In 2014, the Washington University Prison Education Project launched its first two classes at the Missouri Eastern Correctional Center in Pacific, Mo.

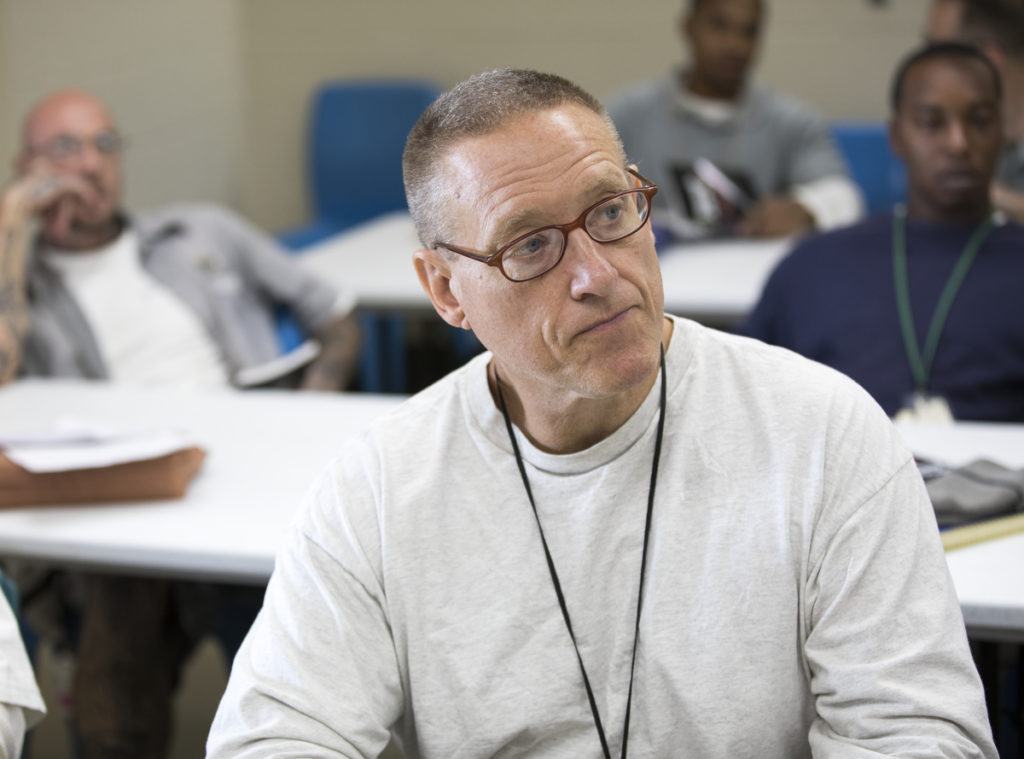

In the years since, more than 20 faculty from across Arts & Sciences have taught archeology, drama, history, literature, math, philosophy, physics, psychology, writing and other topics to more than 40 participating students.

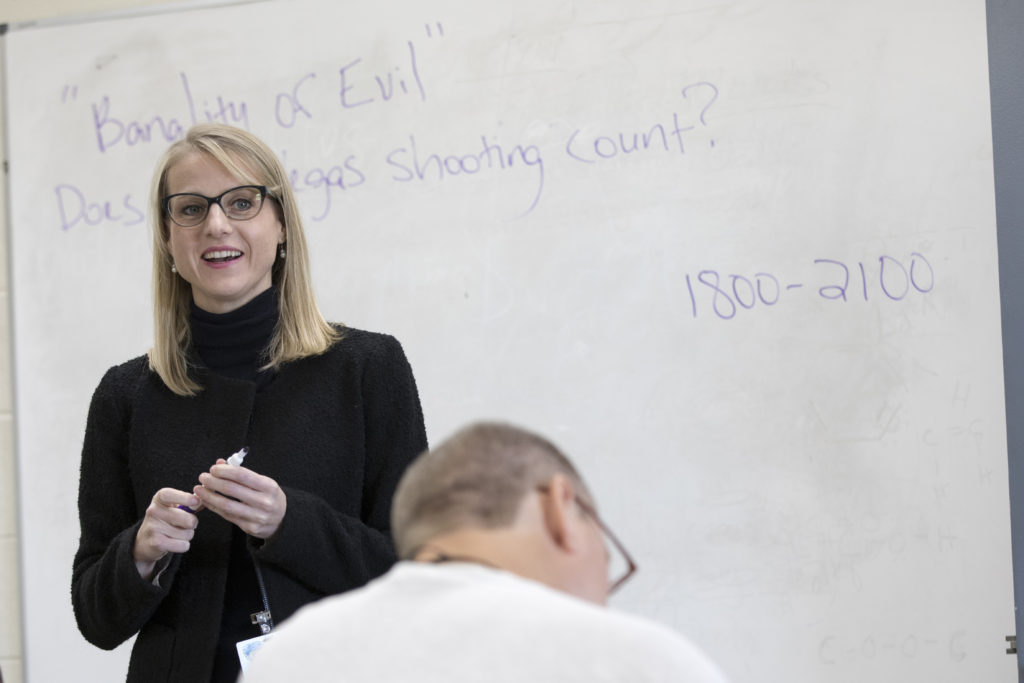

In this Q&A, program manager Jennifer M. Hudson, lecturer in political science, discusses the Prison Education Project, its animating philosophy and the importance of the liberal arts.

Your background is political theory. Tell us about your work.

I study the concept of bureaucracy and its relationship to democracy. How do bureaucracies shape politics and our lives? We’ve been trained to think about it in a certain way, which doesn’t necessarily match what we see today, in both public and private sectors.

Today, certain jobs are organized in ways that suggest freedom. You’re your own boss if you drive for Uber. But the structure is profitable because the organization is able to monitor everything you do and to incentivize certain behaviors.

That’s bureaucratic management, shaped by a bureaucratic mentality, even if we don’t always recognize it as such.

So bureaucratic control still exists, even if the mechanisms are subtler.

Yes, exactly. Your boss may not be watching your desk, but everything is managed and measured. The bureaucracy is more diffuse, but the mentality is still there.

You previously taught for the Bard Prison Initiative and joined the Washington University Prison Education Project last fall. How would you characterize the program’s philosophy?

This is college that happens to take place in prison. That’s the heart of it.

It’s also about demonstrating the relevance of the liberal arts more broadly. We can all agree on the importance of STEM fields, and the need for practical skills. But the humanities help you see the world in a different way. Raw data doesn’t speak for itself. Human beings have to gather it and interpret it, and the humanities help you to do that, in any arena. They also give you a sense of ownership, in your own life and in the larger community of ideas.

Taken literally, “liberal arts” means the art of being free. That’s what our project is.

What’s the most common misperception about teaching in prison?

I had an interesting conversation with a student a while back. Someone had asked him if he was basically “one of the good guys” who had just taken a wrong turn somewhere and got caught up in the system. And he found that idea insulting because it denied his agency and recast him entirely as a victim. In fact, he takes full responsibility for the choices that landed him in prison.

I’ve also had students question the dividing line between nonviolent and violent offenses. Even if you’re “only” selling drugs, you can still be part of a social structure in which violent things take place.

Some people assume all of our students are nonviolent offenders brought up on drug charges. We don’t look into backgrounds — so I really don’t know what their charges are — but being in a medium-security facility only means you’re close to being released. And the charges turn out to be irrelevant when it comes to the question of whether a person can thrive academically.

It sounds like participants truly grapple with the idea of rehabilitation.

They have to. And I think we have to, as a country. We put so many people in jail that we need to find ways of living together again in society.

The Prison Education Project was launched with a grant from the Consortium for the Liberal Arts in Prison but is now fully funded by the Office of the Provost — the only program of its kind entirely supported by a single university. How does that shape your work?

Many college-in-prison programs rely on a volunteer work force. That can be problematic because it means they mostly recruit a certain type of person, which further separates what’s happening in those classes from what’s happening on the rest of campus.

As much as possible, we want the Prison Education Project to replicate the kind of rigorous, high-quality education available to all Washington University students — and that begins with faculty recruitment. This is not a remedial program or a community service or campus activism program. It’s about serious academics.

In its first year, the project offered five courses. Last year, you had 13, including two for prison staff, as well as two noncredit workshops. How else would you like to grow?

Well, we’d like to offer more classes, particularly in math and the sciences. Next year, we’ll have our first graduation ceremony, for people earning associate’s degrees. We’re also beginning to present speakers, symposia and other events, both on campus and in the prison. The ambition is to establish the Prison Education Project as a broader intellectual center for thinking about the role of higher education in democratic society.

Participating faculty are encouraged to use the same curricula they use for campus classes. But is there anything you have to approach differently, pedagogically speaking?

The biggest difference is just that students are older. As an adult, you have a lot more experience trying to manage your life, which often involves navigating bureaucratic structures and dealing with pressures that college students may not have encountered. But otherwise, it’s more similar than you might think.

Sometimes, during class, it’s easy to forget where you are. I remember one student mentioning, just as an aside, that he “couldn’t wait to get out of here.” And I asked, “Why? Am I boring you?”

But, of course, he didn’t mean the classroom.

At 4 p.m. Wednesday, Nov. 15, Hudson will host a book discussion with Daniel Karpowitz, director of policy and academics for the Bard Prison Initiative and author of “College in Prison: Reading in an Age of Mass Incarceration.” The event is co-sponsored by the School of Law’s Public Interest Law & Policy Speakers Series. For more information, visit prisonedproject.wustl.edu.