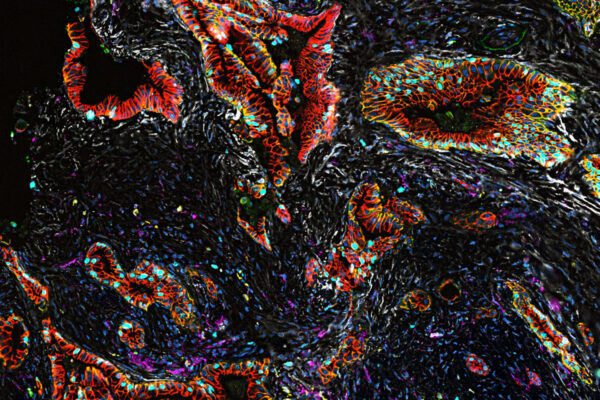

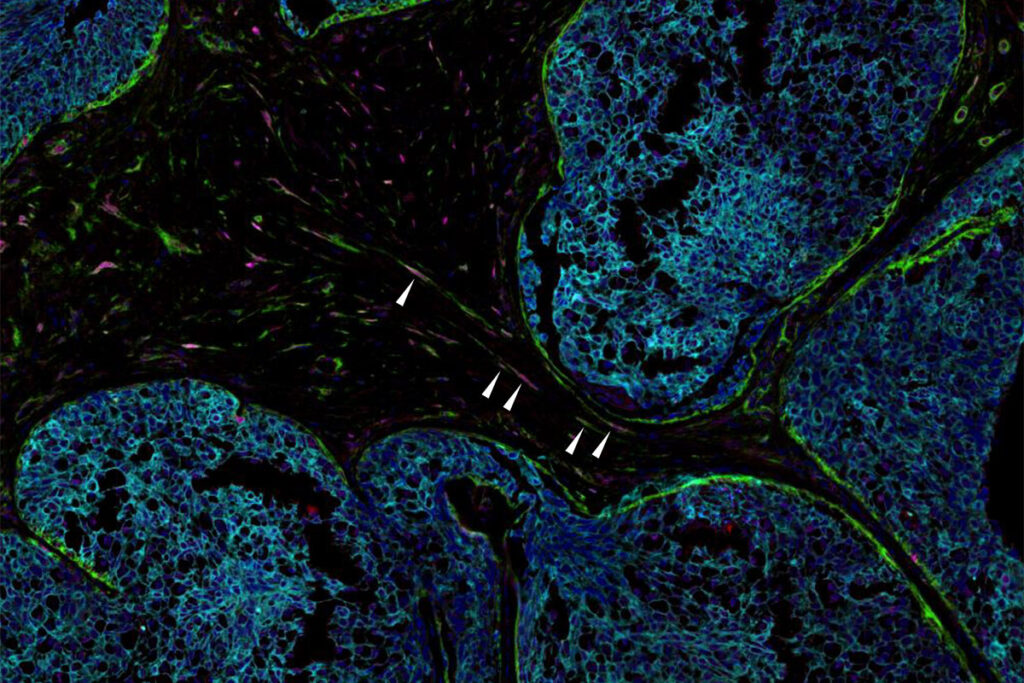

Two studies from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis focused on breast cancer and pancreatic cancer suggest that specific types of senescent cells — cells that have stopped dividing and drive inflammation — may play important roles in suppressing the immune system and allowing such tumors to grow unchecked. The research, led by Sheila A. Stewart, the Gerty Cori Professor of Cell Biology & Physiology, and David G. DeNardo, a professor of medicine, could lead to future breast and pancreatic cancer therapies that target senescent cells. Both studies are published in Cancer Discovery, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

In several types of breast cancer in mice, the researchers found that eliminating specific senescent cells in the tumor’s environment activated the immune system’s natural killer cells and other anti-tumor immune functions, suppressing tumor growth. In mice with pancreatic cancer, eliminating such senescent cells dialed up the immune system’s killer T cells and other anti-cancer immune functions, also restricting tumor growth. The research suggests that senolytic therapy, which targets senescent cells for elimination, could be added to breast and pancreatic cancer treatment regimens, helping to make immunotherapies and chemotherapies more effective. Some senolytic drugs are already Food and Drug Administration-approved to treat other cancers. Senescent cells modified immunity in different ways in breast and pancreatic cancer, which highlights the importance of research in disease-specific organs.