Robert Boston

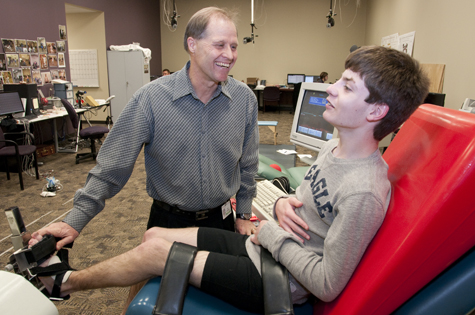

Jack Engsberg, PhD (left), associate professor of occupational therapy and of neurosurgery, with patient Alex Russo using an isokinetic dynamometer to strengthen Russo’s ankle. Engsberg and colleagues were among the first to show that increasing the ankle strength of children with cerebral palsy helped muscle spasticity.

In the early 1970s, Jack Engsberg thought his career path would involve sailing over a bar high above a mat.

As a champion pole-vaulter in high school and college, Engsberg wanted to coach track and field, with an emphasis on pole vaulting. Little did he know that the path would take a detour to Canada and he would settle in St. Louis, using virtual reality as a treatment for patients with cerebral palsy and those recovering from strokes.

Engsberg, PhD, associate professor of occupational therapy and of neurosurgery, grew up in Lake Mills, Wis., home to about 2,500 people. After graduating from the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse with a degree in mathematics, he taught math and coached track at Wisconsin Dells High School for six years. He then went back to UW-La Crosse to pursue a master’s degree.

“While I was there, I thought I wanted to be a track-and-field coach,” he says. “I wanted to learn about the mechanics of athletics, or biomechanics as it’s called, so I went on to the University of Iowa for my PhD, thinking I would go back to La Crosse and be the track coach. But I finally figured out that they weren’t teaching me to be a track coach — they were teaching me to be a scientist.”

That was all right with Engsberg. He figured he’d be a sports scientist and help elite athletes become even better and took a job at the University of Denver.

Unfortunately, Engsberg found out it’s difficult to find research support as a sports scientist.

“Every four years, the U.S. Olympic Training Center provided research funds, but for the other three years, there was nothing,” he says.

Changing focus

In 1987, Engsberg took a job at the University of Calgary in preparation for the 1988 Winter Olympics. He was thrilled that the position was 100 percent research — with one caveat.

“I was told I could spend 50 percent of my time doing whatever I wanted in research but then had to spend 50 percent of my time working with children who had leg amputations from the knee down,” he says.

At the end of the first year, Engsberg was spending 10 percent of his time on athletic research and 90 percent of his time with amputees. Eventually, he dropped the sports research completely.

Calgary was beginning to feel like home for Engsberg and his wife, Sue Grimston, PhD, who now works as a research assistant in the lab of Roberto Civitelli, MD, the Sydney M. and Stella H. Schoenberg Professor of Medicine, and plans were under way to build a house.

But a phone call from T. S. Park, MD, the Shi H. Huang Professor of Neurological Surgery and the chief of the Division of Pediatric Neurosurgery at Washington University, changed everything.

“He told me he was opening a lab to study the gaits of children with cerebral palsy (CP) at St. Louis Children’s Hospital and asked if I’d be interested in applying,” Engsberg says. “I told him I was quite happy in Calgary and wasn’t interested, and he asked, ‘Well, could you tell us what would go in a laboratory like this?’”

Engsberg sent Park a wish list of everything that should go in the lab.

“He came back and said ‘OK, we’ll give you all this. Will you come now?’” Engsberg laughs.

That was in 1993. He spent the next several years directing the gait lab in the WUSTL Department of Neurosurgery, working with Park’s patients with CP who had selective dorsal rhizotomy (SDR), a neurosurgical procedure that reduces spasticity and improves walking and standing in children or adults who have cerebral palsy.

In 2005, he briefly left the university but returned in 2007 as an associate professor in the Program in Occupational Therapy.

“Jack Engsberg is a treasure,” says Carolyn Baum, PhD, the Elias Michael Director of the Program in Occupational Therapy and professor of occupational therapy and of neurology. “He is a fine scientist, a great teacher and a wonderful mentor for the faculty and graduate students.”

Finding virtual reality

At his lab, Engsberg still works with patients with CP. He and his colleagues were among the first to propose that increasing strength, particularly in the ankle, could functionally improve movement in children with CP, but it was met with some opposition.

“In the past, conventional thinking suggested that by strengthening muscles, spasticity would be increased and the child worse off, so nobody was willing to fund us,” he says.

After convincing a National Institutes of Health committee that this was a viable theory, Engsberg received funding for a pilot study to test whether strengthening ankle muscles improves function. The results look promising, and research is continuing.

Perhaps the most exciting part of Engsberg’s research involves using virtual reality during therapy.

“We essentially play video games,” he says.

He has been working with Caitlin Kelleher, PhD, assistant professor of computer science and engineering on the Danforth Campus, to teach therapists to create customized games for clients.

For example, if a person needs to work on wrist strengthening and only can move the wrist back and forth 10 degrees, the game is modified to allow full-screen ability by using only those 10 degrees. As the range of motion improves, the game is modified further, allowing the participant to play any number of games with the ability he or she has.

Courtesy photo

The Engsberg family: (from left) Jack; daughter Katie, 16; wife, Susan Grimston; and son Christopher, 12.

“Current theories are that one must do hundreds of repetitions in order to improve, so what better way to do hundreds of repetitions than by playing a video game?” Engsberg says.

To test the theory that playing a game would encourage more repetitions, Engsberg and his team did a pilot study and found the participant did 1,000 repetitions during an hour and 20 minutes using the video game.

In addition to his research duties, Engsberg also teaches two classes — research methods and statistics. He also is the head of the new Rehabilitation and Participation Science (RAPS) doctoral program administered by the Program in Occupational Therapy.

“The students add a new dimension to my work,” he says. “They are so amazing and eager to learn.”

Fast facts about Jack Engsberg

Hometown: Lake Mills, Wis.

Highest jump in pole vault: 15 feet, 3 inches

Hobby: Makes furniture

Last book read: When the Game Is Over, It All Goes Back in the Box by John Ortberg

Favorite St. Louis restaurant: Bristol Seafood Grill

Other research projects: Working with Rosanne Naunheim, MD, associate professor of emergency medicine, to study how to safely remove people from a vehicle after an accident; and with Kerri Morgan, a doctoral student in the Program in Occupational Therapy, to study manual wheelchair propulsion