Understanding how cells die is key to developing new treatments for many diseases, whether the goal is to make cancer cells die or keep healthy cells alive in the face of other illnesses, such as massive infections or strokes. Two new studies from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified a previously unrecognized pathway of cell death — named lysoptosis — and demonstrate how it could lead to new therapies for cervical cancer.

Both studies, which together analyzed data in roundworms, mice and human cells, appear Jan. 12 in the Nature journal Communications Biology.

The blood of patients with cervical cancer and other tumor types is dotted with a protein called SERPINB3. According to the new research, when the gene that manufactures SERPINB3 is absent in cervical cancer cells, the tumor cells die more easily when exposed to the stress of radiation. Similarly, microscopic roundworms called C. elegans that are missing the equivalent gene die more easily when exposed to stresses in their environments.

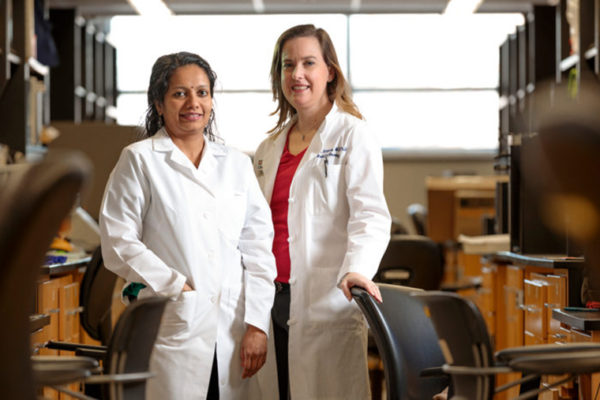

“It’s been known for a long time that high levels of this protein in the blood are a marker of cervical cancer and other squamous cell cancers — the higher the protein levels in the blood, the worse the prognosis,” said Stephanie Markovina, MD, PhD, assistant professor of radiation oncology.

“We wondered if this protein may be doing something to protect the cancer. We thought it was possible that the gene was protecting the cancer cells from stress in the same way the equivalent roundworm gene was protecting C. elegans from stress.”

Markovina collaborated with Gary Silverman, MD, PhD, the Harriet B. Spoehrer Professor and head of the Department of Pediatrics; and Cliff J. Luke, PhD, associate professor of pediatrics, who had been studying this pathway in C. elegans and mice.

“One day I noticed that the worms that had the equivalent gene knocked out were all dying,” Luke said. “I realized that instead of putting the roundworms in the normal saline — or saltwater — that we used, I accidentally put them in regular water. The normal roundworms were totally fine, but the worms lacking the worm-equivalent of the human SERPINB3 gene all died. The plain water was a source of stress, and we determined that they lacked the gene that protects them from stress-induced cell death. We then wondered if this cell death was conserved in mammals. Similar to C. elegans, we showed that intestinal mouse epithelial cells were more sensitive to stress when missing the mouse equivalent of human SERPINB3.”

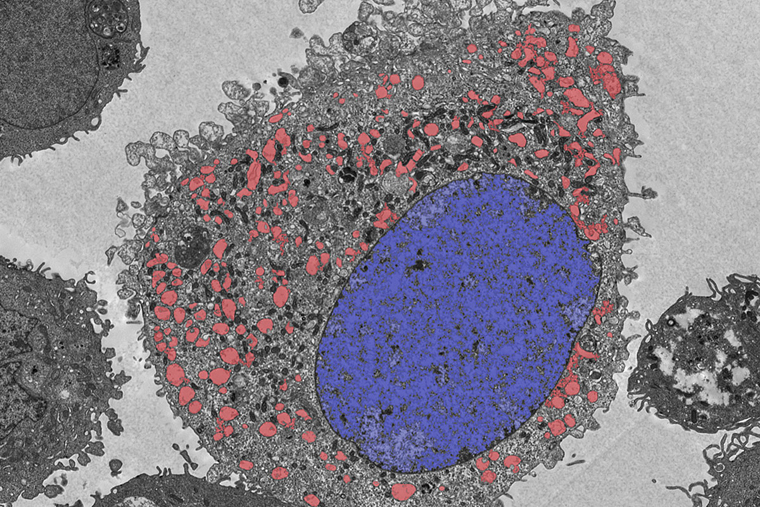

In all cases — roundworms, mice and cervical cancer — the researchers found that this particular mode of cell death is triggered in a specific compartment of the cell known as the lysosome, an important waste-management center responsible for recycling or disposing of cellular waste. The researchers discovered that these genes — called serpin genes — that protect against cell death triggered by the lysosome (lysoptosis) and the cell death pathway itself are conserved across species, from roundworms to humans.

“There are many different cell death pathways, and understanding the specific routes involved in each individual pathway is vital for the treatment of disease,” said Silverman, also a professor of cell biology and physiology, and of genetics, and executive director of the Children’s Discovery Institute at Washington University School of Medicine and St. Louis Children’s Hospital. “The lysosome contains some of the most powerful enzymes in the body. If lysosomes leaked a bit, they could do immeasurable harm to the cell. For this reason, most investigators discounted their role in cell death because their effect would be catastrophic. It was assumed that cells must have multiple protections to prevent this process from ever happening.

“Our work shows that this is not the case,” he said. “Lysosomes leak a bit all the time, and proteins like SERPINB3 are there to neutralize these enzymes if they get out of the lysosome. When SERPINB3 levels are low or absent, or if the stress is strong enough to cause a big lysosomal leak, the cells die quickly, ravaged by the lysosomal enzymes. The cells appear to explode and spew their contents out into the extracellular space, where it triggers an intense inflammatory response. So, lysoptosis signifies an active, stand-alone cell death process that dramatically destroys the cell. This process is very different from apoptosis, in which the cell quietly implodes and the cell debris is cleaned by neighboring cells.”

To study the effects of the SERPINB3 gene, Markovina used the gene editing technology CRISPR to delete the gene from cervical cancer cells. The researchers observed that cervical cancer cells implanted into mice were more susceptible to the stress of chemotherapy and radiation when they were missing this protective gene.

The researchers are screening drugs that are either investigational or already approved by the Food and Drug Administration for other diseases to identify compounds that shut down the SERPINB3 gene in cervical cancer cells, so they can be killed — by lysoptosis — more easily with chemotherapy and radiation.

“As soon as we have a candidate drug, we hope to get it into clinical trials as soon as possible,” said Markovina, who treats patients with gynecological cancers at Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine.

Luke also pointed out situations in which a different treatment that prevents this type of cell death may be beneficial, including in viral or bacterial infections.

“We’re also screening drugs for potential therapies that would enhance the cell protection that this gene confers,” Luke said. “For example, premature infants have a high risk of developing a devastating inflammatory disease called necrotizing enterocolitis, in which the cells of the interior lining of the gut die off. In this case, we would be interested in finding ways to dial up the expression of SERPINB3 to protect against cell death in the gut.”

Added Silverman, “Evidence suggests that lysoptosis is how cells die after massive injury, such as from heart attacks or strokes, or in highly inflammatory conditions like inflammatory bowel disease or necrotizing enterocolitis. In some instances, we would want to manipulate lysoptosis to help kill tumor cells, and in others, we would want to block it when it is inappropriately triggered. We are hopeful this new knowledge can lead to novel therapies for diseases in which this type of cell death plays a key role.”

Luke CJ, Markovina S, et al. Lysoptosis is an evolutionarily conserved cell death pathway moderated by intracellular serpins. Communications Biology. Jan. 12, 2022.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant numbers R01DK104946, R01DK114047, R01DK118568, K08CA237822 and K08AI144033; The Society for Pediatric Research Physician Scientist Award; and American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Career Development Award; and the Children’s Discovery Institute of the St. Louis Children’s Hospital Foundation.

Wang S, Luke CJ, et al. SERPINB3 (SCCA1) inhibits cathepsin L and lysoptosis, protecting cervical cancer cells from chemoradiation. Communications Biology. Jan. 12, 2022.

This work was supported by the Elsa U Pardee Foundation; an American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Career Development Award; an American Society for Therapeutic Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) Junior Faculty Award; and the National Cancer Institute of the NIH, grant numbers K08CA237822 and K12 CA167540; the Washington University Center for Cellular Imaging (WUCCI), supported by Washington University School of Medicine, the Children’s Discovery Institute of Washington University and St. Louis Children’s Hospital, grant numbers CDI-CORE-2015-505 and CDI-CORE-2019-813; and The Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital, grant numbers 3770 and 4642.

Washington University School of Medicine’s 1,700 faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is a leader in medical research, teaching and patient care, and is among the top recipients of research funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.