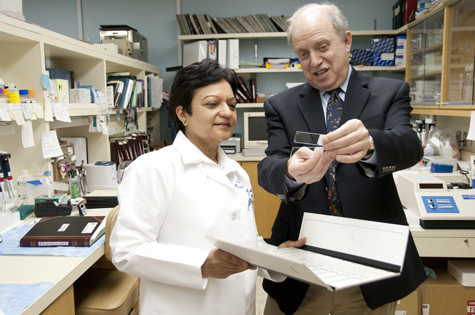

Robert Boston

Alan Pestronk, MD (right), in his lab withi Rati Choksi, senior research technician. “Alan is one of the premier academic clinical neurologists in the area of neuromuscular disease in the world,” says David Holtzman, MD, the Andrew B. and Gretchen P. Jones Professor and head of Neurology. “He has developed numerous different novel blood tests that are useful in the diagnosis of a variety of disorders, and his website is one of the most utilized neurology websites worldwide.”

Alan Pestronk, MD, is a fan of detail who remembers key moments in his life with remarkable clarity.

He can recall, for example, how his interest shifted from mathematics to medicine at the afternoon tea-and-cookie socials in the mathematics department at Princeton University.

“At those gatherings, I decided that I wanted a career that was more involved with people,” says Pestronk, director of the Neuromuscular Division in the Department of Neurology and professor of neurology and of pathology and immunology.

Pestronk remembers when he decided to become a neurologist as well. Six weeks into medical school at Johns Hopkins University, he began reading a series of articles about the wiring of the brain in the journal Experimental Brain Research. They were written by Sir John Eccles, DPhil, a Nobel laureate, and detailed the circuitry of nerve cells in the cerebellum. Pestronk, who had specialized in network theory as a math student, found the articles addictively fascinating.

“I became so interested in it that I would go to the library on the day the journal was due to come out and look for its arrival,” he says. “That’s when I knew I was going to become a neurologist.”

Pestronk also remembers what it felt like years later to diagnose his first wife with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a relatively rare and relentlessly fatal neuromuscular disorder that he treats in his Neuromuscular Disease Clinic.

“It was terrifying and comforting at the same time,” he says. “I knew exactly what was going to happen, so the good part about it was that we could deal with everything realistically and not be diverted by false hopes or false fears.”

Finding a cause

Pestronk credits the experience with teaching him a great deal about how to be a better doctor. He says it helped him understand the terrible toll that diagnosis with an untreatable disease takes on patients and their families.

“I’m much more attuned not only to the patient but also to the person who is sitting in the room with them,” he says. “I know what those caregivers go through, because I went through it.”

Ilene Edison died approximately a year after her diagnosis. But before she did, she extracted a guarantee from her husband.

“She made me promise that I would use this experience in a positive way,” he says. “So I channeled my grief into creating our neuromuscular website, which fit well into my interests in detail and in giving back to the world.”

The resulting site (neuromuscular.wustl.edu), now in its 16th year, is so authoritative, extensive and well-used that it typically is the first site listed in Google search results for the term “neuromuscular.” More than 3,000 unique visitors access the site on most days; about 50 percent are physicians. It typically is accessed by people in 100 countries and all 50 states on a daily basis.

Diagnosis usually is one of the toughest parts of treating neuromuscular disease, and the website includes detailed descriptions of the symptoms and pathology of thousands of different neuromuscular disorders.

“There are so many genes involved in the development, maintenance and repair of the neurological and muscular systems, and mutations in many of them can lead to disorders,” Pestronk says. “Those genes can also be targets for immune disorders. And problems caused by toxins and nutritional deficiencies just add to the diagnostic challenges.”

According to Pestronk, the Neuromuscular Disease Clinic, one of the biggest and busiest of its kind in the country, confronts these challenges with a unique array of expertise and technology.

“Some of the laboratory and tissue pathology testing that we make available here is not offered anywhere else in the world,” he says.

Precise diagnosis is essential to determining the best options for treatment, Pestronk emphasizes. Many patients with muscle and nerve diseases come to the clinic with no cause that doctors can identify. Finding the genetic, immune or environmental factors responsible is the first step toward developing a treatment.

“Alan is one of the premier academic clinical neurologists in the area of neuromuscular disease in the world,” says David Holtzman, MD, the Andrew B. and Gretchen P. Jones Professor and head of Neurology. “He has developed numerous different novel blood tests that are useful in the diagnosis of a variety of disorders, and his website is one of the most utilized neurology websites worldwide.”

Tracing his own roots

An Australian neuromuscular fellow who helped Pestronk treat his wife became a good friend and contacted him two years later.

“He said, if you ever come to Australia, we have a special woman for you to meet,” Pestronk says. “Two years later, I went to Australia for a meeting and to visit him, and he introduced me to Lisa, and he was right.”

Pestronk went to Australia five times that year, and he and Lisa, a horticulturalist, married on his fourth visit. Pestronk’s family now includes seven stepchildren: Suzanne, Richard, Jill and Gabrielle Edison, from his marriage to first wife, Ilene; and Benjamin, Joshua and Daniel Kandy, from his marriage to Lisa. His father and mother, both 90, live in New York.

Pestronk’s cultural interests include dance. The New York City Ballet is his favorite dance company, and he served on the board of Dance St. Louis.

A good hometown Major League Baseball team also is a requirement for Pestronk, who grew up in New York enjoying Yankees games and lived in Baltimore during a successful era of Orioles baseball. Now, of course, he is a St. Louis Cardinals fan.

Pestronk says his “real hobby” is genealogy. He has assembled family trees for himself and the families of his two wives that include more than 7,000 people, and he is tracing the origins of his family’s name using personal contacts, genetic testing and historical records.

“In the original Polish and Yiddish, it’s Pistrong, which means trout,” he says. “It appears to date back to around 1780, when Jews in Poland were required to take surnames to make taxation and conscription easier. I’ve traced it back to a single male ancestor in a small town in southern Poland called Radomysl Wielki.”

Fast facts about Alan Pestronk

Born in: Cambridge, Mass.

Grew up in: Long Beach, N.Y.

Age: 64

Lives in: Clayton

Came to WUSTL in: 1989

Reason for coming: a “perfect job,” director of the Neuromuscular Division

Favorite dish to eat: wife Lisa’s chicken soup

Secret ingredient of the soup: chicken feet

Favorite dishes to cook: Baltimore-style crabcakes or pasta with white clam sauce