For years, scholars, advocates and journalists have highlighted the ongoing racism and segregation in the housing market, yet a segment of the housing market — government-subsidized housing — has been overlooked, until now.

A new study from researchers at Washington University in St. Louis and other institutions is the first in decades to investigate racial inequality in the subsidized housing market. Using restricted 2017 American Housing Survey data provided by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), researchers found quantitative evidence of widespread racial inequities in unit safety, total cost, affordability — defined as percent of income spent on rent — and segregation.

For example, they found that Latino subsidized renters pay $110 more per month than white subsidized renters — a 25% upcharge — despite living in lower-quality units. Black and Asian subsidized renters, on average, pay $75 more per month than their white counterparts — a 17% upcharge. For Latino and Asian renters, in particular, some of the total price difference is due to living in more expensive cities, but all three of these groups spend 5% more of their household income on their subsidized units than their white counterparts.

Only Indigenous subsidized renters pay less than white renters — a difference of $72 per month. However, both groups spend a comparable proportion of their household income on housing and Indigenous subsidized renters are more likely to live in lower-quality, unsafe units.

In short, Black and Latino subsidized renters live in units with more unsafe conditions while simultaneously paying more, both in total cost and relative to their income, researchers said. They also live in neighborhoods that are more racially isolated when compared with white subsidized renters and the housing market as a whole.

“Federally subsidized public housing is the most cost-effective and efficient way to ensure millions of Americans have access to affordable, safe housing — it is an essential safety net in the United States,” said Elizabeth Korver-Glenn, an assistant professor of sociology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University, and research co-author.

“However, our research shows that we still have work to do to reform and reinvent the program in a way that ensures equal access in compliance with fair housing legislation. The racial inequalities we found in the subsidized housing market are even greater than those in the private housing market.”

The study was first published online Aug. 26 in Socius, an open access journal published by the American Sociological Association.

Korver-Glenn and co-authors Junia Howell, a visiting assistant professor of sociology at the University of Illinois Chicago, and Ellen Whitehead, an assistant professor of sociology at Ball State University, hope the study will illuminate the stark inequities in the subsidized public housing program and spur additional research to identify specific interventions government agencies can take to promote equity and integration.

“It’s important to note that public housing, especially as originally conceived, is not the problem,” Howell said. “The problem is these benefits are still disproportionately afforded to white older adults while families of color are segregated into lower-quality, higher-cost units.”

How did we get here?

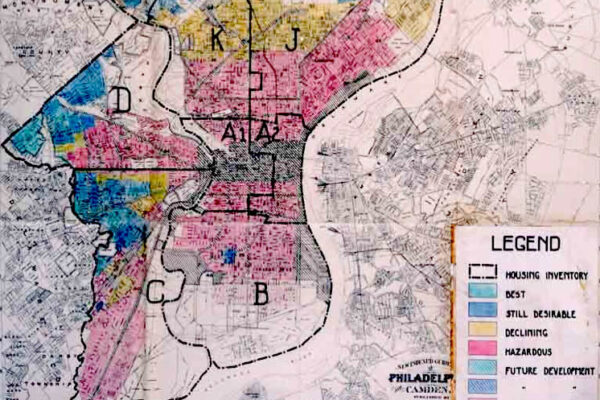

In the 1960s, activists pressured the federal government to address segregation and stark inequality in public housing leading to the passing of the 1968 Housing and Urban Development Act. But then, many white public housing complexes were sold to private companies that received federal funding but set their own — often racist — tenant eligibility requirements. Conversely, Black subsidized renters were disproportionately concentrated in publicly managed complexes, Howell explained.

“Within only a few years, public housing complexes went from being perceived as desirable, decent and affordable housing for ‘upstanding’ white families to being perceived as crime ridden, filthy and a last resort for families of color,” the authors wrote.

“Consequently, the public and the scholarly community ignored the fact that white renters remain the largest racial group among subsidized renters (42%) and failed to ask whether government-subsidized housing programs were now racially equal and integrated.”

Today, more than 10 million Americans — including seniors, veterans, those with disabilities and low-income families — receive federal rental assistance. Many of the practices that became commonplace after the passing of the 1968 Housing and Urban Development Act continue today.

In particular, researchers found a strong correlation between a renter’s race and the type of program they were filtered into.

- White renters are disproportionately concentrated in HUD-funded privately managed developments and other government subsidies. “Within private rental market, landlords’ racist stereotypes and practices segregate renters and provide higher quality housing and lower price points for white tenants,” the authors wrote.

- Black subsidized renters are still disproportionately concentrated in publicly managed complexes and the tenant voucher program, which is the most expensive of the housing subsidy programs for both the government and the residents, according to the authors.

- Latino tenants are more likely to live in other government-subsidized housing, such as migrant settlement housing or locally funded housing projects.

According to the authors, another reason why white subsidized renters continue to receive higher-quality units is because they tend to be older. By comparison, Indigenous, Asian, Black and Latino subsidized renters are disproportionately families with children. Most subsidized housing programs separate older adults from families, and the housing available to older adults is often well-maintained. This practice exacerbates inequities and racial segregation in subsidized housing, they said.

Could personal preferences be another cause?

“If personal preferences were a significant factor, racial inequality across low-income renters would be comparable for subsidized and unsubsidized tenants,” Whitehead said. “While the general racial inequality patterns are similar, racial inequality is notably larger for subsidized renters, which indicates that personal preferences are not a significant factor.”

Going forward

‘It is time for our government to once and for all close loopholes and adopt new practices that will ensure equitable and fair housing practices for all low-income subsidized renters. We can and must do better.’

Elizabeth Korver-Glenn

In the 1960s, calls to reform the federally subsidized public housing program led to a series of actions that demonized, privatized and slashed program funding. Howell said they hope this will serve as a lesson for today’s leaders.

Despite its flaws, HUD-funded project-based subsidies — those most criticized within public discourse — provide the highest quality, most affordable units for low-income tenants at the cheapest price point for the government, the authors wrote. And compared with unsubsidized low-income renters, subsidized renters live in safer conditions and spend less of their income on housing.

Further defunding governmental housing programs or increasing the number of tenant vouchers will not only fail to address the racial inequities outlined in this study, it would also be a travesty for millions of vulnerable Americans, the researchers said.

“It is time for our government to once and for all close loopholes and adopt new practices that will ensure equitable and fair housing practices for all low-income subsidized renters. We can and must do better,” Korver-Glenn said.