Robert Boston

Ken Yamaguchi, MD (right), and orthopedic surgery fellow Nady Hamid, MD, discuss an image of a patient’s injured shoulder. “Ken constantly challenges himself,” says Richard Gelberman, MD, the Fred C. Reynolds Professor and head of Orthpaedic Surgery. “As a department head, you wish everyone were like Ken Yamaguchi.”

Some in medicine decide on their career path while still in grade school. Ken Yamaguchi was not one of them.

“I decided on medical school at the end of my senior year of college,” he says. “I was a predental student because I thought physicians had to work too hard.”

A self-described “average” student, his grades improved significantly once he decided on medicine.

“It was like a light bulb turned on,” he says. “I did very well toward the end of college and in medical school, I think, because I was so excited. I felt like I found what I was born to do.”

Yamaguchi, MD, now the Sam and Marilyn Fox Distinguished Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery at Washington University School of Medicine, earned a bachelor’s degree in biology and a master’s degree in microbiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, before relocating to George Washington University School of Medicine in Washington, D.C.

It was there that he decided on orthopedics as a specialty, but to be fair, he long had been an admirer of a particular orthopedic surgeon.

“I grew up as a Dodgers fan,” he says. “I guess I was a typical kid in Los Angeles who fell asleep listening to the Dodgers on the radio with Vin Scully, and because I followed the Dodgers closely, I knew about Frank Jobe, and I idolized him.”

In 1974, Jobe, MD, the Dodgers’ team physician, performed ligament transplant surgery on Tommy John’s pitching elbow, allowing John eventually to pitch again. So-called “Tommy John” surgery is now the standard of care when pitchers tear the ulnar collateral ligament in their pitching elbow.

Preparing for a post-residency fellowship, Yamaguchi faced a decision. He was attracted to shoulder surgery, but there were only three shoulder training programs in the country. Rather than trying his luck with only those programs, he also applied for sports medicine fellowships, including one at the Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic in Los Angeles — Jobe’s clinic.

“They accepted me, which was a dream come true,” he says. “I told my chairman I was going to go, but I still had an interview at Columbia University for a shoulder fellowship, and I decided not to cancel it.”

That was a good decision because he also loved Columbia. When they offered him a spot, he decided to make shoulders his specialty. But it still worked out because he later became friends with Jobe and even did surgery with Jobe before Jobe retired.

Rotator cuffs

During his residency at George Washington University, Yamaguchi not only learned orthopedic surgery, he also met Dan Riew, MD, now the Mildred Simon Distinguished Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery at Washington University in St. Louis.

“You really get to know someone’s true nature when you go through the trials and tribulations of residency together,” Riew says of Yamaguchi. “And right from the start, it’s been clear that he’s just an outstanding leader who puts the interests of others ahead of his own. And I think most people ‘in the know’ recognize that he is simply the best shoulder surgeon in the world.”

He’s one of a few shoulder surgeons around with a clinical RO1 grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). That grant, which just was renewed, involves the study of rotator cuff tears. Although NIH supports orthopedic research, the vast majority of funded investigators are basic and translational scientists rather than clinical surgeons like Yamaguchi.

“When I first came here, I met Dr. Bill Middleton on the elevator,” he says. “He and his partner, Dr. Sharlene Teefey, were true pioneers in the use of ultrasound in the shoulder, and soon I was referring patients to them. It turns out they routinely did ultrasound exams on both shoulders to compare the injured side to the normal side. That gave us a unique and exciting research opportunity.”

With rotator cuffs, Yamaguchi had learned that tears often occur in pairs. So he asked the radiologists if they were seeing many patients with tears in both shoulders. Sure enough, they had noticed that in many patients, even in those who didn’t have pain.

“They had inadvertently discovered a whole population of people with rotator cuff tears but no pain!” Yamaguchi says. “That was the start of our research. We’ve been able to watch a whole population with tears with no pain and observe as some of them develop pain to find out what might cause them to go from ‘pain-free’ to ‘pain-ful.’ ”

Yamaguchi says age is the most important factor. Genetics plays a role, too. Although many think of rotator cuff tears affecting athletes, most people with tears are sedentary. In fact, almost 50 percent of people over age 70 have rotator cuff tears, either with or without pain.

Rotator cuff surgery once was one of the most painful operations around, but over the years, Yamaguchi has developed less-invasive techniques that make the post-operative period easier and help people return to normal activities sooner.

Shoulder and elbow replacement

But in the worst cases, a bigger operation still is required, and that may mean a total shoulder replacement. Yamaguchi helped design the prosthesis he uses, and he is enthusiastic about the results.

“When I know there’s a patient in the clinic who is back for a follow-up, I like to get to that exam room quickly because I know I’ll see a happy face,” he says. “It really is a wonderful operation for the people who need it.”

He also does elbow replacement, using a different device he helped design.

“That’s also a remarkable procedure,” he says. “When it comes to making a difference and improving people’s quality of life, it doesn’t get much better than those two operations.”

Yamaguchi didn’t add the elbow to his repertoire until after he came to Washington University. His fellowship training had involved only the shoulder.

“But when I came here, I asked Dr. Richard Gelberman to send me to the Mayo Clinic for training in elbow surgery,” he says. “So I started my practice here and then left for the Mayo Clinic to get supplemental training. I went back several more times over the ensuing months and learned about nearly every type of elbow operation in their book.”

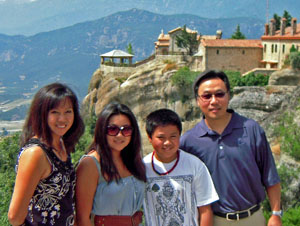

Courtesy photo

The Yamaguchi family in Greece last Christmas: (from left) wife, Kathy; daughter, Kelli; son, Kyle; Ken Yamaguchi.

He used that expertise to create a fellowship program at WUSTL that combined the shoulder and the elbow. He directed that program from 1999-2004.

“Ken constantly challenges himself,” says Gelberman, MD, the Fred C. Reynolds Professor and head of Orthpaedic Surgery. “He’s a remarkable investigator and a world-class surgeon. There’s no one better. He’s been the teacher of the year. And as a department head, you wish everyone were like Ken Yamaguchi.”

When he’s not at the hospital, Yamaguchi likes to play tennis weekly. He also loves golf, frequently partnering with his chairman on weekends when both are in town — “He’s getting better,” Gelberman deadpans — and he coaches his son’s baseball team during the summer.

“We keep the kids on a strict pitch count,” he says. “They are teenagers now, so I have actually started teaching them to throw a curve ball this year, but I work hard to teach them proper throwing mechanics.”

The last thing he needs is a teenaged Tommy John.

Fast facts about Ken Yamaguchi

Family: Wife, Kathy Taeko Yamaguchi; daughter, Kelli Emiko, 18; son, Kyle Kiyoshi, 13

Hobbies: Golf, tennis, baseball and snowboarding

Extra education: Enrolled in the Executive MBA program at the Olin School of Business