Washington University in St. Louis seniors Omar Abdelmoity and Marilee Karinshak were finalists for the Rhodes Scholarship, one of the globe’s highest academic honors.

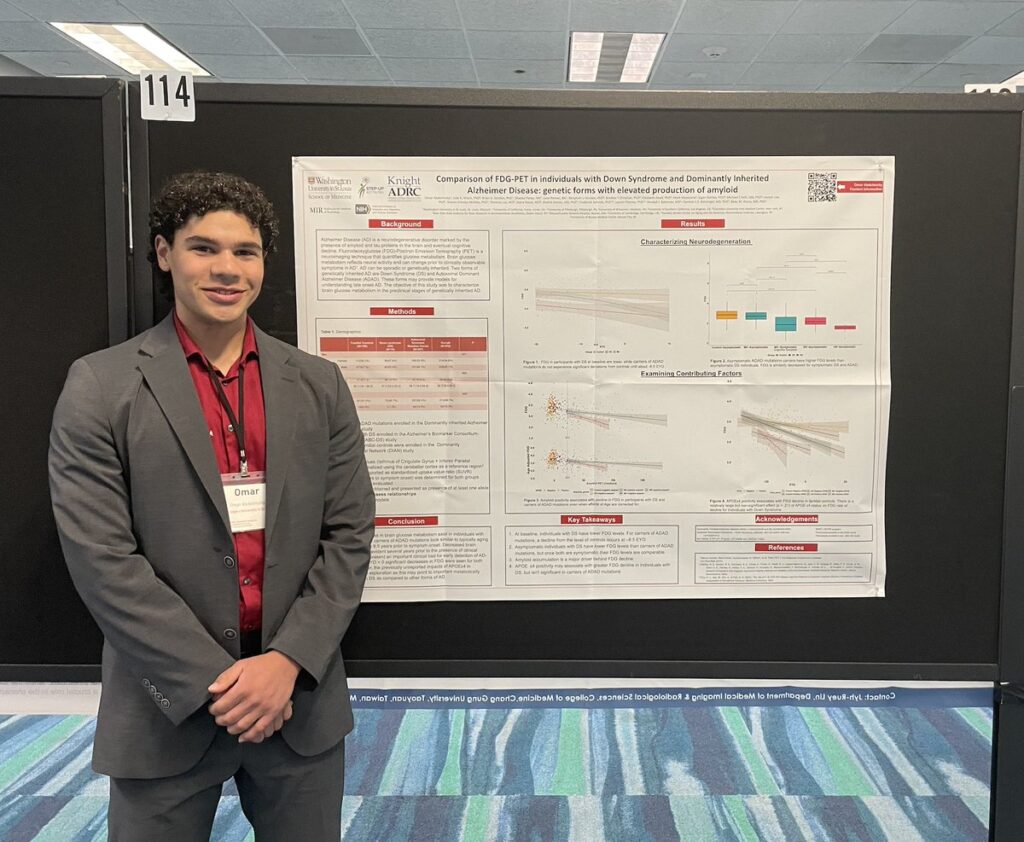

Abdelmoity, of the Kansas City suburb of Overland Park, Kan., is majoring in biology in Arts & Sciences and was recently awarded the Goldwater Scholarship, a national award that honors young researchers. He also is a finalist for the Marshall Scholarship, a prestigious award that funds graduate education in the United Kingdom.

Abdelmoity is a Medicine & Society Scholar and an Ervin Scholar. At WashU, he conducted groundbreaking research about the progression of Alzheimer’s disease in individuals with Down syndrome.

Ultimately, he hopes to earn his medical degree and support patients from underserved populations through research and policy advocacy.

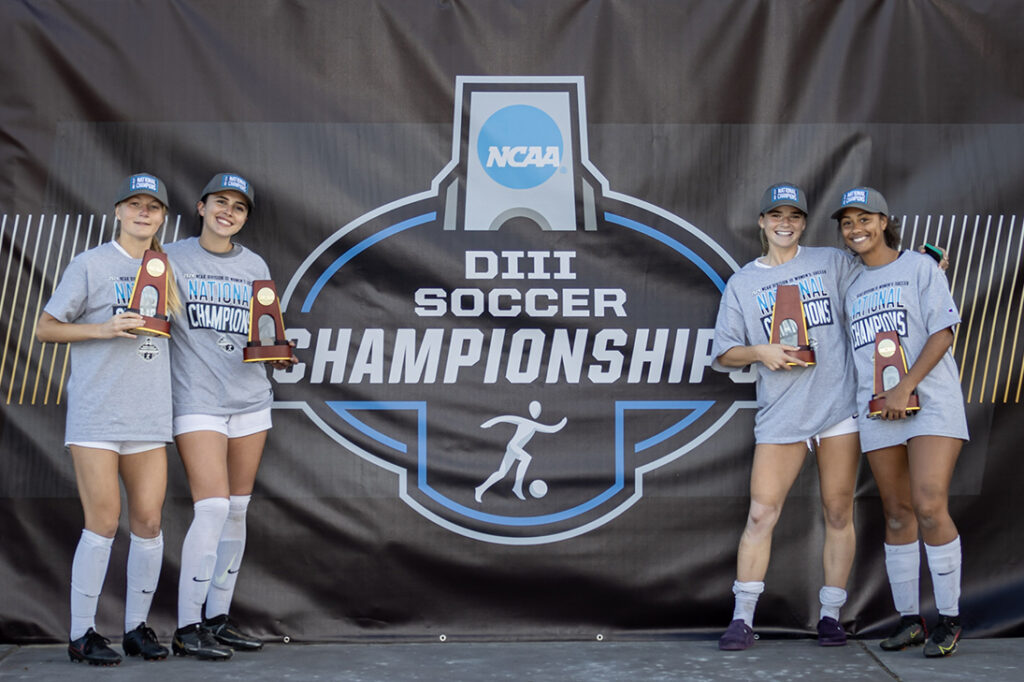

Karinshak of the Atlanta suburb of Lawrenceville, Ga. is majoring in environmental analysis in Arts & Sciences and also was a 2025 recipient of the Goldwater Scholarship. Karinshak also is co-captain of the WashU women’s soccer team, which won the 2024 Division III NCAA championship. Karinshak has completed two internships at NASA, where she used geospatial analysis to evaluate how pollution and climate change affect at-risk communities.

Karinshak aspires to study law to advance policies that protect environmental systems and promote community resilience.

Chancellor Andrew D. Martin praised Abdelmoity and Karinshak for their shared commitment to creating new knowledge in service of vulnerable populations.

“Omar and Marilee are both skilled scientists and talented communicators who have already made a meaningful impact in their respective fields,” Martin said. “I am confident that each will use their WashU educations to address the critical problems that they have identified.”

Serving the forgotten

To Abdelmoity, the seemingly disparate issues of suicide among Black youth and Alzheimer’s disease among individuals with Down syndrome reveal an uncomfortable truth — our medical system still struggles to meet the needs of those most at risk.

“There are people who will say, ‘Oh, it is what it is.’ I can’t accept that,” Abdelmoity said. “From my place in the world, humanity’s pressing challenge is its inequitable health systems — gaps that determine who receives care, whose suffering is prevented and whose voices shape science.”

Abdelmoity began studying youth mental health in high school after two friends in his soccer club died by suicide. He soon discovered suicide disproportionately impacted Black students like him.

“I started scratching my head about why there are disparities and asking how I can be part of the solution,” Abdelmoity said.

Abdelmoity joined the suicide prevention initiative Zero Reasons Why and developed a data-informed education program for middle school students that addressed the stigmas surrounding mental health and provided students coping strategies to support their own well-being as well as tools to help others in crisis. That work led to research opportunities at Children’s Mercy in Kansas City, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the Washington, D.C., Department of Behavioral Health — and an invitation to speak at the White House about suicide prevention.

“Expanding from my community to the national stage reinforced the same truth — service is strongest when it combines data, lived experience and the voices of those most affected,” said Abdelmoity, who was named a Future Leader in Psychiatry Scholar by the American Psychiatric Association.

At WashU, Abdelmoity has pursued research to benefit another underserved population: individuals with Down syndrome. As a National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded MARC U-STAR and NIH-STEP UP scholar in the Ances lab at WashU Medicine, Abdelmoity learned that people with Down syndrome are rarely included in clinical studies for Alzheimer’s disease despite suffering from the condition at a higher rate. He set out to study if Alzheimer’s progresses differently in this population and discovered that, yes, neurodegeneration often starts two decades before the onset of symptoms. Abdelmoity’s groundbreaking work was published in the Annals of Neurology and has led to new study protocols.

Beau Ances, MD, the Daniel J Brennan Professor of Neurology at WashU Medicine, said few students accomplish so much this early in their career.

“Omar’s work has clinically translatable relevance for individuals with Down syndrome, a population that has historically been marginalized and excluded from Alzheimer Disease clinical treatment,” Ances wrote in his recommendation to the Rhodes committee. “Through his work, he demonstrates the virtue of protection of the weak.”

Abdelmoity, a self-described science nerd, is taking his research one step further, partnering with a Spanish research institute to create the world’s largest APOE genotyped cohort of Down syndrome individuals to better understand the progression of Alzheimer’s disease in this population. The results of this novel study are to be published shortly with Abdelmoity as first author.

“One of the first things Dr. Ances told me is that we do this work not to publish papers but to inform our patient care,” Abdelmoity said. “The flip side is true as well. When patients come in with something we don’t understand, that informs the next research question we work on in the lab. It’s a never-ending cycle, and I love it.”

Turning insight into action

A former Tik-Tok producer, Karinshak was hired by NASA for her communications skills. But soon, she was conducting her own research, leveraging space-based technologies to track the changing climate.

“It’s amazing how data from above can show us what’s happening here on Earth and reveal things we didn’t know before, whether that be large-scale pollution dynamics or drought patterns,” Karinshak said.

As a geospatial analyst for NASA’s DEVELOP Program, Karinshak studied pollution patterns in Hampton Roads, a predominantly minority region and a major coal transportation hub. She discovered that the neighborhoods with the fewest resources had the highest levels of pollution. Yet despite the evidence, there was little she and scientists could do was to address the disparity.

“I realized that the real challenge wasn’t just in analyzing data, but in connecting it to policy decisions that would empower communities,” Karinshak said. “In that moment, I came to see that my work needed to live at that intersection — turning insight into action.”

Karinshak found that opportunity at the Data Analytics for Resources & Environments Centre in Australia, where she spent a semester at the University of Sydney. Using drone imagery and geospatial modeling, Karinshak

Karinshak assessed the health of local farmland and collaborated with farmers to develop interventions to rehydrate their land and make it more resilient to drought.

“They are the ones who know the land intimately, so it was essential that they be co-creators in the solution,” said Karinshak, who is now using the same technologies to track pests in the American soybean belt.

To Karinshak, this work is personal. Her great-grandfather died of black lung disease, and several of her relatives still live in Appalachia, which has experienced generations of environmental degradation.

“There are so many communities that are overwhelmed by environmental burdens,” Karinshak said. “The consequences to human health and the economy are devastating. But it’s important that we don’t create new vulnerabilities as we adapt to climate change. No community can be left behind.”

The same empathy and passion Karinshak brings to her research, she demonstrates in the locker room, said Jim Conlon, women’s soccer coach. He said Karinshak emerged as a team leader after a serious injury limited her playing time.

“This remarkable transformation from player to indispensable team motivator illustrates her unwavering dedication and exemplifies her ability to adapt and contribute significantly, even in the most challenging circumstances,” Conlon wrote in his recommendation letter to the Rhodes selection committee.

Indeed, Karinshak also sees science as a team sport.

“Creating good policy is all about listening and collaborating and being able to bring diverse perspectives toward a common goal,” Karinshak said. “In my heart, what keeps me invested in science and research is being able to bring people together so they can address the climate crisis in a way that serves their community. Everyone has a role to play.”