Earlier this month, the Internal Revenue Service reinterpreted a decades-old ban on political activity by religious organizations, known as the Johnson Amendment, now allowing churches and other houses of worship to endorse political candidates. The agency carved out the exemption — which did not include secular nonprofits — to resolve a lawsuit filed by two Texas churches and an association of Christian broadcasters.

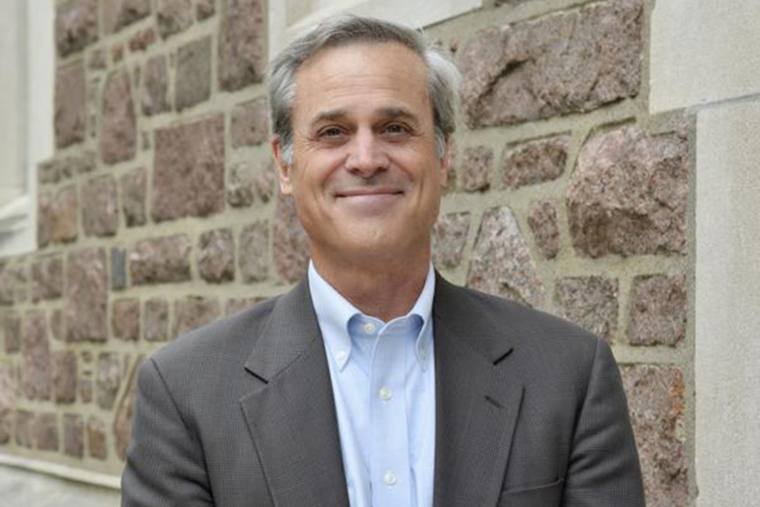

Although the settlement is being celebrated as a victory for Christian conservatives, Mark Valeri, an American religious historian at Washington University in St. Louis, warns that it will be disastrous for churches.

It also sets the stage for the U.S. government to favor religious groups that align themselves with particular politicians in a partisan manner, something the founders tried to protect against in the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause, he said.

“Even in a time when breaking precedents is the norm, this was stunning news,” said Valeri, the Reverend Priscilla Wood Neaves Distinguished Professor of Religion and Politics and vice director of the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at WashU.

“The Johnson Amendment of 1954 decreed that direct political advocacy, such as raising money for or endorsing political candidates, violated the charitable social service ‘contract’ that qualified these organizations to be tax-exempt.

“In practice, that meant that church leaders — pastors, ministers, rabbis, imams, priests — could not publicly advocate for named political candidates in a way that coerced or put religious pressure to vote one way or the other. They couldn’t threaten to excommunicate parishioners who didn’t vote for a particular candidate, for example.

“However, one could advocate moral causes that blended in the political issues. The Catholic Church, for example, has always said that abortion is wrong. There was a line between teaching moral positions that had political implications and directly using the church as an instrument for partisan political support,” he said.

Although that line between political advocacy and partisan politics was not officially drawn until 1954, it’s one churches have mostly observed since the early days of colonial America, Valeri explained.

“When the first colonial constitutions were written during the American Revolution, there was the assumption that churches wouldn’t be taxed. That precedent was established during medieval times. Still, in this age before the formation of political parties, most churches did not ally themselves with individual political leaders as representatives of a party.”

“Churches have always advocated for political causes, though. Pastors on both sides were vocal about the Civil War, for example. And Black churches were leaders of the Civil Rights Movement,” Valeri said.

Even so, this rule was not thoroughly enforced, Valeri said. Religious leaders learned in seminary that one doesn’t stand up at the pulpit at tell people how to vote. Most religious leaders understood and self-enforced as a matter of conscience.

Partisan politics divides churches

When the Johnson Amendment became law in 1954, in the middle of the Cold War, organized religions were enjoying a resurgence and increased prominence in American society. Religious affiliation peaked during the 1950s and ’60s and churches flourished, in part, because believing in God was seen as the antidote to the atheist, communist worldview.

‘If churches become identified with particular partisan political figures and parties, it will produce division and disharmony in churches and will alienate many Americans from religious institutions even further.’

Mark Valeri

“In the 1950s, churches were political, but not so much in a partisan way,” Valeri explained. “Churches were aligned along the lines of pro-democracy, liberal capitalism, First World against the communist world.”

Given the power churches held in the 1950s and the overall political consensus against communism, it made sense that political leaders wanted to put limits on political partisanship, and infighting within that consensus, Valeri said

“The Johnson Amendment did not mean that you couldn’t have a Sunday school class or a book reading group in a synagogue. You could still do that and talk about politics, and even sort of be pro-civil rights or, in some cases, anti-civil rights. You could have strong moral positions. But I think the notion was that explicit division into partisan political factors would break this American democratic alliance,” Valeri said.

American views of religion have shifted dramatically over the last 70 years. Although three in four Americans still identify with a religion today, less than half say religion is very important, and only 32% of Americans regularly attend church, according to Gallup polling.

Perhaps more alarming for religious leaders: Nearly 60% of Americans think churches are too concerned with money and power, and 54% agree that they are too involved with politics, according to a Pew Research Center poll earlier this year.

Valeri fears lifting the ban on partisan advocacy will encourage religions institutions to ally themselves with a particular political party. And that would have a disastrous effect on most churches, he said.

“If churches become identified with particular partisan political figures and parties, it will produce division and disharmony in churches and will alienate many Americans from religious institutions even further,” Valeri said. “That would be very problematic for churches.”

A slippery slope

Those fighting to overturn the Johnson Amendment have argued that the rule violated their First Amendment right to free speech, as well as the Free Exercise Clause, which prohibits the federal government from prohibiting free exercise of religion.

But Valeri said there’s another clause in the First Amendment that has been overlooked in the debate: the Establishment Clause, which prohibits the federal government from establishing state-sponsored churches.

“The people who are concerned about the Free Exercise Clause are more at ease with this, saying, ‘Why shouldn’t people be able to preach whatever they want to preach, including advocating candidate X, Y or Z?’” Valeri said. “But from the perspective of the Establishment Clause, this is very, very troubling.”

The Trump administration has delivered on many of its promises to religious conservatives, because religious conservatism has decidedly served Republican, right-wing politics, Valeri said. And the trend is not limited to the United States. Viktor Orban’s Hungary is an example of how conservative traditionalist religious views have been allied with authoritarian governments, he said.

“This latest move is encouraging a kind of Christian nationalism that is allied with the Republican Party and the president,” Valeri said. “This is something that the founders did not anticipate, and it should be a cause for concern for Americans who value the separation of church and state.”