Robert Boston

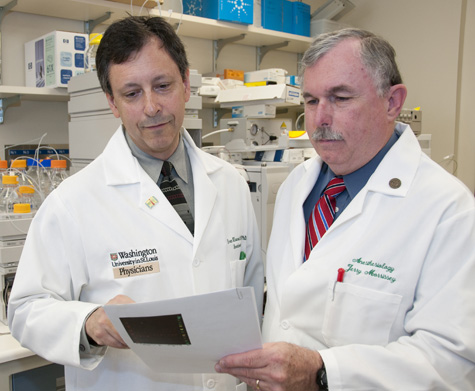

Evan Kharasch, MD, PhD (left), and Jerry Morrissey, PhD, in the lab where they discovered that two key proteins are elevated in the urine of patients with the most common forms of kidney cancer, and the findings may be used to develop a screening test for the early diagnosis of kidney cancer. “The university has benefited from Evan’s impressive progress in assisting research throughout both campuses,” says Provost Edward S. Macias, PhD, executive vice chancellor and the Barbara and David Thomas Distinguished Professor in Arts & Sciences. “His own successes in the laboratory and his very broad view of research have prepared him well.”

It’s not uncommon at Washington University School of Medicine to meet an investigator who has been running a laboratory for many years, but it is somewhat unusual to meet one who began running his first laboratory during high school.

“They turned a classroom into an independent study science lab,” says Evan D. Kharasch, MD, PhD. “I used part of that lab and conducted my own biochemistry and other experiments — something that never would happen today.”

Kharasch has been involved in scientific research ever since. An anesthesiologist by training, he is the Russell D. and Mary B. Shelden Professor of Anesthesiology and professor of biochemistry and molecular biophysics. Last spring, he also was appointed vice chancellor for research.

Applying science

He wanted to work in science from the time he was very young. With medicine, he found a way to apply it in daily life.

“I grew up in the era of the space program,” he says. “There wasn’t a launch or landing that I didn’t watch on a grainy, black-and-white television when I was a kid in Chicago.”

Kharasch attended Northwestern University, but he took a somewhat unorthodox path. As part of an honors program, he worked toward a combined bachelor’s-medical degree but soon decided to squeeze in a doctorate in pharmacology.

“Luckily, I was allowed to do two years of medical school and then three years of graduate school before I went back to finish medical school,” he says.

Later, he interrupted his anesthesiology residency, in Seattle at the University of Washington, to take a year off for research. His primary research interests as a new assistant professor were drug metabolism and pharmacology. Most of the university’s experts were in the pharmacy school rather than the medical school, so he arranged for a mini-postdoctoral fellowship with a pharmacy school faculty member.

“On my first day, he put his arm around me and said, ‘You’re a smart guy. You can do it,’” Kharasch says. “He just gave me a bench in his lab and said, ‘Go to it!’ So I did.”

Since then, Kharasch’s research has advanced in what he calls an “organic” way. His career path makes sense in hindsight, but he wouldn’t have predicted it. He still tells scientists in his laboratory to go where the science leads them. That’s how his career advanced.

For example, one day, a colleague in pharmacy suggested a joint experiment on the metabolism of a volatile anesthetic — a gas that is used during surgery to induce general anesthesia — and that conversation led to a 20-year collaboration. Kharasch concentrated on the effects of the anesthetic sevoflurane on the kidney. When the drug went to the FDA for approval, much of Kharasch’s research ended up in the safety package the FDA reviewed and used to approve it. The research also fundamentally changed how anesthesiologists think about how anesthetics might damage the kidney.

He also studied opioid drugs, and, as his research evolved, he focused on different ways individuals responded to the pain-killing medications as well as to anesthetic drugs. While still in Seattle, he also did research on drug interactions involving opioids and anesthetics.

And that work continues. Not long ago in studies of methadone, Kharasch found that some of what was written in the FDA safety package wasn’t correct and that the body processes the drug differently than previously believed. That made it difficult for physicians to understand how and when methadone is cleared from the body and may have been responsible for unintentional under- or overdosing, inadequate pain relief and various side effects.

“The goal is always to apply scientific principles to clinical practice,” he says. “We go from bedside to bench and then take our research findings back to patients. It turns out we were doing ‘translational medicine’ before it was in vogue.”

Translating science to administration

During his tenure in Seattle, Kharasch rose from assistant professor all the way to assistant dean for clinical research, the post he held when he decided to relocate to Washington University’s Department of Anesthesiology in 2005 where he directed clinical and translational research.

“Evan and I have been friends for years, and I have long believed his work epitomizes what clinical research should be,” says Alex S. Evers, MD, the Henry E. Mallinckrodt Professor and head of the Department of Anesthesiology. “I waited a long time for the opportunity to recruit Evan to Washington University, and it was worth the wait.”

Kharasch says regular movement between clinic and laboratory has taken him to surprising places. For example, the work he did with sevoflurane and the kidney led him to look at the issue of kidney toxicity, and a series of kidney function studies followed. Eventually, he began looking for biomarkers of kidney function, which culminated in a search for biomarkers of kidney cancer. Last spring, his research team published the first study to identify a kidney cancer biomarker in urine. The findings could be important in diagnosing kidney cancer, which normally is discovered only as an incidental finding when a person is tested for a different complaint.

Those kidney studies led him into another rapidly growing area of science: technology transfer. His laboratory has filed a patent on the kidney biomarker. Now a second round of clinical studies is under way to replicate the original findings and develop a test that could be commercialized. Meanwhile, the university’s Office of Technology Management seeks licensing partners to help get the findings into clinical use.

Research administration

Kharasch’s organic career path eventually led him into research administration.

“It grew,” he says, “out of the perspective of a faculty member who wanted to improve the system, and I enjoy working at the interface of policy, process, operations and strategic planning and being an advocate for the research enterprise and for the faculty, both individually and collectively.”

He sees a number of opportunities for growth, especially in the areas of innovation, entrepreneurialism, technology transfer and commercialization.

“The university has benefited from Evan’s impressive progress in assisting research throughout both campuses,” says Provost Edward S. Macias, PhD, executive vice chancellor and the Barbara and David Thomas Distinguished Professor in Arts & Sciences. “His own successes in the laboratory and his very broad view of research have prepared him well.”

Kharasch says many skills he uses running a laboratory can be adapted to overseeing the research enterprise.

“I get to work with incredibly smart and creative people,” Kharasch says. “One thing we’re focused on is getting groups of people to work together on projects and in new ways, linking individuals who might not otherwise have been natural collaborators. It’s crossing schools. It’s crossing disciplines. It’s crossing Forest Park.”

Like riding a bicycle

Courtesy photo

Evan and Karen Kharasch

A former percussionist, Kharasch gave up music because other interests limited his practice time, but he and his wife, Karen, still frequently enjoy the symphony and the opera.

They’re also avid skiers, but he admits skiing is a bit harder to do in Missouri than in Washington state.

“We’re also avid fans of minor league baseball,” he says. “During the summer, we spend many Friday nights across the river watching the Gateway Grizzlies. And I usually spend weekend mornings riding my bicycle. I’m not an expert cyclist, but I do enjoy a long morning’s ride with friends.”

Fast facts about Evan D. Kharasch

Born: August 6, 1957, in Chicago

Education: BS, medical science, 1977; PhD, pharmacology, 1983; MD, 1984; all at Northwestern University

Training: Internship in medicine, 1984-85, anesthesiology residency and fellowship, 1985-1988, both at the University of Washington, Seattle

University positions: Vice chancellor for research, the Russell D. and Mary B. Shelden Professor of Anesthesiology, professor of biochemistry and molecular biophysics, Washington University School of Medicine

Family: Wife, Karen; sister, Lisa