With its saw-tooth façade and 9,000 square feet of windows, the $12 million UMSL at Grand Center building is at once dramatic and nimble — a light-filled and light-footed new home for St. Louis Public Radio, the award-winning NPR station.

It is also the first major built project for Axi:Ome LLC. Over the last decade, this small private firm has been featured in two monographs and won a handful of awards from the American Institute of Architects. Yet the bulk of its work remained conceptual and speculative — “paper architecture” in the lexicon of the field.

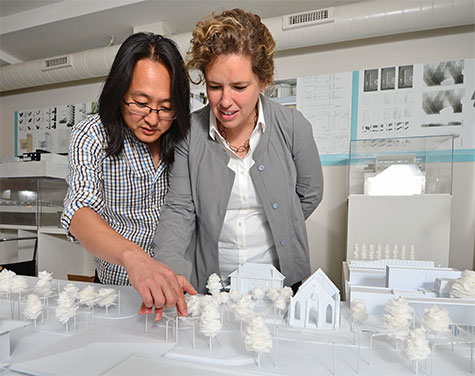

We sat down with founding partners Sung Ho Kim and Heather Woofter, both associate professors in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts, to discuss their practice, conceptual architecture and the path from paper to pavement.

Sung Ho, you grew up in New Jersey and Heather grew up in Maryland and Massachusetts. As transplants to St. Louis, what strikes you about the city? What are its defining characteristics, architecturally speaking?

Heather: St. Louis has incredible infrastructure. It used to be, what, the fourth-largest city in the U.S.? There are really beautiful old buildings, but also high-quality modernist structures from the 1950s and ’60s.

It also has incredible allegiance. I’ve never lived in a place where people care more about their city. They don’t want to become New York, they don’t want to become Los Angeles — they’re proud of St. Louis and they’re willing to invest in it.

Sung Ho: I remember the first time I saw the Gateway Arch, then walking around through all the different neighborhoods … . There is amazing opportunity here. St. Louis is like a sleeping giant. One day, it’s going to wake up.

You’ve both worked at larger firms but launched Axi:Ome in 2003. Talk a little about your approach.

Sung Ho: When we take on a project, it’s not just about budget and deadline. Our approach is to sort of turn things around and use the project as a way of asking more theoretical questions — about the building’s skin or form, about weight and lightness, about wind, temperature or the environment. For us, those are the questions that make a project interesting.

Heather: In a way, our academic positions give us a lot of freedom.

We’re able to make proposals — about particular buildings or entire districts — that aren’t simply client-driven. And then we find ways to make that work public and hopefully begin to generate interest and conversation.

What was the first official Axi:Ome project?

Sung Ho: Well, when we started, we did a lot of competitions and interiors projects, as well as pro bono work for non-profits … .

Heather: But the first was probably the Media Arcade. I had just arrived in St. Louis. Sung Ho was working with a developer who wanted to create an interactive media space on the site of an old gas station in Grand Center.

Even after it became clear the space wouldn’t be built, you continued working on the design. Why?

Sung Ho: That’s just the kind of people we are. [Laughs.] If we start something, we have to finish it.

Heather: In a way, that’s when the project really began for us. We took the basic premise and developed the idea of an arcade. The building skin became a series of media screens, constructed so that the image would “bend” from exterior to interior. The site was triangular, so we included three theater spaces, each looking to a different direction in the city.

Several design details — cantilevered upper floors, dark zinc exterior cladding, contrasting white window frames — seem like premonitions of UMSL at Grand Center. In retrospect, is it fair to say that the one influenced the other?

Heather: Well, working on the Media Arcade began a whole series of conversations with the leaders of Grand Center. A friend of ours, the architect and developer Aaron Novak, asked, “If you could do any project in the city, where would it be, and why?” We selected a parking lot on Olive, next to the Nine Networks building.

Which ultimately became the location for St. Louis Public Radio.

Sung Ho: Exactly. It’s an amazing site, surrounded by some pretty renowned buildings — The Pulitzer Foundation for the Arts, the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, the Sheldon Concert Hall. The challenge was to make a new building that could somehow incorporate and interact with the structures around it.

Heather: That’s the typical St. Louis condition. You have pockets of things that are just extraordinary, but how do you create connections between them?

Speaking of connections, tell us about Art Walk, your current Grand Center project.

Heather: Well, it encapsulates ideas we’ve been talking about for years. We were asked to do the conceptual design, as part of a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, but a lot of big logistical questions are still being worked out. Right now, it feels like the early stages of the UMSL building. You need something visionary to gather support and pull people together.

So what is the vision for Art Walk? What’s the problem it solves?

Sung Ho: Connectivity. Right now, it’s hard for pedestrians to move through the area — it has all these barriers. So, how do you cue people? How do you slow down traffic? It’s not just about putting up signs that say “arts district.” It’s about using light and sound and making beautiful things.

Heather: The path would start at Saint Louis University, cross Lindell Boulevard to the SLU Museum of Art, then come along the Scottish Rite Cathedral and into the media plaza between the UMSL and Channel Nine buildings. From there, it passes the Sheldon and takes a left turn down Washington Avenue to the Pulitzer, the Contemporary and the PXSTL site, and then along Spring to Enright.

Along the way, we’re proposing a series of interventions. Each would have a design distinction that would recognize the unique identity and perspective of each institution, but there’d also be some continuity between them.

You describe yourselves as the “in-between generation” — young enough to be comfortable in the digital environment, old enough to remember working by hand. Does technology change the way you design?

Sung Ho: No, not really — computers don’t alter the ways we perceive space or how we shape it. But they do give us the ability to test more situations.

Heather: Today, you can work with data that is more complex than an individual mind is capable of calculating. This allows you to get more complexity within the form. The computer generates the geometry, but the designer defines the premise and the problems you need to solve.

Sung Ho: Ten years ago, a small firm like us couldn’t have done something like Carbon Tower — basically, a tower without columns, in which a mylar “sail skin” helps to lift the building. The engineering software, to process wind patterns and other complex forces, would have been too expensive.

Heather: On the other hand, though we have all this technology, I think sometimes young designers can overlook fundamental properties of the environment. They don’t trust themselves to find the simple solution.

You met as graduate students — Sung Ho at MIT, Heather at Harvard’s GSD. As designers, what drew you together? What do you see as each other’s strengths?

Sung Ho: Heather’s strength is her understanding of human scale. What are occupants doing? How are they moving, what do they perceive? She’s able to look at a basic two-dimensional drawing and really understand the space, whereas I have to build a model. From the first conversation we had, I thought, ‘That’s the woman I want to work with,’ because she’s able to see things that I can’t.

Heather: Sung Ho has incredible formal ability. I don’t know anybody who is better sculpturally. He’s also very ambitious and has an incredible eye. He sends us right to the edge, in terms of form and the balance of numerous projects. I’m a little more realistic, a little more worried things will spiral out of control.

So we test each other. Between the two of us, it’s always a bit of a dance.