To much of the world, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s actions leading up to and since the invasion of Ukraine have often appeared unpredictable and illogical. For example, when faced with embarrassing military setbacks, Putin doubled down with a massive military mobilization rather than looking for an exit strategy — as most assumed he would do.

Russia’s recent retreat from Kherson had renewed hope among Ukrainians and Western allies. Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, has described the withdrawal as “the beginning of the end of the war.” Days later, on Nov. 15, Russian missiles struck three major Ukrainian cities.

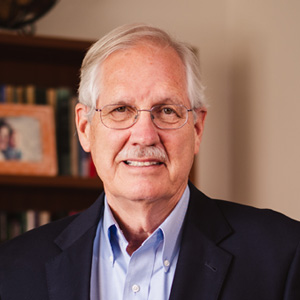

To avoid further surprise, Western leaders need to better grasp Putin’s worldview, which is heavily shaped by three basic national narratives, according to James Wertsch, the David R. Francis Distinguished Professor and director emeritus of the McDonnell International Scholars Academy at Washington University in St. Louis.

Putin has relied on these centuries-old narratives to convince Russians — and perhaps himself — that the war in Ukraine is worth fighting, according to Wertsch. Understanding these narratives could help the U.S. and NATO better anticipate Putin’s next steps. Even more, challenging the narrative might be the most effective way to beat Putin at his own propaganda war, he said.

“National narratives are very powerful and largely impervious to challenge from facts and rational argument,” Wertsch said. “What is needed instead are efforts to control the narrative and move it in a new direction. This is a daunting struggle in Putin’s Russia, where many opposition figures are in prison or in exile, though.

“The narratives at work are bigger than any individual. Any likely successor of Putin will probably adhere to the same core beliefs.”

A tale as old as time

The first national narrative — the threat of invasion by alien enemies — has long been a mainstay of Russia’s worldview, Wertsch said.

“Multiple stories tell of invaders that had to be crushed and of the great suffering and heroism involved. Russia has had plenty of practice at this,” Wertsch said.

From the Teutonic knights and the Mongols in the 13th century, to the French during the Napoleonic Wars of the 19th century and the Germans of the 20th century, Russia has no shortage of stories about alien invaders who were crushed thanks to the suffering and heroism of Russians, Wertsch said.

“The narrative habits around these past existential threats are now being applied to NATO and the West,” Wertsch said. “But when these habits are used to justify the Russian invasion of a sovereign nation like Ukraine, they have run amok and are counter to international norms and laws Russia itself has proclaimed.”

The second narrative that guides Putin is the story of how Russian civilization evolved during the past millennium to encompass other Slavic populations, especially Ukrainians, Wertsch said. In his 2021 article, “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians,” Putin argued that Ukraine has always been a part of “the same historical and spiritual space” as Russia and that the two peoples, cultures and languages are essentially the same.

“The implication is that Ukraine should revert to its natural historical role as part of ‘the single whole’ of Russia and accept that Russia was robbed of part of its organic estate and is just getting back what has always belonged to it,” Wertsch said.

While Putin relied on this narrative in the early, relatively peaceful stages of his efforts to reincorporate Ukraine — insisting that anyone who disagreed was either a Western enemy or brainwashed — it soon became apparent this effort was not having the impact Putin had hoped for in Ukraine, the West or even Russia, Wertsch said.

Enter the final — and perhaps most ominous — national narrative: Russia as the global champion of traditional values and pure Christianity against the “satanic” West with its corrosive ideas about liberal democracy. According to Wertsch, other national leaders, such as Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban and Chinese President Xi Jinping, advocate similar narratives, but Putin sees Russia as taking a leadership role in this noble mission.

“Like the other narratives that guide Putin, this one has deep historical roots, such as those reflected in the story of ‘Moscow as the Third Rome,’” Wertsch said. “In this account, the corruption and decay led the church to move to Constantinople and eventually to Moscow, where Russian Orthodoxy now represents the only pure form of Christianity.”

Challenging the narrative

According to Wertsch, nobody — including allies such as China — will be able to swoop in and change the narrative in Russia. Putin is not listening to anyone but himself. That’s why it is essential to enable different voices to speak up in Russia, he said.

Unlike the Soviet period, when Russians were essentially isolated from the world, today Russians have at least some access to information on the internet and via the Telegram messaging app. Despite the dangers associated with speaking out against Putin, Russians including opposition leader Alexei Navalny are doing just that — trying to find ways to open up democratic discourse and keep it alive.

“Alexei Navalny’s vision of a Russia that includes some sort of parliamentary governance with Russian characteristics might be the best hope for Russia, its neighbors and the world at large,” Wertsch said. “These courageous people need to know that we have not forgotten about them, we support them and we will be there for them in the future when they prevail.”

Wertsch said Biden and his administration have done a “marvelous job” in a very tough situation, so far.

“In the past, we have sent huge amounts of arms into places like Afghanistan, and that came back to bite us. Early on, it was much less clear that Ukraine could put up a real resistance to defeat the Russian army. Biden has balanced this quite well,” he said.

According to Wertsch, NATO is also surpassing expectations — maintaining a real alliance that is more powerful than any one of its members — thanks in part to Biden’s diplomacy and encouragement.

Ultimately, it’s important that Russia is defeated but not humiliated in the process because that can make for a long-standing, bitter animosity, Wertsch said.

“We saw this in Germany after World War I. Germans felt humiliated and abandoned. That humiliation paved the way for Hitler and World War II,” he said. “Overall, I think Biden is doing a great job of getting to Putin by reminding him of his military losses and the support behind Ukraine without humiliating Russia as a whole.”