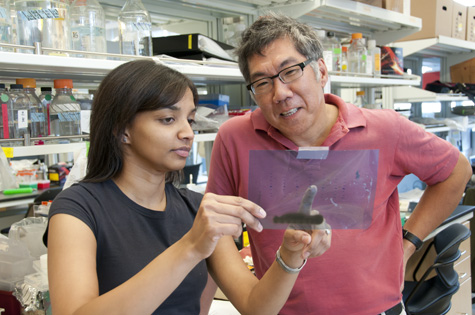

Robert Boston

Shuba Srivatsan (left), a graduate student, and Andrey Shaw, MD, look at some recent protein expression data that Srivatsan generated in the lab. “Andrey is not only an exceptional and visionary scientist but also a true humanist, interested in everything and everyone,” says Herbert W. Virgin IV, Edward Mallinckrodt Professor and head of Pathology and Immunology. “He’s kind and thoughtful while at the same time being perceptive and incisive.”

Andrey Shaw, MD, faced a tough decision after he earned his undergraduate degree.

Shaw, the Emil R. Unanue Professor of Immunobiology in Pathology and Immunology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, had a bachelor’s degree in music from Columbia University. He had also developed his piano performance skills across the street at the Manhattan School of Music. His brother and roommate, Rob, also was studying music.

But Shaw was increasingly worried that getting up in front of crowds to perform music was too stressful. He had started to think about following his father’s career path and becoming a physician.

“I had taken minimal math and science classes as an undergraduate and decided to apply to medical school,” he says.

After he was accepted at Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons, Shaw struggled a bit with the transition from studying music to studying medicine.

“I was spending most of my days practicing piano, and I flunked my anatomy final,” Shaw says. “That was kind of a wake-up call, so I stopped playing the piano and started to focus on medical school.”

Shaw’s just a little wistful for the path not taken and occasionally wishes he could sit down at the piano and take the time to learn a composition by Maurice Ravel or to play a piece by Frederic Chopin or Franz Liszt.

But one of the biggest reasons Shaw can’t get that time is because he’s having so much fun doing research.

“I’ve been lucky enough to practice a kind of science where I can follow any question that looks interesting to me,” says Shaw, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator. “It’s been incredible.”

A home in the sciences

Shaw was born in Texas, but his family moved to Seattle two years later. He had three siblings: older sister Wen, younger sister Kathy, and younger brother, Rob. Wen died two years ago. Rob is now a freelance violinist in New York City; Kathy is a chef in Ottawa for Le Cordon Bleu.

Unsure of what he wanted to do after medical school, Shaw decided to specialize in pathology at Yale, a choice that he admits is unusual for someone who gets seasick looking into the microscope and is colorblind. Struggling as a pathologist, he looked forward to his research rotations. He remembers arriving in the lab of his mentor, Jack Rose, PhD, as a high point.

“I was 30 years old, my wife, Cynthia Florin, had just given birth to our first child, our daughter Emily, and I looked around the lab and knew I’d finally found what I wanted to do,” Shaw says.

He notes that there are actually quite a few similarities between science and music.

“They both are crafts that require dedication to repetitious exercises — rehearsal and bench research — that are boring but also are a means to very joyful ends — performance and discovery,” he says.

Shaw didn’t realize that there’s an additional similarity between music and science until after he had completed his research training: Scientists also have to get on stage and “perform” when they give presentations on their work to other scientists.

At that time, Rose studied how viral proteins move around host cells and across cell membranes, a group of processes called trafficking. Shaw decided to investigate the trafficking of the CD4 receptor protein, which other scientists had recently identified as the receptor that HIV binds to at the start of infections.

When Shaw found that CD4 was linked to an important class of signaling proteins known as tyrosine kinases, Rose put him in touch with a colleague who knew more about those proteins so he could continue the studies. His work on the topic eventually led to a presentation at a scientific meeting, where he met Matt Thomas, PhD, then a member of the pathology and immunology faculty at WUSTL. Thomas asked him to come visit the campus.

“I knew Washington University in St. Louis did outstanding research,” Shaw says. “But what I didn’t know or expect was that there were grass and trees in St. Louis and how clean everything is.”

A ‘fascinating persona’

Emil Unanue, MD, then the head of the Department of Pathology and Immunology at Washington University, hired Shaw in 1991. Unanue, now the Paul and Ellen Lacy Professor of Pathology and Immunology, quickly put Shaw to work co-teaching the immunology class with him.

“I wasn’t an immunologist when I came here, but Emil encouraged me to become one,” Shaw remembers with a smile. “He helped me focus on some of the important immunological questions of the day.”

Unanue calls Shaw a polymath, a term for a person with extensive knowledge and interests in a broad range of fields.

“His scientific curiosity has led to important contributions not just in immunobiology, the division in our department that he directs, but also in kidney physiology and pathology,” Unanue says. “He’s also seriously interested in classical music, literature, politics and human behavior. He is a truly fascinating persona.”

“Andrey is not only an exceptional and visionary scientist but also a true humanist, interested in everything and everyone,” says Herbert W. Virgin IV, Edward Mallinckrodt Professor and head of Pathology and Immunology. “He’s kind and thoughtful while at the same time being perceptive and incisive.”

While describing his research, Shaw says he tries to help students follow their own scientific interests. His policy, “to meet them halfway,” is reminiscent of the support he received from his mentor at Yale.

Shaw and two colleagues, Paul Allen, PhD, the Robert L. Kroc Professor of Pathology and Immunology, and Michael Dustin, PhD, of New York University, created the immune synapse hypothesis, an influential explanation for how key immune cells become activated to fight invaders. According to the theory, the immune synapse is a specialized arrangement of receptors created by a T cell binding to its target that then triggers activation of the body’s defenses.

While investigating a protein important to this synapse, Shaw discovered that knocking the protein out in mice led to fatal kidney failure. With colleague Jeff Miner, PhD, Professor of Medicine and Cell Biology and Physiology, he showed that the protein, CD2AP, is vital for podocytes, an important cell type involved in the kidney’s work of filtering wastes from the blood.

In more recent studies, Shaw’s work in this area led him to become involved in efforts to identify genes linked to focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, the second most common cause of kidney failure after diabetes. His lab has identified two of the eight genes so far known to contribute to the disorder.

“I’m still active in a lot of basic research in immunology, but as I’ve grown older, I find myself thinking more and more about research problems with greater potential for immediate clinical relevance,” he says.

Fast Facts about Andrey Shaw

Lives in: University City, Mo.

Wife: Cynthia Florin, MD, a psychiatrist in private practice

Children: Emily, 24, a graduate of Haverford College; Alex, 22, a graduate of Columbia University

Music: Lets the iPod “run on shuffle”

Sports: golf every Sunday; tennis a few times a week

Favorite restaurants include: Royal Chinese Barbecue in University City, Niche in Benton Park, Pomme in Clayton

Arts: The Saint Louis Symphony, Opera Theatre of St. Louis

Active supporter of: Upstream Theater, Discovering Options, Sherwood Forest Camp