There is a name for the sort of math instruction Alexander Terrance got as a kid: Drill and kill.

“There was a lot of rote memorization, a lot of formulas, a lot of worksheets,” recalled Terrance, now the principal of Hoech Middle School in the Ritenour School District. “That was fine for some, but a lot of students grew up hating math. We didn’t think we were any good at it and we couldn’t see how this math stuff was going to matter in our lives.”

Terrance wanted better for his students. So he was eager to join Math314, WashU’s innovative program to boost math instruction and student achievement. For the past three years, instructional specialists from WashU’s Institute for School Partnership have partnered with Ritenour math teachers to develop better lessons and assessments. The results are promising. The percentage of middle school students in the district who score proficient or advanced in math has improved from 16% in 2021, the first year that Ritenour fully participated in Math314, to 24% in 2024. That represents a growth rate of 50%; the state average is 18%.

Equally important: Students report greater confidence and joy — yes, joy — in math.

“The work is challenging and collaborative. The students are learning to talk through a problem and explain their reasoning,” Terrance said. “You might think that as the rigor increases, the excitement would decrease. But it’s the opposite. When I ask kids, ‘What’s your favorite subject?’ I’m blown away by the number of students who say they really enjoy math now.”

ISP launched Math314 in 2019. At the time, 33% of the nation’s eighth graders were proficient in math, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Today, those numbers are even worse; only 28% meet proficiency standards. The reasons why are many and complex. But ISP was founded on the theory that every teacher can make a difference if provided the right tools and training.

ISP’s flagship program, the mySci curriculum, provides proof. Written by and for local teachers, mySci provides educators ongoing professional learning as well as the materials needed for engaging, hands-on science experiments. The result: mySci teachers report that they are better equipped to teach complex scientific concepts, and mySci students outperform their peers on standardized tests.

Math314, though not a curriculum, is a lot like mySci. Both programs help teachers identify and implement high-level tasks and use data to assess what’s working and what’s not. And like mySci, Math314 works in partnership with districts to meet their specific needs.

“None of this can be off the shelf because every district has its own challenges and its own demographics and is at a different starting place,” said Carmen Stayton, ISP’s director of Math314. “There is so much to do before we even step into a classroom.”

For a lot of districts, that work starts with adopting a high-quality, inquiry-based curriculum that meets Common Core state standards. Next comes the hard part: teaching teachers a new way to teach.

For a long time, math instruction has followed a “I do, we do, you do” protocol — the teacher shows students how to solve a problem and the students repeat the steps. Students who can quickly spit out the square root of 64 or divide 1/4 by 9/10 are deemed good at math and tracked for more advanced math, i.e. the sort of coursework that top colleges and science or technology employers look for in a candidate. Everyone else is left behind. Math314 instructional specialists know a lot of those students are — or can be — good at math.

“If you put together a room of the best mathematicians in the world and asked them to solve a problem, they would all find a different way to solve it,” said Vicki May, ISP’s executive director. “That’s why we do an inquiry process where there are multiple ways to approach a problem. The students learn to explain their mathematical reasoning and see the connections between their work and their neighbor’s work. Of course, students need to know their times tables because that sort of fluency makes you more confident. But Math314 goes a step further and helps kids gain a deeper, more flexible understanding of math concepts.”

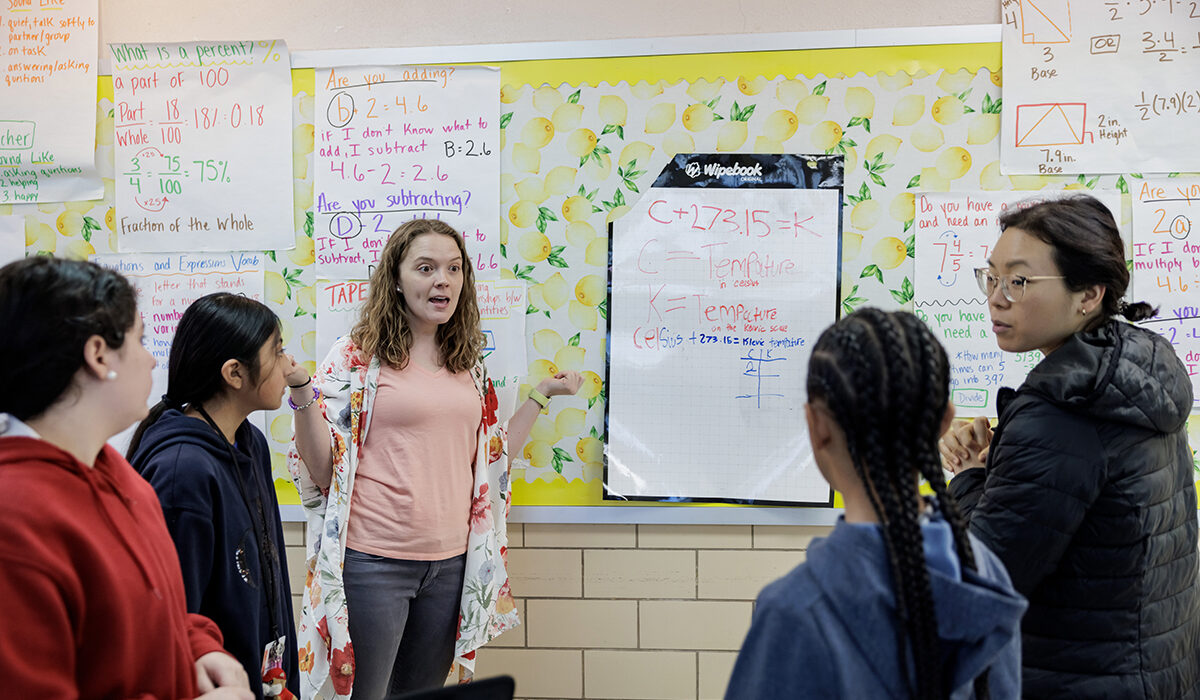

At Hoech, that means a planning period or “professional learning community (PLC)” meeting supported by ISP instructional specialist Jing Qiu on curriculum implementation as well as a PLC meeting facilitated by Hoech instructional coach LaTanya Buckner on instruction and data. On this day, eighth-grade teachers are analyzing, question by question, a recent assessment to see which concepts are stumping students. Yes, they agree, it looks like students are struggling with ordered pairs. They like the word problem in the book and develop a strategy to help the students visualize the question.

“At Ritenour Middle, the teachers were reflecting that because they spent so much time on systems, the functions unit flowed really nicely and kids were able to create equations for linear functions a lot faster,” Qiu tells the team. “So, yes, this is the unit to spend more time here.”

Eighth-grade teacher Stephanie Ratermann said these planning periods set Math314 apart from other professional learning programs. After 19 years in the classroom, she knows her stuff. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t more to learn.

“There is this misconception that once you write your lesson, you’re done,” Ratermann said. “But what worked in the past may not work today. You need to be responsive. And that’s where the PLCs come in. We talk about pacing, we talk about scaffolding, we talk about ways to make sure every student — no matter where they start — develops the ability to stick with a hard problem and the confidence to speak up in class.”

In addition to Ritenour, Math314 is working with educators in the Clayton, Hazelwood, Kirkwood, Mehlville, St. Charles, University City and Webster Groves school districts. Mehlville experienced the highest increase in MAP scores among all districts in the region, increasing by 7.5 points. Maplewood-Richmond Heights, which recently completed its partnership with Math314, was No. 2 in growth.

Located in St. Ann, Hoech Middle School serves about 650 middle school students. About 45% are Black, 26% are Hispanic, 16% are white and 10% are multiracial, and many are low income. When Terrance first arrived in 2022, some members of the Hoech community wondered if he should pause new academic initiatives until classroom behaviors improved. That would be a mistake, he argued.

“There can be a mentality that until behavior improves, academics can’t. But you can’t approach schools that way,” Terrance said. “And what we’ve seen is that Math314 has shifted the culture of those classrooms with behavior and academics progressing in tandem. That’s not to say we don’t have challenges — we do. But we have seen real growth. The students are more engaged; they are excited about math; they feel good about their teachers.”

Amos’ classroom affirms Terrance’s assessment. Today, she presents the sort of word problem that has vexed generations of children: Jada has a combination of 17 quarters and dimes. If Jada has $2, what combination of coins must Jada have? But first she creates a graph that plots all of the possibilities.

“What do we notice?” Amos asks. “Think about it and talk about it.”

The students turn to their neighbor and share their ideas.

“Both axes have a 17,” offers one student.

“Okay. That’s right. What else?” Amos asks.

“One end is 17, 0 and the other end is 17, 0,” offers another.

“OK, that’s important,” Amos says. “Keep talking. Y’all are smart. You can come up with it if you work together.”

After a few minutes, Guadalupe shouts out the answer.

“Oh, they all add up to 17,” she says.

“That’s right. Class, what’s 3 + 14? What’s 6 + 11? What’s 10 + 7? That’s right — they all equal 17. Everyone give up for Guadalupe,” Amos says, as the class claps.

Qiu gives Guadalupe a smile.

“I’ve really seen that class grow their confidence as mathematicians,” Qiu said after the class. “There were students who would not share, even when they had the right answer. Now you see an eagerness to try new things and talk about their solutions with their partners. Part of that is Monica — she is a really talented teacher that has very high expectations. But it’s also a result of this community we’ve built here where everyone — teachers and students — wants to grow.”