Bob Deusinger has always been interested in how things work. As a child, he entertained himself by putting things together, taking them apart and putting them together again. He was curious and industrious.

“I remember when I was around 10 years old, I went to a salvage yard and found an old bike frame,” he says. “I saved some money, bought parts and essentially built the bike,” he says.

That love of mechanics, coupled with an affinity for science and curiosity into how the human body moves, led him to earn a doctorate in biomechanics from the University of Iowa and to a successful career as a physical therapist for more than 30 years at the School of Medicine.

Deusinger, Ph.D., associate professor of physical therapy and director of the Human Biodynamics Laboratory, grew up in New Jersey, the second of four boys. Always athletic, he and a friend built a set of parallel bars while in junior high and practiced all summer until they were able to do handstands.

Since his high school didn’t have a gymnastics team, Deusinger competed in football, wrestling, baseball and track and field, holding the school record for the quarter mile.

Developing an interest

Deusinger was the first in his extended and immediate family to attend college.

“I went to college because many of my high-school friends did,” he says. “I really liked chemistry and biology. That, along with my interest in physics and mechanics, eventually led me toward physical therapy and bioengineering,” he says.

As an undergraduate at Slippery Rock College in Pennsylvania, Deusinger competed on the gymnastics team and taught gymnastics to individuals with disabilities. While pursuing a master’s degree in biomechanics at the University of Massachusetts, he took a course in adaptive physical activities for people with disabilities.

“I wondered if the application of mechanical principles could help to understand how people with physical limitations, disease and injury are able to move and still perform everyday activities,” he says.

Deusinger identified where he wanted to study to become a physical therapist and found a U.S. Navy program that would provide the financial support.

“I put all my eggs in one basket,” he says. “I applied only to the Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons program and for the U.S. Navy National Scientific Scholarship Program.” He was accepted into both programs in 1968.

After earning a degree, Deusinger began his Navy service as a physical therapist at the National Naval Medical Center in Washington, D.C. He was transferred to Camp Lejeune, N.C., where he became the director of the physical therapy clinic.

Most of the patients he treated had musculoskeletal injuries from training in the sand and the pothole-filled terrain along the North Carolina coast. He would treat the patients for a limited time, only to see them return again because it took longer to fully develop the necessary strength and body mechanics than was allowed by military guidelines, he says.

While that was frustrating, Deusinger had a revelation while working in Camp Lejeune’s emergency department, where many orthopedic injuries and pain problems were addressed.

“I observed musculoskeletal problems in the emergency room that could be helped with physical therapy,” he says. “I also recognized how much I didn’t know and how much more there was to learn about human movement.

“I was interested in combining an understanding of human movement with my engineering background in biomechanics,” he says. “The University of Iowa’s engineering department and graduate program in physical therapy had a collaborative relationship, which provided the avenue to connect the two things I wanted to blend.”

While working on his doctorate at Iowa, Deusinger went to Buffalo, N.Y., and worked with Steve Rose, Ph.D., who subsequently was recruited to Washington University to direct the physical therapy program here. He immediately recruited Deusinger to Washington University.

“I came here because I wanted to be in a more rigorous and dynamic academic environment,” Deusinger says. He assisted in upgrading the curriculum and taught kinesiomechanics for many years.

During his initial years as a faculty member, the Program in Physical Therapy only provided contract physical therapy services.

“I liked what I was doing in research and teaching,” he says, “but I felt like I needed to grow professionally outside academia.”

Creating a practice

Deusinger left his full-time position for a few years to practice, while still teaching a night course in what was then a master’s program. During the late 1980s, Deusinger started two clinics in the area, one for a rehab services company and one of his own. The experience served him and WUSTL well. In the early 1990s, he was asked to help start a practice for the Program in Physical Therapy.

“We established a small clinical practice a block from the 4444 Forest Park building with the idea of doing clinical research as well,” he says. “That’s where I started some of my initial knee injury research.”

“Bob had a vision for how research, education and practice could be integrated from the time he arrived at Washington University,” says Susie Deusinger, Ph.D., professor and director of the Program in Physical Therapy. “He’s had three main roles here over the past 30 years: to significantly upgrade physical therapy knowledge about biomechanics, to engage in research that was focused on understanding anterior cruciate ligament injury and osteoarthritis mechanics, and to build a physical therapy clinical practice.

“In his humble and persistent way, he’s excelled in each of these roles,” she says.

In 2001, the Program in Physical Therapy started the Washington University Physical Therapy Clinics in the 4444 Forest Park building.

“When we started, we had only about 150 patients and billed less than 1,000 visits the first year,” he says.

Over six years, Deusinger and his colleagues built the practice to more than 15,000 visits per year.

“Our clinical practice models that of the other clinical departments at the medical school. We’re very unique in that regard among physical therapy practices,” he says.

“We provide excellent clinical care to our patients as well as education for our doctoral students and clinical fellows and a research venue for many of our faculty,” he says. “We have so many freedoms here, which allow us to think beyond the normal to move things forward. There are some wonderful collaborative opportunities here at Washington University that wouldn’t be available anywhere else.”

Reaching a goal

One of those collaborations allowed Deusinger to fulfill a career goal he identified some 40 years ago. Working with Barnes-Jewish Hospital and faculty from the Division of Emergency Medicine and the Program in Physical Therapy, Deusinger implemented physical therapy services in the Barnes-Jewish Hospital Emergency Department.

“To me, being able to implement this area of physical therapy practice was like having a dream fulfilled — not too many people get to do that,” he says. “I knew there were a lot of things that physical therapists could do in an emergency department, and this was an incredible opportunity to demonstrate that.”

“Bob is a person of remarkable energy and optimism,” says Lawrence Lewis, M.D., associate professor of emergency medicine. “He is one of those rare individuals who is truly gifted in all three areas of the academic clinician — clinical practice, teaching and research — and has terrific administrative and managerial skills to boot. I am energized whenever I get the opportunity to work with him.”

In 2007, Deusinger stepped down from managing the physical therapy clinics to focus more on studying anterior cruciate ligament injury mechanisms and osteoarthritis.

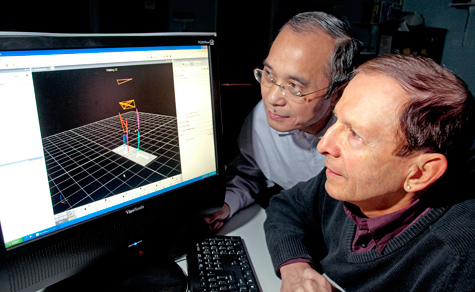

“Our hypothesis is that knee articular cartilage becomes less elastic as osteoarthritis develops and progresses,” he says. “We believe we can demonstrate this using a computational knee model. This could provide a way to detect the onset of osteoarthritis at a much earlier stage than is now possible,” he says.

Deusinger loves his work and doesn’t see retirement in the immediate future.

“I could be here for 20 more years,” he laughs. “Every time you do a research study, more questions arise and it takes you down another road. That’s what’s so exciting about doing research. Unanswered questions get my adrenaline flowing, and there are a lot of unanswered questions out there.”

Fast facts about Bob Deusinger

Hobbies: Dancing and listening to bands, including Dr. Zhivegas, in which his son Chris plays saxophone. “Susie and I enjoy going out together on Friday nights,” he says. “We usually go to J. Buck’s downtown.” He also plays basketball with undergraduate students and faculty at the Danforth Campus.

Family: Wife, Susie Deusinger; three children: Leigh, who works on the Danforth Campus; Chris, a professional musician; and Marc, who works at Enterprise Leasing. He also has two grandchildren: Sophie, 5, and Ava, 2½.

Reading: Investment publications and advisories. “I like to keep up with developing biotechnology and other technology industries,” he says.