When Washington University Vice Chancellor for Research Jennifer K. Lodge first sounded the alarm about the disruptive impact COVID-19 likely would have on labs across the university, the research community heeded her warning, taking steps to shut down lab work and move as much as possible online.

Those in position to do so began pivoting their research to the novel coronavirus that has caused an unprecedented shutdown of public life across the globe. In a very short span of time, the university’s scientific community has responded to the pandemic with extraordinary research collaborations, all the while finding new ways to keep faculty, staff and students connected as they shift work out of the lab and into cyberspace.

“For all of us who are passionate about our research, we know that ramping down and pausing our work is very difficult,” said Lodge, professor of molecular microbiology who also serves as associate dean of research for the School of Medicine. “At the same time, this unusual situation may provide a rare opportunity for researchers to slow down our typically fast pace and think deeply about our science and connect with colleagues in ways we haven’t before.”

Scientific research is a complex endeavor, and figuring out how to slow or stop research that might involve living cells or mice is not a simple task. The Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research is constantly updating its coronavirus information website, “Guidance for Researchers on COVID-19,” and recommends that investigators frequently refresh the site to check for updates on the fast-changing advice and resources available to researchers, including updates from funding agencies, such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The office also has held virtual town hall meetings via Zoom to keep researchers up to date.

Sarah K. England, the Alan A. and Edith L. Wolff Professor of Medicine, has moved much of her lab online and set up a small, rotating group of people to take care of lab tasks that need to continue, even during a shutdown. England’s lab focuses on studies of the uterus and factors that might lead to preterm birth.

“We immediately made sure everyone has access to their data online, through Box, so that we all can work remotely,” England said. “Fortunately, quite a few people in my lab can focus on writing or new project planning. We still have a skeleton crew going into the lab to check on things we absolutely must check on. We set up an online calendar showing when people are going in so there’s no overlap and we can maintain safe physical distancing. It’s been helpful to have somebody there because we also were able to collect PPE to donate to coronavirus-focused clinical efforts.”

Farshid Guilak, professor of orthopedic surgery, described similar steps taken in his lab. Many labs, including his and England’s, are trying to maintain special colonies of mice. Even though active research may have stopped, it is important to continue caring for these groups of mice with special genetics and other characteristics that make them unique, so that work can ramp up again quickly when researchers are able to return to the lab. As a backup, researchers also have cryopreserved embryos of such specialized mice to ensure their survival.

“Fortunately, at this point, we are able to continue to feed our mice their special diets,” Guilak said. “We study models of obesity and how that might increase the risk of developing arthritis. We’re doing our best to minimize the impact of not having our typical access to the mice.”

The School of Medicine’s COVID-19 task force orchestrating research into the novel coronavirus is led by Jeffrey Milbrandt, MD, PhD, the James S. McDonnell Professor and head of the Department of Genetics; William G. Powderly, MD, the J. William Campbell Professor of Medicine and director of the Institute for Clinical and Translational Sciences (ICTS); and Sean Whelan, the Marvin A. Brennecke Distinguished Professor and head of the Department of Molecular Microbiology. A major focus of this work includes creating mouse models of COVID-19 infection and vaccine development.

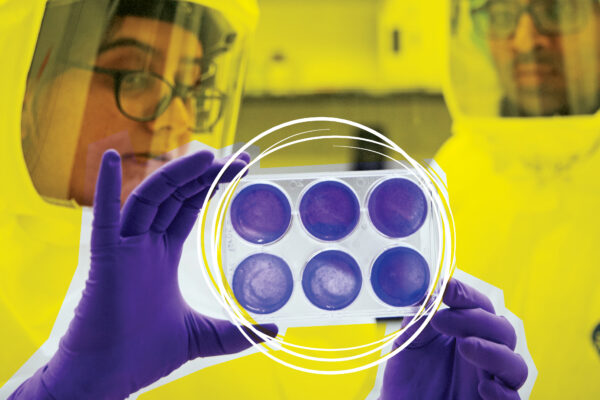

In addition, researchers who study other viruses, lung infections or have other related expertise are turning their lab’s resources to the novel coronavirus. Shabaana Khader, professor of molecular microbiology, studies tuberculosis (TB); and Jacco Boon, associate professor of medicine, is focused on influenza viruses. Both are uniquely positioned to trade research into one dangerous lung infection for another.

“Because we study other types of respiratory viruses, our lab is ideally equipped to conduct basic research on the COVID-19 virus,” Boon said. “We can grow the virus in our facility and, once we have animal models, we can start testing new compounds and antibodies for potential treatments. One challenge is that mice don’t have the lung receptor that this virus targets to infect human lungs. One solution could be to genetically modify mice to express the human lung receptor.”

Khader studies the lungs’ immune response to tuberculosis (TB) infection. Her team could, potentially, help shed light on how the immune system in the lungs reacts to coronavirus infection. As part of her TB research, Khader works with a collaborator at the Texas Biomedical Research Institute, Deepak Kaushal. Kaushal studies TB infection in macaques, nonhuman primates that have the lung receptor for COVID-19 infection.

“When we receive lung samples from his group, we will be using single cell technology to study the lung immunology of this disease,” Khader said. “We will be able to look at the immune response over time and how it might change from the first few days of infection to longer time points. So, my lab is shutting down our TB operations and ramping up COVID-19 work.”

Even investigators whose research might seem to have little to do with respiratory viruses are exploring aspects of COVID-19, such as investigating ways the pandemic is influencing childhood development. Deanna M. Barch, the Gregory P. Couch Professor and head of the Department of Psychological & Brain Sciences in Arts & Sciences, co-leads the Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development Study, a national study with multiple clinical sites involving a broad sample of children across the country. As much as possible, the study’s assessments have been moved online.

“We are adding assessments that directly address COVID-19 in terms of its impacts on families and kids,” Barch said. “We would like to understand what factors may predict resilience in this stressful situation and how that might impact brain development over time.”

Lori A. Setton, the Lucy and Stanley Lopata Distinguished Professor and chair of the Department of Biomedical Engineering at the McKelvey School of Engineering, said that several professors in her department also have pivoted their research to COVID-19, including studying the heart arrhythmia that some patients experience.

She also talked about supporting faculty members who are teaching online for the first time while ramping down work in their labs.

“I held drop-in coffee hours on Zoom, so faculty members could tell me what they needed to help with the transition,” Setton said. “Many lab groups are holding virtual ‘happy hours’ to have more casual discussions about their transitions to remote work and their research strategies moving forward. There are a lot of humorous and uplifting stories about these transitions that it has helped to share.”

Setton, Khader, England, Guilak and others also talked about the importance of maintaining social ties during this time of social distancing, and providing support for their lab members’ physical and mental well-being.

“Labs are little communities, and many of our trainees are far from home, so we’re concerned about everyone’s mental health,” Guilak said. “We’re trying to check in with everybody on a regular basis. We’re continuing our regular lab meetings online and then having smaller group meetings every week. Several of our trainees have started their own journal clubs. All of this is over Zoom or otherwise online, but it’s important to maintain the connections.”

Added England: “Many of our people have young children at home, and we’re trying to make sure everyone has the time and ability to adjust to the challenges of working from home for a while.”

Many labs and groups around campus have found ways to use Slack to stay connected. Guilak said his lab has a Slack channel called “Positivity,” where they share photos of kids and pets and trade recipes and cooking tips.

“I am inspired by the response of the Washington University community to this unprecedented situation,” Lodge said. “Thank you to those who have switched their work to COVID-19. And thank you to everyone who has taken steps to ramp down all other research in their labs and work remotely to keep as many people off campus as possible. Together, we are doing our best to bend the curve and help protect our clinical colleagues on the front lines fighting this virus.”

Washington University School of Medicine’s 1,500 faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is a leader in medical research, teaching and patient care, ranking among the top 10 medical schools in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.

Originally published by the School of Medicine.

WashU Response to COVID-19

Visit coronavirus.wustl.edu for the latest information about WashU updates and policies. See all stories related to COVID-19.