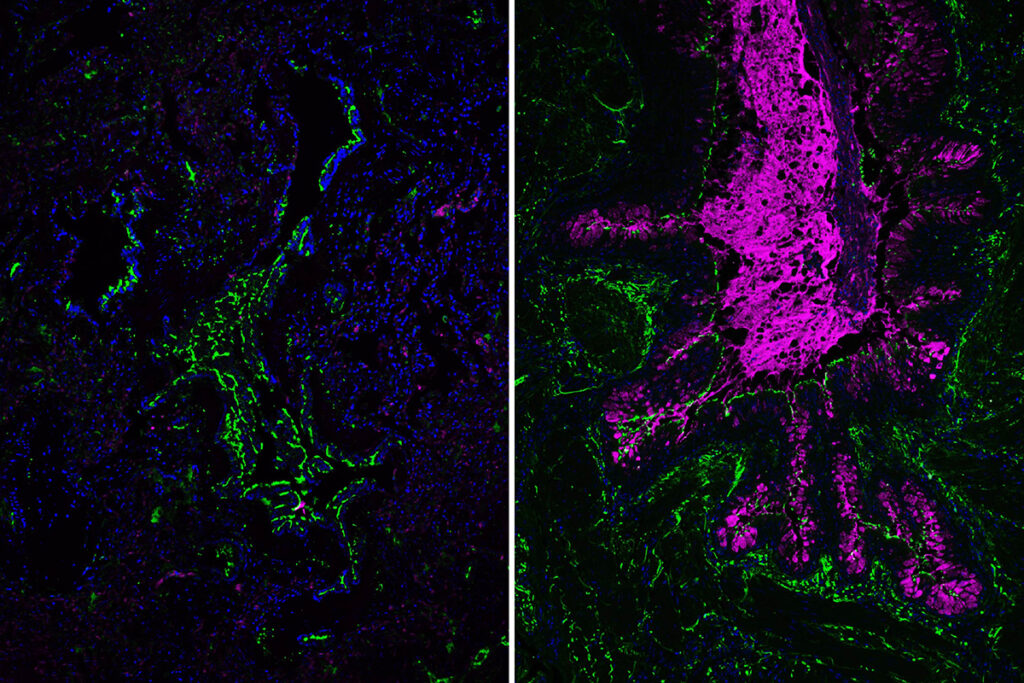

Primary ciliary dyskinesia is a rare genetic syndrome that causes defects in fine hair-like structures called cilia that line airways and other organs. The condition can cause respiratory disease, infertility and problems in the left-right orientation of organs in the body, such as when the heart is located on the right side of the chest rather than the left. More than 50 genes have been implicated in the disorder. For unknown reasons, variants in two genes that encode proteins called CCDC39 and CCDC40 cause more severe lung disease.

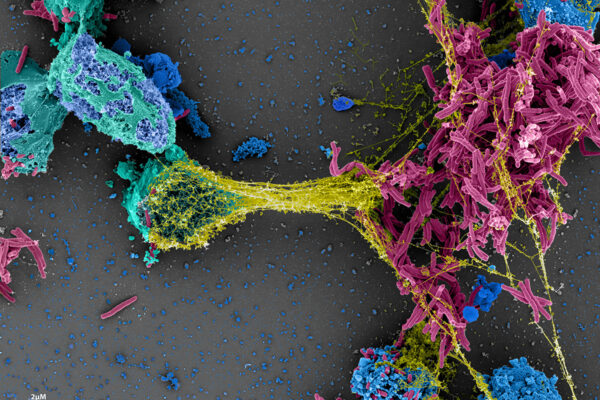

A research team, led by Susan K. Dutcher, PhD, a professor of genetics, and Steven L. Brody, MD, the Dorothy R. and Hubert C. Moog Professor of Pulmonary Medicine, found that these proteins come together to form a single scaffold to support the assembly of an extensive network of ciliary proteins. Beyond a dysfunctional ciliary network, the missing structure also leads some cells that should have cilia to instead produce mucus, which could account for the increased airway problems.

The investigators showed they could fix these defects in airway cells by delivering a normal version of the CCDC39 gene via a viral delivery system, demonstrating that a gene therapy approach could help these patients in the future.