Philip Skemer, associate department chair and professor of earth and planetary sciences, and graduate student Charis Horn, both in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, have published a study in Geophysical Research Letters that showcases the power and potential of the large volume torsion (LVT) apparatus.

This WashU-built device can squeeze and twist rocks with 100 tons of force and temperatures of 1,300 degrees Celsius (2,500 degrees Fahrenheit). “There are no other devices with the same capabilities anywhere else on the planet,” Skemer said.

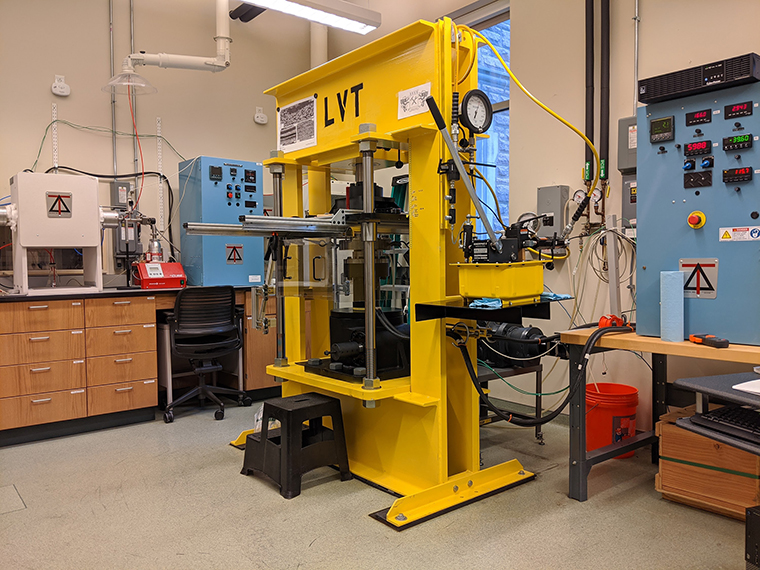

Skemer’s lab now has two LVT devices, built with support from the National Science Foundation, each standing 8 feet tall and weighing about 5,000 pounds. The LVTs were designed to experimentally reproduce how rocks deform in parts of the Earth that are subject to high pressure and temperature, including deep within faults where tectonic plates meet.

In the latest study, Horn and Skemer used the device to test talc, an extremely soft mineral that is commonly found in active, earthquake-prone faults.

Experiments with the LVTs showed an unexpected result: When pressed hard enough, the layers in the mineral form ripples, much like rumpled carpet. Those ripples create small pockets of empty space called ripplocations, features that were unknown to scientists a decade ago. “We’re pushing on the talc from all sides with an enormous amount of force,” Skemer said. “You would not expect that to create a void.”

Read more from The Ampersand.