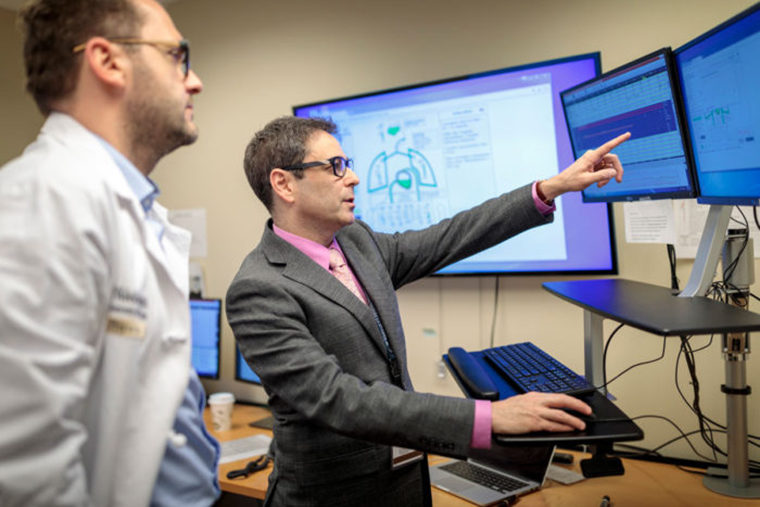

Michael Avidan and his colleagues sit in a windowless room in front of a panel of screens tapped into every operating room at Barnes-Jewish Hospital.

It’s conceptually similar to an air traffic control tower, except they aren’t tracking airplanes. Relying on customized software, the screens provide synthesized data about patients, keeping track of issues such as heart disease, diabetes and emphysema, as well as rapidly changing physiological measurements including blood pressure, heart rate, temperature, the brain’s electrical activity and other vital signs that anesthesiologists monitor during surgeries. Avidan and the others closely watch the data as part of a study examining whether such oversight can help provide better outcomes for patients.

Avidan, an anesthesiologist at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, zeroes in on one of the patients. “We can see where there potentially could be issues here,” said Avidan, MBBCh, the Dr. Seymour and Rose T. Brown Professor of Anesthesiology. “Based on everything we know about this patient, and concerning data that’s streaming live from the operating room, I worry about this patient’s risk for developing renal failure.”

Each day, a team of anesthesiologists, anesthesiology residents, and nurse and student-nurse anesthetists work together in the so-called Anesthesiology Control Tower to identify potential risks to patients and consider what measures might be taken to optimize those patients’ perioperative outcomes. As part of the study, they communicate with the clinicians in half of the operating rooms every day, making suggestions when deemed helpful.

For the other half of the operating rooms, control tower clinicians monitor what’s happening and note potential problems in a computer log. But they don’t intervene unless there is a threat to patient safety and well-being. The study, called ACTFAST, also includes other researchers from the Department of Anesthesiology and the Department of Surgery.

Read the full profile on the School of Medicine site.