Feeling a bit lethargic this week? It may have to do with the recent time change and a disruption to biological rhythms.

Erik Herzog, professor of biology in Arts & Sciences and a frequent voice of reason on this topic, said that sticking with standard time makes public health sense.

Time is what makes this scientist, well, tick. Herzog’s research is part of a growing body of work that shows the many ways in which circadian rhythms are central to human health and well-being.

He is also a gifted teacher and mentor. In honor of his work as principal investigator and director of the St. Louis Neuroscience Pipeline Program, and in recognition of more than 18 years of excellence in teaching at Washington University in St. Louis, Herzog recently received the Award for Education in Neuroscience by the Society for Neuroscience, the world’s largest organization of scientists and physicians focusing on the study of neuroscience.

A secret back door

For the past 18 years at Washington University, Herzog has shared his passion for neuroscience with students, developing a selective and popular undergraduate neuroscience track for upper-level undergraduates majoring in biology.

He has served as major adviser to more than 110 biology majors and mentored 52 undergraduates, seven graduate students and 11 postdoctoral fellows in their research efforts in his laboratory.

But he did not always want to teach neuroscience. As a child and through his undergraduate days at Duke University, Herzog wanted to be a marine biologist.

“I had read every book and watched every TV show with Jacques Cousteau,” Herzog said (his personal favorite was “The Living Sea”). He trained as a scientific diver, and even talked his way onto a marine research expedition in Antarctica.

“When I went to Syracuse to get my PhD, it was in neuroscience — but I was working on a marine organism,” he said. “I was convinced that this was my secret back door into being a marine biologist. Everyone told me that it’s really hard to be a marine biologist; you need to do something special.”

Herzog worked with horseshoe crabs — homely sea creatures with remarkable eyes that allow them to see equally well in light and in darkness.

“I spent most of my thesis (days) putting a camera on top of a horseshoe crab and filming the world as the horseshoe crab swam around, and then simultaneously recording the optic nerve activity from individual optic nerve fibers,” Herzog said.

“We could take a video of what the horseshoe crab had seen in the real world and play it to a computer model — and actually generate computer responses that looked like the optic nerve responses that we had recorded.”

“It got me excited about trying to learn how this eye works day and night,” he said.

Timing is everything

Herzog completed his PhD at Syracuse University under the direction of Robert Barlow Jr., a vision scientist. Herzog credits Barlow for helping him to think about computational modeling in his own research, instilling in him the importance of a quantitative approach.

But it was his postdoctoral adviser, Gene Block, then at the University of Virginia’s National Science Foundation Center for Biological Timing, who taught him how to critically evaluate a scientific question. Block is now chancellor of the University of California, Los Angeles.

“Gene is a person who listens to other people’s ideas,” Herzog said. “He really taught me how to listen, how to recognize the exciting questions and how to begin to answer those questions.”

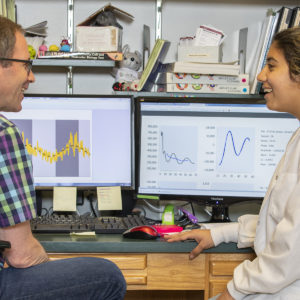

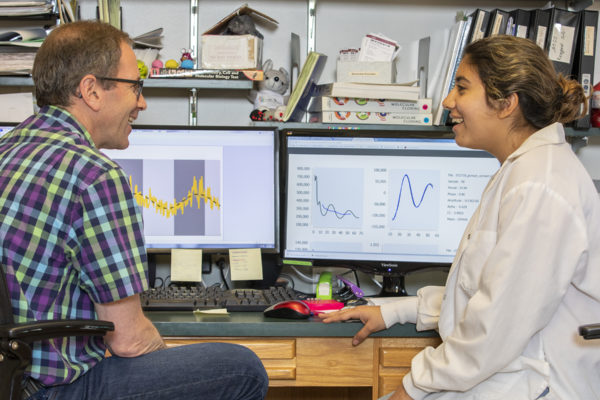

These days, Herzog and the researchers in his lab study the cellular and molecular basis of circadian rhythms in mammals using techniques that include planar electrode arrays, cellular imaging and genetic manipulations.

His research group recently published a study on how light resets the circadian clock in mammals. They also discovered that by activating a small subset of the neurons involved in setting daily rhythms, they can unlock a cure for jet lag in mice, a finding they reported in the journal Neuron.

The banner at the top of the Herzog lab webpage sums it up: “Timing is everything.”

But even if timing is everything, opportunity plays a role. It’s a mantra that rings true for Herzog, who has made much of his own opportunities and now is focused on making space for others to succeed in neuroscience careers.

For Herzog, this means welcoming and encouraging young people from diverse backgrounds to consider a life in science.

Neuroscience in our own backyard

Herzog holds or has held leadership positions with several organizations, including as president of the St. Louis Society for Neuroscience Chapter, chair of Neuroscience Outreach at Washington University, co-director of the university’s neuroscience PhD program and president of the Society for Research on Biological Rhythms.

In these positions, Herzog has worked to increase the numbers of women and people of color in the neuroscience workforce.

He gives additional time to mentor, recruit and teach high school students through outreach efforts such as NeuroDay and the Young Scientist Program at Washington University. He is a faculty fellow for the university’s Institute for School Partnership, which aims to boost STEM education in local K-12 schools.

“We have an opportunity in St. Louis to bring in new kinds of researchers to the field,” Herzog said. “St. Louis is a vibrant, diverse city, and many of the people who traditionally would not go into the neurosciences might be right here in St. Louis.”

“If we could encourage them to think about neuroscience research as a possible career choice, it could really improve the field of neuroscience,” he said. “We work on very diverse issues, ranging from stroke — which disproportionately affects African-Americans — to other topics that might be of great interest to young scientists, things like bipolar disorder, which tends to have onsets in the teen years.”

One of the programs that Herzog has helped create to bring neuroscience to more local kids is the popular St. Louis Area Brain Bee.

This year’s neuroscience competition consisted of 58 students — the largest turnout ever. Twenty-nine high schools were represented in the 2019 competition.

“Some students have done this for the past couple of years and they’re here again,” Herzog said. “That’s really encouraging for the future of neuroscience! The high level of intelligence, energy and enthusiasm of students at such a young age is inspiring.”

People are a key to success

Herzog loves his work and especially the opportunity to interact with students, other researchers and members of the public who have an interest in the brain and biological rhythms.

“For me, the best thing about my job is the people that I work with,” he said.

His advice to aspiring researchers: Always have both a solid project and a high-risk project on deck.

“If you’re having a good time in the lab, if you’re making the right choices about your projects, your mentors, your friends, your colleagues — then it’s a great job,” Herzog said. “That’s a theme here. You have to take control of who you surround yourself with and what you are doing. Because this is a job with complete freedom.”

He is also happy to share a trick that might help any person break out of a daylight saving time funk.

“I bike to work every day,” he said. “It gives me a little bit of exercise. It gives me a little bit of time to myself to think. When I arrive at work, I’m ready to roll. And then when I get home, I’m ready to sleep.”