From her perch high above the Meramec River, undergraduate Margo Crothers eyed the floodwaters warily. As a Pathfinder Fellow, she could remember camping overnight at a site near the river’s edge. Now that edge was gone.

“It looked like the forest was rising up from a lake,” Crothers said.

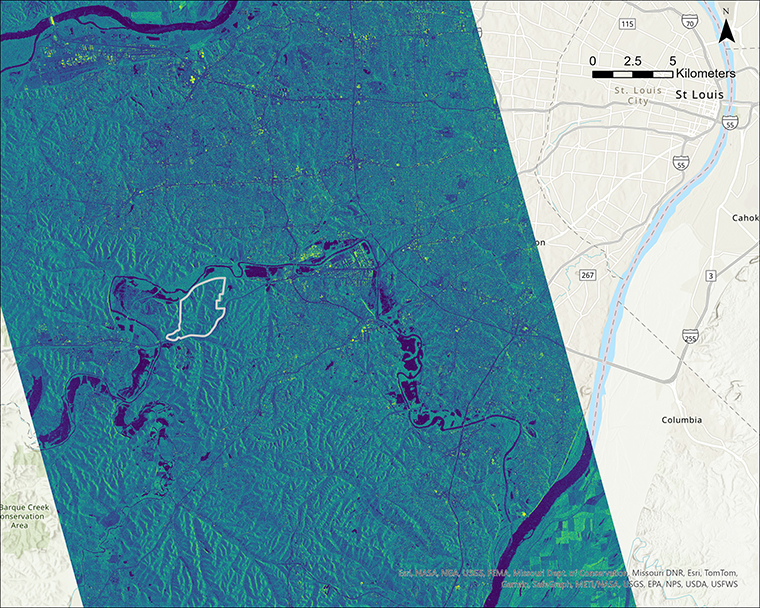

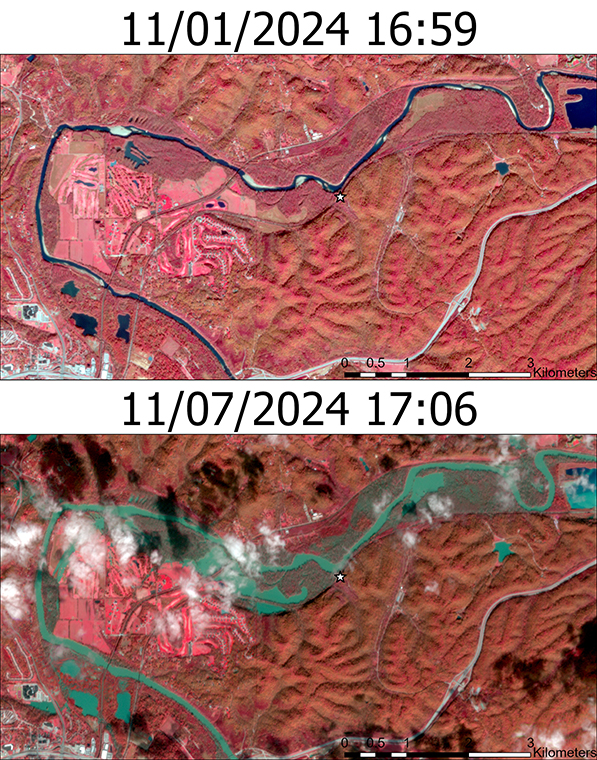

On Nov. 8, Crothers and classmates from her “Geospatial Field Methods” course (EEPS 468) traveled to Tyson Research Center, Washington University in St. Louis’ environmental field station, to collect high-resolution images of the Meramec River as its floodwaters crested.

Earlier in the week, a storm dumped up to 12 inches of rain on parts of eastern Missouri and the Ozarks. As predicted, after a few days’ lag, local waterways rose. Officials closed six Missouri state parks and other county parks and recreation areas as the high waters wreaked havoc along the Current, Jacks Fork and Meramec rivers.

As measured at the U.S. Geological Survey’s Eureka Gage, the Nov. 8 flood event was the 10th-largest flood of the Meramec River on record since 1904.

“When the flood happened, it was an opportunity to apply the course material to study a significant regional event in real time,” said Alex Bradley, an associate professor of earth, environmental and planetary sciences in Arts & Sciences and a director of the Geospatial Research Initiative at WashU, who co-teaches the geospatial class with Bill Winston, a geospatial technology specialist and programmer.

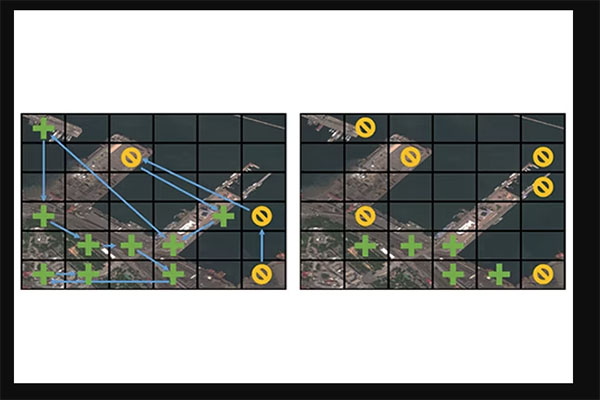

Students in the class learn how to make high-precision position measurements; how to collect and analyze light detection and ranging (lidar) data; and how to use drones to collect very high-resolution imagery.

For Crothers, an earth science major with a minor in math, both in Arts & Sciences, one of the most exciting parts of the day was the opportunity to fly the “big drone,” WashU’s newest unmanned aerial vehicle or UAV, a Quantum Trinity F90+, with a Micasense Altum-PT multispectral camera.

“We had to think about the whole process, and not just the small pieces,” Crothers said.

The sorts of data Crothers and her classmates collected at the Meramec River can be valuable in understanding the extent and damage of flooding and in assessing future risks.

Future redeployments of the WashU drone might help researchers observe how the landscape recovers from the flooding.

“This flood was large enough that we would expect there to be significant channel change in response to it,” said Claire Masteller, an assistant professor of earth, environmental and planetary sciences in Arts & Sciences, who also participated in the mapping excursion.

“Determining the extent of channel change from a flood of this size has important implications for infrastructure and river management, as this degree of inundation happens relatively frequently compared to the most extreme floods on record,” Masteller said. “We’d classify this event as a flood with a 10-year recurrence interval, or an event with a 10% probability of occurring each year.”

Crothers said that it took the class about an hour to fly the drone to survey this section of the Meramec River near Eureka, Mo.

Back on campus, the students will continue to work with the data that they collected over the next few weeks.

“One goal at the Meramec River was for students to get experience deploying these techniques in the real world in response to an emergent problem,” Bradley said.

“We learn technical skills on campus in a pretty controlled environment, but things can always go wrong in the field,” Bradley said. “EEPS students get a lot of practice at applying classroom skills to the real world.”