A city the density of Atlanta or Milwaukee, over a half-million strong, tragically has been wiped from the face of America’s future. Thousands of businesses disappeared, never to return. Millions remained out of work or hardly strayed out of their home, for work or play.

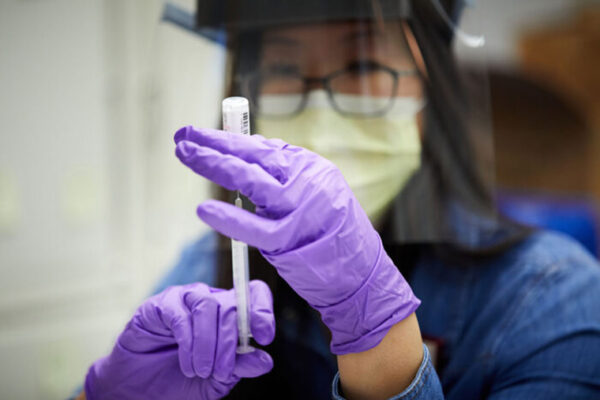

A dose or two of hope, however, arrived near the end of the pandemic’s first year in the form of not one, not two, but three record-breaking vaccines for the dreaded, unseen virus that causes COVID-19.

So where do we go from here, in the second year in these times of coronavirus?

As we mark the one-year anniversary today of the World Health Organization first declaring a global COVID-19 pandemic, Washington University in St. Louis experts, including from its School of Medicine, look both back and ahead.

Of variants and boosters: Will historic shot-making continue?

“Never forgetting the tragic loss of more than a half-million Americans, the past 12 months have witnessed the remarkable discovery, development and distribution of vaccines based largely upon new or unproven technologies. Consider the time needed merely to identify a novel pathogen and begin testing vaccines against it. This span has historically been measured in decades or centuries, with measles holding the recent record, progressing from discovery to testing in just over 10 years. To put this amazing achievement in perspective, the time that elapsed from the identification of SARS-CoV2 until the first vaccine trial occurred in as many weeks.

“Just as remarkable is the fact that the clinical trials for these vaccines were executed with unprecedented efficiency, with three safe and effective vaccines authorized within one year; an achievement that many — including myself — felt impossible months ago. Yet all of this pales in comparison with the final outcome: safe vaccines that block the most dangerous forms of COVID-19. These outcomes have surpassed expectations and reflect an amazing cooperation amongst scientists, physicians, regulators all around the world. From a personal standpoint, I transitioned from merely analyzing clinical trials to volunteering in one. This experience conveyed a new view of our work at the Center for Research Innovation in Biotechnology (CRIB) at Washington University.

“This work is nowhere near completion, though. The rapid and widespread transmission of COVID-19 is creating new variants that will challenge and confound vaccines and treatment. Mutation is a particular specialty of viruses, and SARS-CoV2 is no exception. Given the virus has largely run amok for the past year, these variants could erode the efficiency of vaccines deployed and will likely require updated ‘boosters’ to ensure the hot embers of COVID-19 do not flare into renewed conflagrations.

“Yet, we can rest assured that the amazing scientific and medical momentum achieved over the past 12 months will not abate. Better still, the experiences of the past year may facilitate new and equally exciting opportunities to prevent and treat future microbial pathogens as well as longstanding microbial nemeses and many cancers.”

– Michael Kinch, PhD, associate vice chancellor and director of the Centers for Research Innovation in Biotechnology (CRIB) and Drug Discovery (CDD), School of Medicine.

Race, religion and the vaccine

“The rate of vaccination amongst African American communities is significantly lower than the general public. This is concerning as African Americans comprise a high concentration of frontline jobs, that is employment that requires in-person labor.

“African Americans, for actual historical reasons, have cited distrust of the medical profession as one reason for their hesitancy to be vaccinated.

“However, several cities and states including Tallahassee, Philadelphia and Toledo, Ohio, have experienced significant success educating, testing and vaccinating African Americans within faith communities. This success draws upon the historic and current role Black faith communities specifically and Black activist groups more broadly have played in social-service delivery, especially regarding health and banking. The reality of the social authority of Black clerics also contributes to such success.”

– Lerone Martin, PhD, director of American Culture Studies in Arts & Sciences and associate professor of religion and politics in the Danforth Center on Religion and Politics

Vaccinate, mitigate, remove emotion

“Having millions of doses of three fully tested, safe and effective vaccines within 12 months of a pandemic virus first being identified is mind-boggling. And over the past year, we have learned that human connection is precious and dearly missed when it is taken away; rational decision-making based on scientific evidence is difficult during a pandemic and that we often make decisions based on emotion; and systemic racism is real and can have direct large-scale detrimental effects on health.

“Most challenging in the past year has been watching a mounting death toll in the face of reluctance to consistently message and model the behaviors that would have averted many deaths. A major challenge in the next six months will be navigating how to emerge from the pandemic safely. Some will ditch mitigation measures too quickly and others will cling to them for psychological safety beyond the duration they are needed. How do we factor into the reality that vaccinated individuals have less, but not zero, risk when not everybody has yet had a chance to be vaccinated? How will requiring proof of vaccination further lead to inequities?”

– Steven Lawrence, MD, infectious disease expert, School of Medicine, who studies how to better understand the natural history, impact and mitigation of potentially large-scale infectious disease outbreaks

Curtain pulled back on public health funding, inequities

“The pandemic placed a bright spotlight on public health. It was at the same time gratifying to see higher visibility for public health and recognition of its ability to make a difference in the daily lives of our population … but also troubling to observe our underinvestment in public health.

“The pandemic pulled back the curtain on inequities in society that are in need of immediate attention. We also have seen how the ever-changing information ecosystem affects public health. For example, due in part to a rise in disinformation and heavy use of social media, we now know that false information spreads up to six times more quickly than accurate information.

“There are multiple windows of opportunity to create a brighter future for public health — allowing us to be more prepared for the next public health challenge. First, we need to elect, appoint and cultivate leaders who support evidence-informed policy making. Next, we need to reinvest in public health practice. Without this investment, a new discovery — e.g., the COVID-19 vaccines — will not be deployed effectively and efficiently, with a well-defined and well-funded vaccination campaign. Third, we need to address health and social justice issues across society — we will not achieve population health until we have justice in all sectors, including transportation, education, employment, economics and law enforcement.

“And, finally, we need to identify and teach the critical new skills for the future public health practitioner — issues such as crisis management and communication, policy advocacy and systems thinking.”

– Ross Brownson, PhD, the Steven H. and Susan U. Lipstein Distinguished Professor of Public Health, Brown School

‘We may have to live with (this) forever’

“We’ve learned that it is entirely possible to not only flatten the curve, but end the pandemic through modifying behavior. But you have to have the right mobilization and social and economic fabric to do so — and we did not.

“The fact that this epidemic may not come to a close, with emergent COVID variants circulating, is something we may have to live with forever. The world will have a hard time accepting that.”

– Elvin Geng, MD, epidemiologist and an infectious diseases physician, School of Medicine. During the pandemic, he helped to develop a platform to track information about local transmission that officials needed to make public health decisions.

School closures ‘sideline’ working mothers

“Our research shows schools are a vital source of care for young children, and without full-time, in-person instruction, mothers have been sidelined from the labor force. The longer these conditions remain in place, the more difficult it may be for mothers to fully recover from prolonged spells of non-employment, resulting in reduced occupational opportunities and lifetime earnings.

“Without more support from fathers, employers and the government, something had to give under this unsustainable pressure. What seems to be giving is mothers’ employment.

“This is an injustice with long-term consequences for mothers’ job prospects and economic stability. These are not personal problems, but deeply political issues that require policy interventions. Well-funded and evidence-based reopening plans are necessary to allow children to return to school face-to-face and to allow parents to engage in paid work.

“Now, more than ever, it is crucial that federal and state governments invest in expanding the public care infrastructure for children of all ages.”

– Caitlyn Collins, PhD, assistant professor of sociology in Arts & Sciences and study co-author

How to cope with pandemic anniversary emotions

“People have shared so many different feelings: loss, loneliness, hopelessness, anxiety, depression, boredom, frustration. A lot of us are feeling these things, but for some people they are much more intense, especially for those who have lost access to people or activities that have helped them manage difficult feelings in the past.

“Over the past year, the boundaries between our home lives and our professional lives have changed. During quarantine, we may have attended meetings from our living room or taught class from a bedroom. Email communications have multiplied exponentially because we don’t run into people in the hallways or break rooms like we used to. The expectations for constant work engagement have soared. I think this will be hard to roll back.

“This shared nature of this vulnerability could, in theory, be a source of solidarity and strength. And for some people it has been. Unfortunately, it has also brought out some of the uglier dimensions of our society, as public health measures became deeply politicized and a zero-sum mentality prevailed. Younger generations have watched all of this unfold.”

– Rebecca Lester, PhD, professor of sociocultural anthropology in Arts & Sciences

Read more in a separate story about coping here.

Mental health an ongoing issue; ‘how will we manage it?’

“When I think about COVID one year later, it is amazing to think it has been a year since all of our jobs, lives, work lives, have been upended. I think about how mental health permeates every conversation. When we have uncertainty, we have anxiety. When we have social isolation, we have loneliness and depression. When we have loss, grief, job loss, transition, or are health care workers on the frontlines, it can cause sustained trauma. I think it is important to say that out loud, so we can start processing and coping with it.

“We have learned that connection matters — even the smallest connection. We took for granted how much we liked seeing each other, even in the office, and that even the most introverted among us like to have places where we bump into peers. We like structure, and the change and work/life blend has been hard for all of us. We have had to institute a lot of our own structure on top of all we’re dealing with, to help our mental health.

“Mental health challenges come later — even years later — when people assess the damage and we do not have enough resources to handle the mental health challenges that will stem from the pandemic. We will see long wait lists for care and people who don’t get care. This will be an ongoing issue, and I am not sure how we will manage it.”

– Jessi Gold, MD, psychiatrist, School of Medicine, who focused on treating Washington University health care workers and family members during the pandemic

Doctors ‘push on,’ but hope everyone stays vigilant

“This experience has again reminded me why I chose this profession, why I strive to push when I feel like pulling back and why, despite the toll it has taken on health care providers and more importantly patients and family members, I must push on to keep helping. I think the unrelenting pursuit to be better is what has driven us to get this far.

“The uncertainty and unpredictability of the virus impact has been unprecedented. Often, just when we thought we had an answer it was found to be inadequate. The toll the virus has taken on daily life has been hard to imagine. Something as simple as touching our sick or dying loved ones will hopefully never be taken for granted again.

“As we work to get back to a new sense of normal, it will be important to remember that with the vaccine we must still be smart. Some of the basic safety measures such as masking, social distancing and hand washing must still be a part of our daily routine. As we begin to socialize and find an escape from the physical and mental stress that we have all endured over the past year, we must be vigilant in doing it safely.”

– Praveen Chenna, MD, pulmonologist, School of Medicine, who spent the past year caring for critically ill COVID patients in the ICU

‘I have personally witnessed strength, compassion, humanity….’

“When the pandemic began, we did not know what we were dealing with — except that it was dangerous and deadly. Although there were good reasons to be concerned or afraid, our physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, technicians, custodial service providers, unit secretaries, transport, admin and so many more stood shoulder to shoulder, working together to meet the needs of our community. Many suffered our own losses and milestone events within our families, yet we came to work and did our jobs with pride and compassion. I have personally witnessed the strength, compassion, humanity and, yes, beauty, in the care delivered at the bedside.

“This year has been challenging. I know we are tired for many reasons. However, we provided care and comfort to people at their most vulnerable times and made a difference in the lives of others. I am proud to walk among people who bring such value and humanity into the world.”

– Tiffany M. Osborn, MD, is a critical care and emergency medicine specialist, School of Medicine, who has provided care to patients with COVID-19 over the past year

Courage, collaboration on the frontline

“The most challenging thing I faced in the past year was the fear early in the pandemic that, by doing the job I love, I could inadvertently be exposing my family to harm.

“I already liked my colleagues, but I love them after braving this pandemic together. We all stepped out of our comfort zone to take excellent care of patients in the face of great uncertainty and potential personal harm. We had a telemedicine system up and running in two weeks. We covered for each other without complaint through daycare closures and quarantines.

“We also felt support from others in our community — the Lowenhaupt family gave us a generous gift allowing us to give patients free blood pressure cuffs to support remote monitoring and telemedicine prenatal visits. The pandemic has shown me the very best of humanity.”

– Ebony Boyce Carter, MD, is an obstetrician-gynecologist, School of Medicine, who has delivered babies throughout the pandemic and whose research involves community-based interventions to promote health equity for pregnant women and their babies

Helping Americans a 2-1-1 call away

“We’ve been tracking the day-to-day needs of Americans in 38 states since the COVID-19 pandemic began — examining over 14 million requests for help. Although needs related to food, jobs and utility payments are much higher than pre-COVID-19, what really stands out is how many people are struggling with housing. Requests for rent assistance have increased every month since May and are 2-3 higher than before the pandemic. Landlord-tenant issues are also sharply higher and still rising, over twice their normal rate. The pandemic has turned a lot of serious social challenges into full-blown crises, and affordable housing is at the top of that list.”

– Matthew Kreuter, PhD, the Kahn Family Professor of Public Health and senior scientist, who oversees the study of the national 2-1-1 helpline in the Health Communication Research Laboratory in the Brown School

Older adults as essential workers

“There is no doubt: Older adults are disproportionately affected by this pandemic. They are more likely to get sicker, to be hospitalized, to need the ICU and to die from COVID-19 than younger people. Immunosenescence and an increased number of underlying conditions put older bodies at higher risk for morbidity and mortality. These are the facts, and they have been interpreted from the traditional ‘age drain perspective’ — older adults as burden, as problem, as vulnerable and as dispensable.

“These are hard realities about older adults during the pandemic, and there are other realities that need to be communicated. There is this other side of the pandemic story:

• The older population is very heterogeneous, including people from 65 to 110+ years of age, with all levels of physical health, cognitive health, social connection and economic resources. Chronological age is not the best descriptor of an older individual.

• Older people are well represented among essential workers: They are part of the workforce and the volunteer labor force, and they have important roles as caregivers and grandparents.

• The older population is a critical part of the economy as producers and consumers. We cannot pick older adults or the economy; they are closely intertwined.

• Nursing home residents have been hit the hardest by COVID-19, but, remember, less than 5% of people over the age of 65 live in residential settings, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

• Compared to younger generations, older people report coping fairly well during the pandemic. According to a recent national survey by Edward Jones and Age Wave, 21% of Generation Z reported coping “very well” during the pandemic, compared to 33% of Boomers and 39% of the Silent Generation.

• Data from the Social Policy Institute at WashU suggest that, compared to younger generations, older people are better at practicing health protective behaviors, such as mask wearing, distancing and hand washing. In other words, they behave more vigilantly about protecting themselves and others.

“We believe that this more complete and accurate narrative will lead to policies and practices that eliminate barriers for older people to fully participate in society — before, during and after the pandemic.”

– Nancy Morrow Howell, PhD, the Bettie Bofinger Brown Distinguished Professor of Social Policy in the Brown School

The pressure of every experiment

“In the past year, we have learned a tremendous amount about how a completely new virus causes severe disease. This has allowed us to manage it better clinically and design novel therapeutic strategies and drugs that are improving outcomes. We also learned how to make and deploy vaccines in a record time — this has been nothing short of amazing.

“What’s been most challenging is the social isolation from family and friends. Working everyday knowing that every experiment matters and can have an impact — this is both a blessing and a burden. Worrying about others getting sick and dying, including members of your extended family. Losing people to a disease that, if we had more time, we could control.”

– Michael Diamond, MD, PhD, virologist, who worked with David Curiel, MD, PhD, School of Medicine, to develop a nasal vaccine for COVID-19 that is in Phase I clinical trial in India. In addition, Diamond recently published research suggesting that COVID-19 antibodies and vaccines may be less effective against worrisome, rapidly spreading variants.

‘We’ll need a national strategy’ for future

“We’ve learned that infectious diseases — particularly emerging infectious and drug-resistant microbes — pose a serious threat to our society for which we need to be better prepared. Looking ahead, we’ll need to develop a national strategy to coordinate research and plan how to respond to future pandemics.

“It’s been challenging to see the undermining of experts in science and public health as well as the politicization of science and the public health measures [such as wearing masks and social distancing] to combat the pandemic.”

– Sean Whelan, PhD, head of molecular microbiology, School of Medicine, transformed an unused room in his lab into a biosafety level 3 (BSL-3) laboratory in a matter of weeks so that he could study the SARS-CoV-2 virus. As part of his research, he developed a hybrid virus that infects cells and is recognized by antibodies but lacks the ability to cause severe disease. The hybrid virus made it possible for researchers across the world to study COVID-19 under normal laboratory conditions.

Continuing to learn to combat aerosols

“Early observations during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic suggested that aerosol transmission played a significant role in spreading the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Not all viruses can transmit efficiently through this airborne route, and it was clear that immediate communication would be required between aerosol experts, health care professionals and the public. Here at WashU, many collaborative teams across disciplines sprinted to answer critical questions and produce improvised solutions to prevent COVID-19 transmission.

“We have learned a lot this past year about the capabilities of various materials and mask designs. A good mask should filter particles of different sizes, fit well on the face without leaks, and allow for low-resistance breathability. Companies have developed this technology over many years to produce highly effective respirators – such as those rated as N95 – and surgical masks, which are both used by healthcare workers. When those materials and manufacturing capacity have been in short supply during the pandemic, it has been a challenge to produce improvised substitutes that meet the same requirements.

“While we may plan ahead and be better equipped with personal protective equipment for future outbreaks, we should also work to improve the infrastructure of our indoor environments to provide better air filtration and ventilation in public spaces. There have been too few studies on the air quality of indoor spaces, and given the amount of time we spend indoors (more than 90% in the U.S.), along with the wide range of indoor spaces, we need to improve our understanding of exposures to viruses and many other toxic chemicals and particles in these environments. Some simple methods can be used to quickly advance our basic understanding of air ventilation variability throughout buildings. For example, low-cost carbon dioxide meters can be installed in public spaces to track the ventilation rate of the immediate space, providing a metric that can be used to set health-based thresholds for occupancy or identify a need for enhanced ventilation.”

– Brent Williams, associate professor in energy, environmental and chemical engineering

Innovating=problem-solving

“At WashU Olin, when it comes to entrepreneurship, we first teach students to ‘fall in love with the problem.’ If an entrepreneur can understand the root of a customer’s problem, then there is clarity and understanding of the right ‘solution’ to build.

“During the pandemic, problems were suddenly appearing everywhere. And the race to innovate and solve those problems was the most rapid I’ve seen since the initial dot.com craze in the late ’90s. Solving acute, short-term problems feels good … but it is not a long-term strategy, and it certainly doesn’t lead to eventual sustainability for your organization. The opportunity now is to call a timeout and reassess all you’ve been doing recently to decide which of your new solutions are simply acute versus ones that can set your customers and you up for long-term success.

“We will not be in a pandemic forever. But the world will not be exactly the same afterwards, either. It’s hard to hear and we’re all tired, but it is time right now to innovate yet again.”

– Doug Villhard, professor of practice in entrepreneurship and academic director for entrepreneurship, Olin Business School

Demand to pain consumers awhile

“We feared supply-chain shocks would feel some temporary pandemic pain, but strong customer demand coming back killed us. The ‘bullwhip’ is still the king of the supply chains, and its pain is deeper and longer lasting.

“As the virus emerged in Wuhan, China, durable goods manufacturers from cars, appliances, TV sets, audio equipment, furniture and boats braced themselves for supply shocks as the ‘factory of the world’ was disrupted.

“As the summer came, and most of us got used to a life with limited or no access to dining services, sports venues and other entertainment, we fell in love with our own houses, kitchens, in-home entertainment devices, exercise equipment, power tools, furniture, cars and boats. The demand for those products came back at a speed of recovery and level nobody expected. By persisting for six months or so, such conditions unleashed a ‘bullwhip’ that pained these supply chains as never before. The ripple effect wasn’t a 10-20% increase down the line to manufacturers and raw-material suppliers, but rather reached 50-100% levels. Shortages followed — exacerbated by shortages in semiconductors and one essential of supply-chain transportation, shipping containers.

“In an anticipated future mismatch of supply and demand, and projected higher future prices, we are investing now to capture the projected peak. So we are all gaming the system in trying to hoard the limited-capacity resources accentuating the severity of current bottlenecks in the supply chain. But in the current, (ab)normal state of the world, with highly changed consumer behaviors, the demand peaks are higher and longer persisting, and our forecasts even more erratic. The logistics bottlenecks in ports, ocean and air cargo are still limiting global flows and severely elongating lead-times — so how long have you been waiting for your exercise bike?

“In a connected world overloaded with ‘dirty data’ and misinformation, profit-maximizing corporate entities are afraid of shortages of crucial resources, thus they inflate forecasts, lie about lead-times and have unexpected cancellations — all part of a game perfected and magnified in its consequences. For all these reasons, the ‘bullwhip’ is cracking louder; the shortages will be longer persisting, and we will feel deeper the economic pain of revenue losses and increases in supply costs. As consumers, we will have to wait longer and pay higher prices to get our dream durable goods.”

– Panos Kouvelis, PhD, director of The Boeing Center for Supply Chain Innovation and Emerson Distinguished Professor of Operations and Manufacturing Management, Olin Business School

Emergency vaccine supply chain must become long-term strategy

“An unforgettable 2020 witnessed a record-fast vaccine development. Across industries, extraordinary vaccine manufacturing and deployment efforts have been exerted to meet the urgent need to inoculate the world’s population against COVID-19, involving production alliance between pharmaceutical rivals and retailers enlisted in distribution.

“While countries around the world are still on their learning curves of rolling out the first vaccines, new coronavirus variants continue to emerge. What has been pulled off as an emergency response needs to be developed into a sustainable, systematic, long-term strategy to fight against the virus, which is likely to persist for the foreseeable future.

“A vital part of this long-term strategy is to build reliable and responsive vaccine supply chains: 1) Each stage is adequately equipped to ensure safe and fast vaccine distribution. 2) The end-to-end supply chain visibility provides valuable data to inform vaccine R&D, manufacturing and distribution planning. 3) It also can facilitate the timely, cross-region, supply-demand rebalance and efficient planning of local events where vaccines are administered. And 4) that end-to-end visibility directs proper intervention in underserved regions.”

– Lingxiu Dong, PhD, professor of operations and manufacturing management, Olin Business School

Ending mask mandates could hurt economy

Several states easing mask restrictions in March not only goes against the advice of federal health officials, it also contradicts the findings of Olin Business School researchers who found mask mandates boost the economy.

“Our research shows that mask mandates help increase consumer spending. The issue with the economy has always been that customers are hesitant to go out and shop, and having a mask mandate tends to increase consumer spending by about 4%. Thus, cutting the mask mandate is certainly unlikely to help the economy.

“That said, the effect of opening restaurants and removing mask mandates on the spread of COVID is probably going to be smaller than it would have been a couple of months ago since COVID cases in general are much lower than they were in the winter, and with nicer weather coming in people can naturally distance better than they were before. Compliance with mask mandates has also been uneven, so the impact is likely more about how the laws change people’s mindsets than about the direct effect of the mandate.

“While COVID-19 cases are trending down, and people are rapidly getting vaccinated, having people interact more directly, inside and without masks does give the COVID-19 virus more of an opportunity to evolve to another form that might be resistant to the current vaccines. If such a variant comes into being, that will have huge costs on both people’s health and the economy.

“In this sense, waiting two to three months for most of the population to be vaccinated might have a lot of long-term benefits with only limited short-term costs.”

– Raphael Thomadsen, PhD, professor of marketing and study co-author, Olin Business School

Working from home is here to stay

“Some surveys show a sizeable majority of organizations plan to give workers the option of working from home between one to four days per week. So, although most companies aren’t planning to remain fully virtual, they are planning to adopt a hybrid mode of working to retain some of the flexibility of a work-from-home model.”

A recent Pew Research Center study found nearly 90% of people who have been working from home during the pandemic do not want to return to the office full-time.

“Companies are also making this decision because it will save money on real estate and facilities. In a recent KPMG survey, more than two-thirds of CEOs reported that they are planning to downsize office space. In my view, this is the strongest indicator that some form of work-from-home will stay — CEOs are putting their money where their mouths are.”

– Andrew Knight, PhD, professor of organizational behavior, Olin Business School

WFH2.0: spontaneity, flexibility

“Amongst many things, this past year generated a massive experiment in what it meant to run our businesses/non-profits/schools with the talent working from home (WFH). So, what did we learn?

“On the one hand, turning any spare bedroom into a home office has made us nimble in disconnecting the ability to get things done from any particular physical site. It turns out that pulling back on co-worker distractions and adding an ability to take breaks when the mind requires rest has helped many of us settle into a new productivity groove. On the other hand, dislocation from co-workers has made generating innovative, out-of-the-box initiatives much more difficult.

“While I am hopeful this year has helped leaders realize that many can be quite productive with a greater level of autonomy, individuals and organizations need a new set of skills and processes to generate ideas in a world where collaboration has become overly structured into hour-long Zoom calls and spontaneity correspondingly squeezed. With companies running the gamut from saying you can WFH forever to others suggesting this past year was a blip on the radar, I hope more organizations find a way to strike a balance between autonomy and coordination.

“Work might be a better place if employees are given freedom to get their job done. At the same time, if this flexibility doesn’t come alongside novel methods of collaboration, the future of work might come at the cost of a specific kind of innovation that requires spontaneity and flexible forms of coordination!”

– Peter Boumgarden, PhD, director of the Koch Family Center for Family Enterprise and academic director of the Center for Experiential Learning, Olin Business School

Contributing to this story were: Caroline Arbanas, Judy Martin Finch, Chuck Finder, Sara Savat, Neil Schoenherr and Diane Duke Williams.