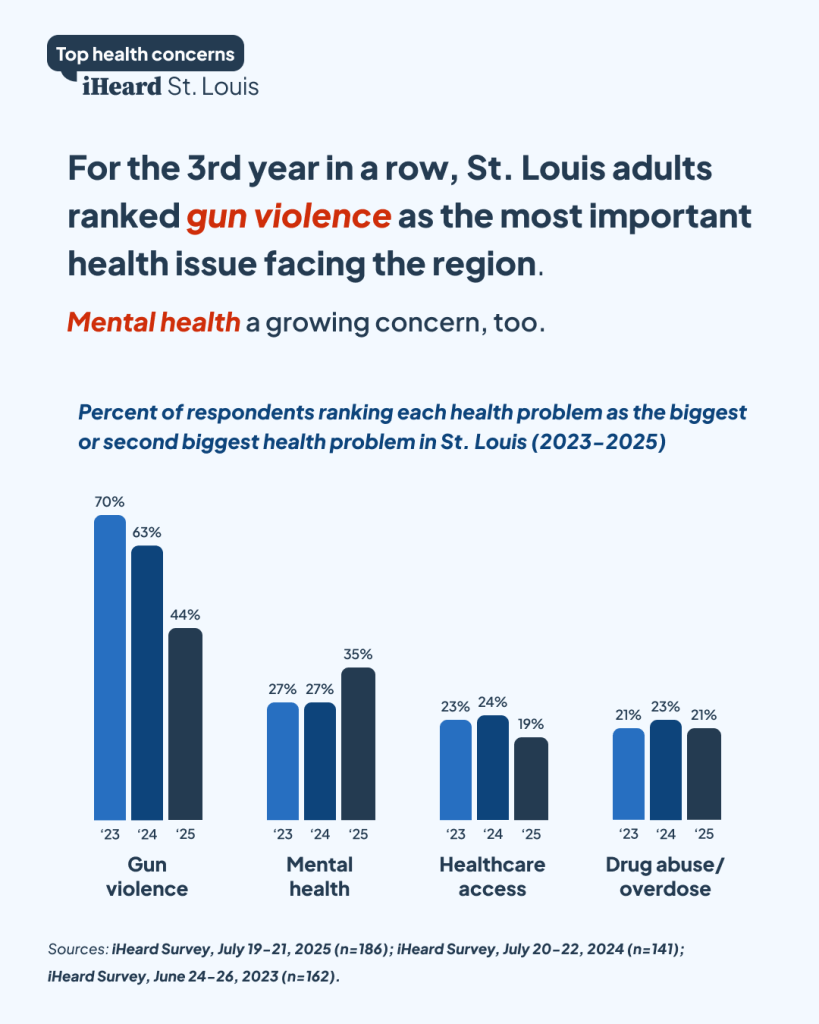

For the third year in a row, St. Louisans identified gun violence as the region’s leading health concern. But new findings from iHeard St. Louis — a program of the Health Communication Research Laboratory at Washington University’s School of Public Health — reveal growing attention to mental health.

The data comes from iHeard’s annual July poll of adults in St. Louis and St. Louis County. Each year, residents are asked to choose the biggest health problems facing the region from a list of 21 issues, with the option to write in additional responses.

While gun violence still tops the list, the percentage of respondents citing it has dropped — from 70% in 2023 to 44% this year. At the same time, urgency around mental health continues to build, with 35% naming it as a leading issue — up from 27% in each of the past two years.

For the first time, drug abuse and overdose ranked among the top three concerns, selected by 21% of respondents.

Food insecurity, newly added to the poll this year, was cited by 8% of residents — reflecting greater awareness of hunger and access to nutritious food.

“The rise of mental health as a major concern among St. Louisans is unmistakable,” said Matthew W. Kreuter, founder of iHeard and the Kahn Family Professor of Public Health at WashU. “When you combine that with concerns about drug addiction, abuse and overdose, it says a lot about what local community members think our health priorities should be.”

Following several devastating tornadoes, 6% of respondents named extreme weather as a top concern. Cancer, which had ranked in previous years, fell from the top 10 entirely, possibly reflecting alarm over more immediate threats such as violence, addiction and natural disasters.

These were the 10 most commonly cited health issues in this year’s poll:

- Gun violence (44%)

- Mental health (35%)

- Drug abuse/overdose (21%)

- Health care access (19%)

- Obesity (11%)

- Food insecurity (8%)

- Heart disease (7%)

- Traffic safety (7%)

- Extreme weather (6%)

- Diabetes (6%)

The July 19-21 survey included 188 adults from St. Louis and St. Louis County, with a 90% response rate. Participants are part of the iHeard panel — a standing group of more than 200 residents who voluntarily respond to weekly mobile phone surveys about local health issues.

Now in its fourth year, this panel offers a consistent, week-by-week view into what St. Louisans are hearing, believing and prioritizing about their health. This structure allows researchers to track shifts in public opinion with strong reliability. iHeard also surveys panelists in Georgia, Mississippi, Nebraska and North Carolina.

What is iHeard St. Louis?

Building health knowledge and trust in communities is one of the most urgent challenges facing public health today — and iHeard St. Louis is helping lead an evidence-based response.

Launched during the COVID-19 pandemic, iHeard initially helped health officials respond more quickly to vaccine misinformation. Since then, the program has broadened its scope. It has been supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding and expanded to seven states. St. Louis is the national hub for survey development, data analysis and message creation.

iHeard’s listening-first model starts with an environmental scan team at WashU that tracks headlines and social media to identify emerging health issues.

To better understand public knowledge, beliefs, questions and concerns, the team polls residents weekly on both trending headlines and enduring health issues, such as: Are black cooking utensils safe? Is fluoride in water dangerous? What are the most common heart attack symptoms?

Based on those findings, the team produces infographics, alerts and social media assets, which are shared with more than 200 community organizations in St. Louis, including health departments, to provide factual information quickly and widely.

“We usually think of health exposures as some toxin or virus or maybe cigarette smoke over many years,” Kreuter said. “But information is also an exposure — both accurate and inaccurate information. The way we’ve thought about exposure to misinformation in public health has been a little too simplistic — like you were exposed or not exposed to a false claim. What we’re finding is that some people get exposed to misinformation again and again.

“And if public health is going to be in the fight to build accurate health knowledge, it’s going to have to mount a sustained response,” he added.