(Credit: Cheryl McDonald)

When Sarah Biffar was 20 weeks pregnant with identical twins, she found out during a routine ultrasound that her twins had a condition that caused blood to pass unequally between them. In twin-twin transfusion syndrome, the smaller twin pumps blood to the larger twin, causing the larger twin to receive too much blood and the smaller twin to receive too little.

Her physician, Anthony Odibo, MD, told Sarah and her husband, Alex, she needed to have emergency surgery. If she didn’t, there was a 90 percent chance her babies would die.

The next morning, Odibo made an incision the size of a pencil point to insert a small telescope into Biffar’s uterus. This tiny scope enabled Odibo to peer through the uterus into the placenta to identify which blood vessels in her twins to sever with a laser fiber.

The Biffars learned that the first 24-48 hours after the fetal surgery were critical. There was a chance both babies would die due to the stress of surgery.

The next morning, Odibo performed an ultrasound on Biffar and gave the reassuring words the Biffars were hoping to hear: “I see two heartbeats.”

Jade and Lily Biffar now are healthy 2-year-olds who love to sing and dance to their karaoke machine. They also know their ABCs and can count to 20.

“Dr. Odibo always made sure we understood what was going on,” Sarah Biffar said. “I felt like I was in the best hands. Dr. Odibo is a great doctor.”

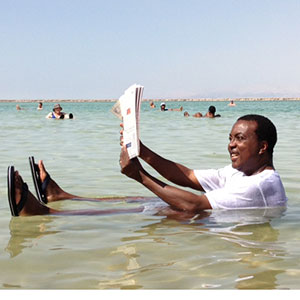

The amount of medical training Odibo received before learning the fetal surgery that saved Jade and Lily’s lives is dizzying. He earned a medical degree from the University of Benin in Nigeria, his home country; then completed a residency in obstetrics and gynecology and a research fellowship in maternal fetal medicine in the United Kingdom; a clinical fellowship in maternal fetal medicine, a residency in obstetrics and gynecology and a master’s degree in clinical epidemiology, all in the United States.

Once he discovered maternal-fetal medicine, a specialty that focuses on the care of the fetus and complicated, high-risk pregnancies, a combination of faith and perseverance guided him to continue his training to become more specialized and to enable him to practice in the United States.

Drive to excel

Today, Odibo is a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and one of the leaders of the Fetal Care Center, a joint effort of the School of Medicine and Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The Fetal Care Center is the only comprehensive facility in the Midwest that offers advanced fetal diagnostics, surgery before and after birth, and newborn medicine under one roof.

Odibo specializes in identifying and treating high-risk pregnancies, using ultrasound and genetic testing. In his research, he evaluates the effectiveness of fetal surgeries and diagnostic techniques before birth.

George Macones, MD, the Elaine and Mitchell Yanow Professor and head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, says Washington University is lucky to have Odibo. “Dr. Odibo is an internationally renowned expert with an incredible track record of research excellence,” he said. “In addition, he is a gifted clinician and an outstanding teacher, having mentored countless residents and fellows.”

Odibo attributes most of his drive and success to being one of 20 children. He is No. 9.

He grew up in a compound in Warri, a highly populated metropolitan area in an oil producing region of Nigeria. His father, a real estate businessman, was an African chief. This signified influence in the local community. His mother, educated in the West, taught home economics at a local university.

As in a lot of societies, Odibo said, if you were good in science or math, you were encouraged to become a physician. Odibo also realized early on that he wanted to be of service and help people.

Treating fetal problems

In his practice, Odibo sees anxious, distraught parents after an ultrasound has shown that their baby may not be developing normally. Odibo and his colleagues conduct further testing to determine if there is a problem. In the case of a fetal anomaly, Odibo and his colleagues must decide if minimally invasive fetal surgery could possibly correct the problem. They then communicate with the parents about potential treatment in addition to explaining the risks of fetal surgery. Minimally invasive fetal surgery can cause miscarriages, premature labor and infection.

“We have to be mindful of the stressful situations these parents find themselves in,” Odibo said. “We are able to correct the problem in 50 to 60 percent of cases. But even if there’s nothing that we can do, it’s rewarding to be able to help parents cope with the news they receive.”

In addition to treating fetuses with twin-twin transfusion syndrome, Odibo and his colleagues repair obstructed fetal bladders by inserting a tube into the unborn baby’s bladder to drain excess fluid. They also can treat amniotic band syndrome, which occurs when a strand of the amniotic sac membrane has wrapped itself around the baby. It can cause lost fingers and toes or prevent blood from the placenta reaching the baby if not treated.

Odibo and several of his colleagues have observed open fetal surgeries to prevent some complications in spina bifida and other neural tube defects. In these procedures, the surgeon removes the fetus at 22 to 26 weeks from the mother’s uterus, repairs the defect and returns the baby to the uterus. Odibo and his colleagues plan to one day offer these services here.

“This field is constantly evolving,” he said. “We need to continue to improve the equipment and develop better biomarkers to determine which fetuses will most benefit from surgery. But the potential is there to help families have healthy babies.”

A gracious seeker of knowledge

Winston Campbell, MD, professor and interim chairman of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine, served as Odibo’s clinical fellowship director in 1998. He said he feels like a parent basking in the success of one of his children in seeing how successful Odibo has been. “Anthony is a gracious seeker of knowledge, and he is very willing to share that knowledge with others,” Campell said. “And he is tireless in commitment to his clinical and research career.”

Odibo now is able to pass on his expertise and see the accomplishments of physicians he has trained. Katherine Goetzinger, MD, who trained under Odibo during her residency and fellowship and now as a junior faculty member, said she credits much of her success as a physician and as a scientist to his mentorship. “He is dedicated to his mentees with both his time and teaching skills,” said Goetzinger, assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology. “He always challenges me to continue to set high goals for myself while providing support and feedback along the way. I know I can come to him with any complicated research question or clinical dilemma, and he will be able to break it down and help me devise a manageable solution.”