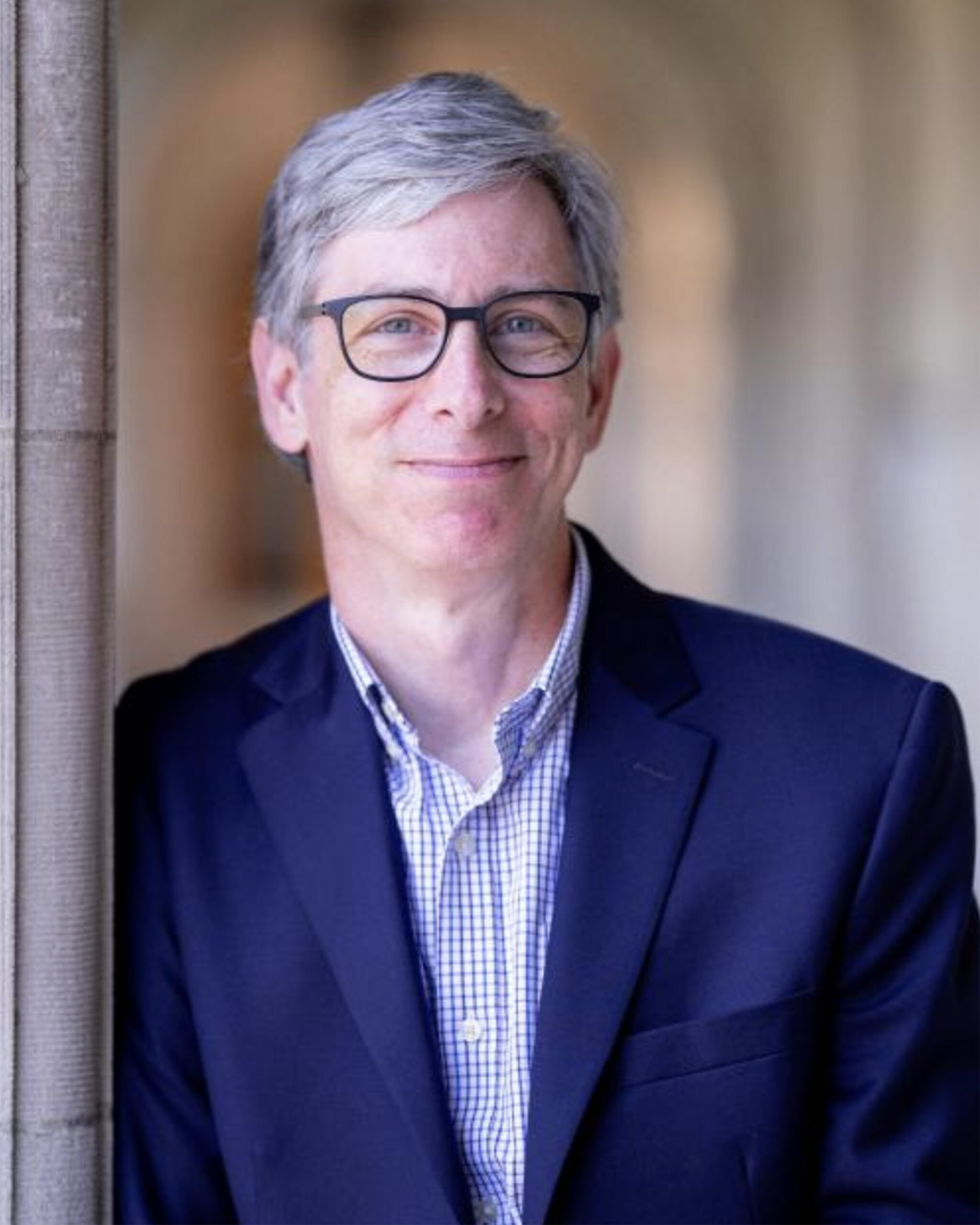

The Trump administration has placed federal agencies and federal employees at the center of national debate. For historian Peter Kastor, this raises a series of questions. How did that federal workforce come into being? What kind of government did the Founding Fathers claim they wanted? And what kind of government did they actually create?

Kastor, the Samuel K. Eddy Endowed Professor in history in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, has spent years collecting and digitizing records for 37,000 people who worked for the federal government between 1789 and 1829. The results are now publicly viewable via the “Creating a Federal Government” digital archive.

In this Q&A, Kastor discusses the project, the priorities of the early federal workforce and the nature of the confirmation process.

How did this project come about?

Like every historian, I wanted to tell a story that nobody had told before. But there’s another origin story, too.

My first job out of college was with the Justice Department, in the office that enforces the Voting Rights Act. In the run-up to the 1990 census, I saw how journalists were emphasizing the political, partisan dimensions of redistricting. And in many ways they were correct. But in other ways, they ignored the realities of governance — and the role of offices like ours in reviewing and, in some cases, redesigning election districts.

It became clear to me that there was an interesting story to tell about how government employees do their jobs. That includes what they’re directed to do by leadership, but also the ways that leadership is limited in its ability to get them to do it.

The classic organizational conundrum …

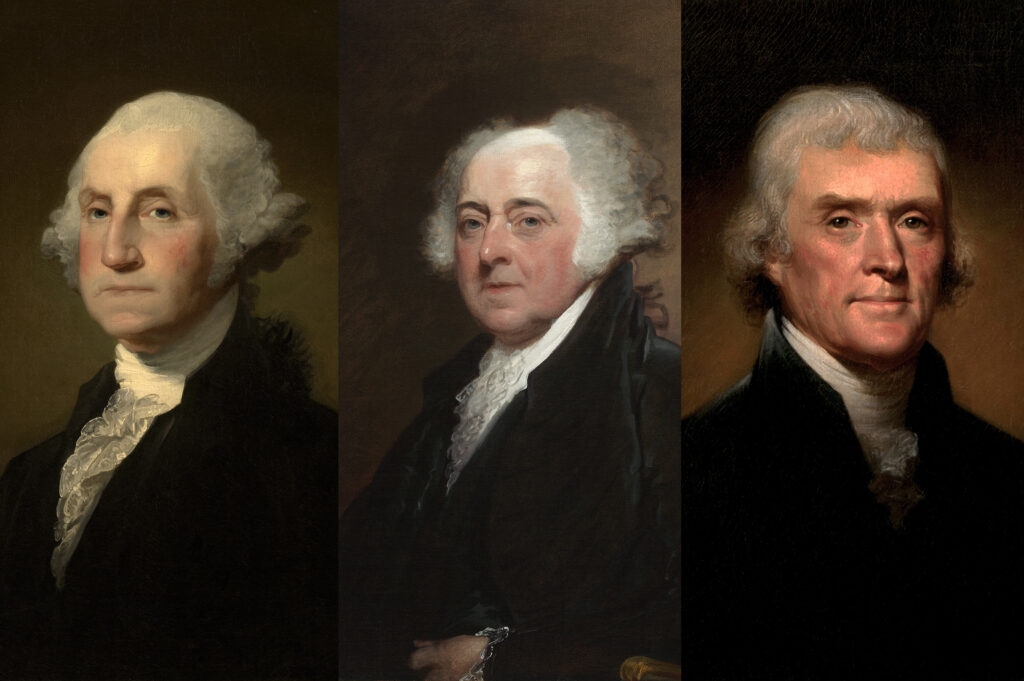

Absolutely. I’ve written about people like Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton and George Washington. But I found that a lot of the action was with mid- and lower-level officials. They had to implement the founders’ decisions without any direct mode of communication.

How did those officials respond?

With anxiety and autonomy.

Customs officials levy import duties on foreign goods. That’s tremendously important for federal revenues but puts them in the crosshairs of commerce and international diplomacy. They’re a cautious group.

Many higher-level officials — U.S. attorneys, territorial governors — had held elected office. They’re used to power. They’re more comfortable making decisions.

Was any of this material previously digitized?

A small amount. The State Department maintains a digital catalog of principal officers and chiefs of mission. During the time period I study, that’s a couple hundred people. The Federal Judicial Center — whose principal historian, Christine Lamberson (BA ’04), is a WashU alumna — maintains a wonderful database of federal judges. That’s another 140.

So who are the rest?

The largest number, around 15,000, are postmasters. In the 1960s, the National Archives created a preliminary inventory of postmasters — it’s a ledger with sheets of loose-leaf paper, much of the information handwritten. And beginning in 1816, a continuing resolution from Congress required the executive to produce, every two years, a list of all federal employees. So that’s every customs official, territorial official and commissioned officer in the U.S. military. These were tremendous sources, but none of their contents had been fully digitized.

You recruited dozens of students. How labor-intensive was digitization and transcription?

Very. This is a mix of typewritten and handwritten material. Optical character recognition software could not produce a reliable result.

Another challenge was disambiguation. I’ve written about William Clark, who most people know from the Lewis and Clark expedition. But there are dozens of other William Clarks, and they show up in very idiosyncratic ways. Names are spelled differently. Nominations are described differently. We couldn’t get a computer to figure all that out.

The geospatial dimension was similar. Sometimes mapping was straightforward. But let’s say we’re looking at a St. Louis appointee. Existing software will place the dot for St. Louis at the geographic centroid of the city’s current boundaries — near the east end of Forest Park. In 1804, that wasn’t even farmland. It was the fringe of Osage country. So we had to establish the historic location of the city, which coincided with the current grounds of the Gateway Arch. We had to do the same thing with over a thousand cities, towns, neighborhoods and even individual buildings.

Clark is featured on the homepage, along with John Quincy Adams, Elizabeth Kelly and Thomas Melville. Why those four?

I wanted people who would exemplify the range of experiences in the federal workforce.

Clark is interesting. He was territorial governor of Missouri, which is a high-level office but not a cabinet position. Federal service was core to his identity as an American, but he definitely saw himself as a subordinate.

Adams is a familiar name. People know him as one president and the son of another. But he also spent decades as a diplomat. He’s a great example of people who served the federal government outside the United States, as well as the small number who achieved high-ranking political office.

Kelly was a nurse in a marine hospital in the 1820s. We don’t know where she was born or where she died. But she’s one of about 100 women in this collection. The largest number are postmasters. Most of the others served as nurses or, interestingly, as lighthouse keepers. She is a reminder that women served in the federal government from its earliest years, but also a reminder that their opportunities were profoundly limited. I also wanted to include her because I didn’t know when she was born or when she died. She’s a great example of the limits of what we know.

Melville was a Massachusetts revenue official. The Revenue Act of 1789 brought many state offices into the federal government. Melville had fought in the Revolution and, leveraging that, wrote to George Washington personally. Forty years later, he’s still there. It was a steady gig. Later, when his grandson, Herman, is trying to make it as a writer, he takes a day job is the New York customs house. He’s a great example of the long-serving, mid-level officials who were among the first federal employees.

What does this archive reveal about the nature of the early federal government?

The archive reveals how Americans experienced their government on a day-to-day basis. Certain offices were everywhere. Postmasters delivered mail state to state. Federal judges settled interstate conflicts. They showed that the union was real. They embodied the idea that as Americans, we’re all connected.

Once we get past that, most federal officials along the Eastern Seaboard are involved in revenue collection. Their job is to raise money. Most of that money gets spent in the West. It’s spent expanding freedom and eliminating freedom; promoting equality and eliminating equality.

How so?

The biggest domestic challenge for the federal government was converting the western domain into federal territories and then into states. That’s very costly. It takes a lot of people. And it’s premised on the notion that people who live there will become equal citizens.

Yet the federal government also remained fully invested in preserving slavery. And the majority of the U.S. Army is stationed in the West. In part, that’s due to concerns about the Spanish Empire, but it’s principally about Native American policy.

Your dataset includes 5,000 presidential nominees. What did you learn about the confirmation process?

Let’s start with how people requested nominations, because we have over 18,000 letters of application and recommendation to office. What was striking to me was that people framed their applications less in terms of party loyalty than national loyalty. They generally support the Constitution. They support the power of the executive. They support the independence of the other branches.

When it came time to determining how best to put people into office, George Washington set the tone and his successors didn’t question it. Statute required him to submit some offices to the Senate for advice and consent. He actually submitted many more. One time, he physically went into the Senate. He just showed up. The senators asked, what are you doing? Washington replied that he’d come to seek their advice and consent on a series of nominations. Senators were doubtful. They responded that Washington may have claimed he wanted their advice, but they thought he was demanding their consent.

To senators, Washington’s presence in the Senate chamber was an intrusion of the executive on the legislature. He never did it again. The senators’ concern made sense, but they were probably overreacting. Washington believed deeply in the separation of powers and in the checks and balances of advice and consent.

So senatorial confirmation wasn’t just some bureaucratic hurdle?

No. They never saw it that way. The early Senate approved nominations at a 90% rate. But like the earliest presidents, they believed that the process made manifest the notion of checks and balances. They felt that very strongly.

In many ways, this government was tremendously inefficient. When the secretary of the treasury was writing to individual customs collectors, that was inefficient. When the president was writing nominations by hand, that was inefficient. But they didn’t have any other way to do it. Put simply, they don’t have HR managers. They don’t have a bureaucratic structure.

But I think these stories transform our understanding of the founding era. The founders emerge as people who, yes, cared about high political theory. But they also cared about managing a government.