A fascination with science always has been evident and plentiful in Tamara Hershey’s childhood home — from a homemade telescope to sunspot charts to rainfall measurement graphs. As a young girl, Hershey wasn’t sure what area would suit her best, but she always knew she wanted to be a scientist.

Some 25 years after college, Hershey, PhD, still doesn’t exactly fit into a traditional job in science.

“I’ve never pigeonholed myself,” she explained. “And I have been extremely fortunate to ‘grow up’ as a scientist in a place like the Neuroimaging Labs and the psychiatry department at Washington University, where nobody told me I needed to focus on a specific disease or problem.”

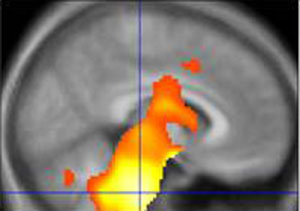

A professor of psychiatry at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, she has spent her career using brain-imaging tools to conduct research on diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, obesity, Tourette syndrome and Wolfram syndrome. She has looked at the brain with positron emission tomography (PET), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), paying particular attention to how the brain is affected by diabetes.

“I definitely took an unusual path, and along the way, a lot of endocrinologists wondered why I was studying the brain if I was interested in diabetes,” said Hershey, who also is a professor of neurology and of radiology. “But the brain uses more glucose per pound than just about any other organ in the body, so it’s an extremely needy and greedy organ, and fluctuations in the glucose supply can have a major impact on brain function acutely and long-term.”

Her interest in the brain and behavior also helps to explain how a diabetes researcher ended up working in a psychiatry department.

“Tammy is an outstanding neuroscientist,” explained Charles F. Zorumski, MD, the Samuel B. Guze Professor and head of the Department of Psychiatry. “Her dual background in cognitive science and neuroimaging positions her uniquely to study how disorders from diabetes and Parkinson’s disease to psychiatric illnesses can alter brain function. And her studies in obesity and brain glucose utilization position her to make contributions that will have a major impact on public health problems.”

A look at brain function

Hershey began her science career when MRI and fMRI were emerging as tools that researchers could use to observe brain structure and function. After completing her doctorate in psychology at WUSTL, she did an internship in New York and then returned to the School of Medicine for a postdoctoral fellowship with Joel S. Perlmutter, MD, professor of neurology, of radiology, of neurobiology, of occupational therapy and of physical therapy.

Perlmutter studied neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, but Hershey also had an interest in diabetes. During her fellowship, she worked in both areas.

“Here we have Joel Perlmutter taking me on as a postdoc,” she said. “He’s researching Parkinson’s disease and movement disorders, and I came in and said, ‘I want to learn with you, but I’d also like to do some diabetes research, OK?’ And he had no problem with that. Later, Chuck Zorumski took me on in psychiatry, and I said, ‘Here’s my portfolio: Parkinson’s disease and diabetes.’ And he said, ‘That sounds great. Go for it.’”

She credits that freedom to pursue diverse research interests with advancing her career — and advancing the understanding of the intersection between diabetes and neurodegeneration.

“It was gratifying at this year’s meeting of the American Diabetes Association because they put out a book called Diabetes and the Brain, which was a collection of papers published in ADA journals,” she said. “Ours was one of the most frequently cited labs in the publication.”

A brain perspective

Recently, Hershey and a team of leading neuroscientists and endocrinologists received a program project grant looking at potential connections between disorders such as diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. Her part of the grant involves studying how glucose metabolism in certain brain regions is affected by high levels of glucose and insulin.

“My involvement with this team started when Marc Raichle (MD, professor of radiology, of psychology, of biomedical engineering, of neurobiology and of neurology) was giving talks on how the brain metabolizes glucose within a certain brain network, and my colleague Ana Maria Arbeláez (assistant professor of pediatrics) and I wondered what happens to this network when you have too much glucose in your system,” she said. “That led to several discussions with Marc and, eventually, this program project emerged.”

A similar series of discussions got Hershey involved in studying a severe form of diabetes called Wolfram syndrome. Several years ago, Alan Permutt, MD, former professor of medicine and of cell biology and physiology, discovered the Wolfram gene. He was organizing a registry of patients, and because Hershey studied the effects of diabetes on brain structure and function in children, Permutt, now deceased, asked whether she’d like to be involved in the Wolfram clinic.

“Endocrinologists usually are interested in Wolfram syndrome because it’s a genetic form of diabetes,” she said. “But the diabetes aspect of the disorder isn’t what limits the lifespan of a patient. It’s the features outside of diabetes that are so devastating: optic nerve atrophy and neurodegeneration in the brain stem. Before we began our studies, Wolfram syndrome had not been examined extensively from a brain perspective.”

Family time

Hershey wasn’t the first scientist in her family. Her father, John Hershey, earned a PhD in astronomy. She recalls growing up with a scientist in the house as a challenge. Family arguments and discussions were common at the dinner table with Tammy, her older sister, Virginia, and her younger brother, John, also a scientist.

“You didn’t get to do things unless you could lay out an air-tight argument,” she said. “There was not a lot of tolerance for off-hand impressions or poorly formed opinions. You’d better have some data.”

These days, Hershey admitted, her own children may face even greater challenges. Hershey’s husband, Steven Mennerick, PhD, is also a professor in the Department of Psychiatry and a neuroscientist, and they tend to demand data from their 14-year-old son, Eli, and 12-year-old daughter, Grace.

“We have them lay out arguments for us, logical arguments,” she said. “We want to hear reasons why something is a good idea. You know, if you want a new electronic device, show us the cost-benefit analysis, the rationale and the payment plan.”

Hershey said she and Mennerick have been fortunate. Rarely have they faced grant deadlines in the same cycle or served on study sections at the same time. They schedule weekdays so that one of them goes to work early while the other takes the kids to school. Then the one who went to work early gets the kids to soccer practice or music lessons, while the other stays in the lab to work later.

Outside of the lab, Hershey has spent considerable time and effort with the Academic Women’s Network (AWN), working to make careers in science more feasible for women at the School of Medicine.

“We have helped improve and expand child-care and maternity-leave options,” she said. “We also now have a stop-the-clock option for tenure-track faculty when you have a major life event, like a new baby at home. I think the AWN and the gender-equity committee have accomplished a great deal.”

When her own children were born, Hershey had to find other ways to make things work. But she believes that, in retrospect, everything worked out fine.

“I decided early on that there were certain things I wanted to do for my kids, and if that meant my career was affected in a negative way, then that was OK,” she explained. “I was willing to take that hit. But in the end, I can’t imagine how it could have worked out any better.”