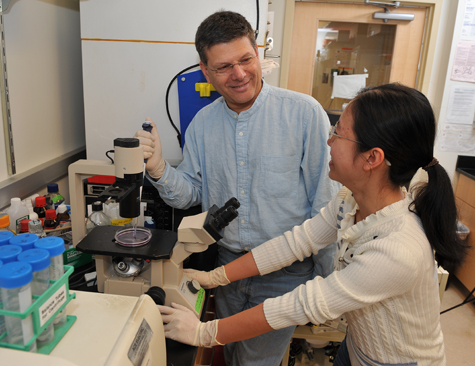

Ray Marklin

Raphael Kopan, PhD, professor of developmental biology, works in his lab with Shuang Chen, a graduate student in developmental biology. “He has high expectations, for himself and for others, and that shows in the quality of the work that comes out of his lab,” says David Ornitz, MD, PhD, the Alumni Endowed Professor of Developmental Biology.

Raphael Kopan, PhD, is addicted to discovery. Growing up on the outskirts of Tel Aviv, Israel, he discovered snakes, butterflies and bits of pottery native to an ancient land where a young immigrant community had settled.

“Our neighbors came from many places — Yemen, Poland, Germany, Russia. It was a diverse community,” Kopan says.

His parents, artists who came to Israel from Romania, encouraged their son’s penchant for discovery, giving him the freedom to roam the countryside. He collected snakes and watched them lay eggs. He kept scorpions that gave birth and cared for their young. He marveled at the fact that he often could read the Hebrew inscribed on some of the fragments of ancient pottery.

“It was a kid’s heaven,” he says.

To feed his addiction, he also read a lot, a habit that led the neighborhood kids to dub him “the professor.” Despite the nickname, as a child, Kopan didn’t consider becoming a scientist.

“I wanted to be an explorer,” Kopan says.

“When I grew older, I realized there was no place on the planet where a human hadn’t already set foot. So I turned to discovery of unknown facts. That’s a tremendous territory. There’s always room for new discoverers.”

Today, Kopan’s discoveries are made in his lab at Washington University in St. Louis. A professor of developmental biology at the School of Medicine, he works to understand how cells communicate.

Specifically, Kopan studies Notch, a protein that guides embryonic cells, which have the potential to become any cell type, into adult cells that do specific jobs, from producing insulin in the pancreas to transporting oxygen in the lungs.

Because it helps determine cell fate, Notch is instrumental in forming many of the body’s tissue types. As a result, researchers in Kopan’s lab have studied seemingly unrelated organs, describing Notch signaling in skin, kidney and lung cells.

“We feel we have a license to look at any developmental process in which Notch participates,” Kopan says. “But we don’t work alone. That our work is so diverse is a reflection of the collaborative environment at Washington University.”

Despite being basic scientists, many of his lab’s discoveries have proven clinically relevant. And since Notch guides cells into many tissue types, his lab has contributed to medical research across an array of disciplines, from Alzheimer’s disease to asthma to cancer.

From Lebanon to Kenya

Before settling on scientific research as his life’s work, Kopan served as an infantry lieutenant in the Israel Defense Forces.

“There was no question that we had to serve,” he says. “During the Six-Day War, I was too young. I spent time under a dining room table listening to shells going over our heads. There was a strong sense that it was the right thing to do, to serve your community before pursuing your personal goals. I went into the infantry because I love the outdoors; I didn’t want to be closed up in a tank.”

Kopan began his scientific career studying zoology at Tel Aviv University. He took every class that let him get outside, from field courses in entomology to Red Sea diving.

But, in 1982, world events interrupted his master’s studies. After a terrorist attack on a bus in northern Israel and an assassination attempt on an Israeli official in London, Israel prepared to invade Lebanon, and Kopan got his mobilization notice.

“At the time, I thought it was a saber-rattling exercise, and I prepared to be gone for a few days,” he says.

More than two months later, he returned after serving in Lebanon.

“I hadn’t set any process in motion to protect my experiments,” he says. “So there was nothing — no cells, no cultures. I came back to devastation in the lab.”

At about the same time, though, Kopan was presented with a zoologist’s dream opportunity.

“I got a phone call from a company that took academics to different parts of the world to guide tours,” he says. “If you were an art major, you went to Italy; if you were a zoologist, you went on safari in Kenya.”

Kopan calls it a wonderful experience. And though watching elephants and lions in the wild may not seem related to lab research, he says it honed his powers of observation.

“For the tourists, I would constantly describe what was going on — strategies for hunting, communication between predator and prey,” he says. “This training in observation continues to be relevant when you are observing at the molecular scale.”

The ghost in the room

Later, Kopan returned to Tel Aviv University and completed a master’s degree. But he also found himself frustrated with zoology’s traditional research methods.

“A good zoologist was supposed to be this ghost in the room. You could only observe,” he says. “You couldn’t manipulate the ecosystem. I became a developmental biologist because I could retain the connection to zoology, which I love, but I could test my observations by designing experiments.”

As he was completing a master’s degree, Kopan met the late Aron Muscona, PhD, a well-known biologist from the University of Chicago who was impressed with Kopan’s work. Muscona encouraged him to go to Chicago for his doctorate.

There, Kopan trained in the lab of Elaine Fuchs, PhD, an expert in the study of skin, including skin diseases and skin stem cells.

“Elaine made me into a true molecular biologist,” Kopan says.

He continued his training as a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of the late Harold “Hal” Weintraub, PhD, at the University of Washington in Seattle.

“It was a fantastic education — only part of it from Hal, a lot of it from colleagues,” he says. “You couldn’t escape with anything other than the most rigorous argument to prove your case.”

Kopan has brought that discipline to his own lab.

“He is one of the most rigorous scientists I know,” says Gregory Longmore, MD, professor of medicine and of cell biology and physiology.

Other colleagues agree.

Courtesy photo

To celebrate their 50th birthdays, Raphael Kopan (right) and his wife, Esther, climbed Japan’s Mount Fuji.

“He has high expectations, for himself and for others, and that shows in the quality of the work that comes out of his lab,” says David Ornitz, MD, PhD, the Alumni Endowed Professor of Developmental Biology.

Now, as Kopan ponders fresh ways to discover how cells do what they do, he is most excited about new techniques that draw from his zoology roots.

“We want to develop tools that will allow us to peek at these processes in living cells with the minimum amount of interference,” he says.

In other words, he wants to be the ghost in the room.

“If we can accomplish that, I think it will open doors to the next big questions.”

Fast facts about Raphael Kopan

Born: Petah Tikva, Israel

Family: Wife, Esther; and daughters Tal, 24, and Gili, 21

Hobbies: Motorcycles, woodworking, traveling, mountain climbing, reading and photography

Recent books read: The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson and Where Men Win Glory: The Odyssey of Pat Tillman by Jon Krakauer