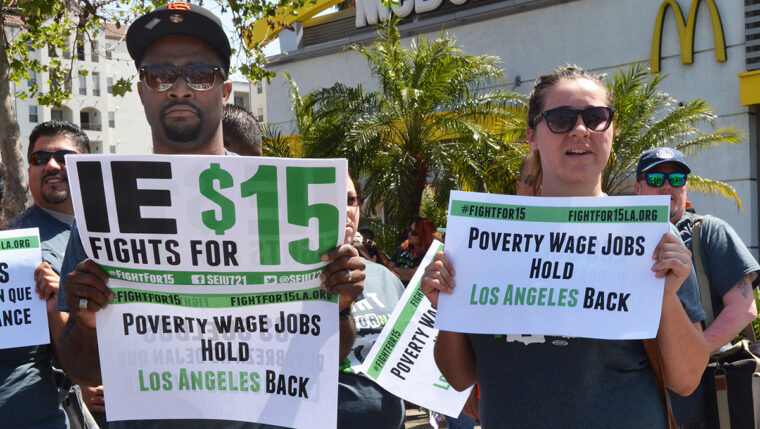

If the post-pandemic economic return includes minimum-wage increases across a few or many states, research led by Washington University in St. Louis scientists in the Olin Business School suggests that some positive and negative effects for U.S. workers follow in the two years after implementation.

On the positive side, their study shows that minimum-wage hikes not only increase the wages of those workers but also create a positive “spillover” effect on the wages of other workers earning up to $2.50 above the minimum wage. Not only do these workers experience a wage increase, but they also continue to retain their jobs as they are no more likely to be fired.

On the negative side, the study highlights that a higher minimum wage is bad news for new entrants into the labor market. The researchers find that businesses, especially those making tradeable goods — such as the manufacturing sector — reduce the rate of hiring new workers at low wages.

The study is forthcoming in the Journal of Labor Economics.

“In general, minimum-wage increases following a crisis is not a good idea as it is likely to make a bad situation worse,” said co-author Radhakrishnan Gopalan, professor of finance in the Olin Business School. “We will have a tremendous number of individuals looking for jobs post-crisis, and our study indicates that a higher minimum wage is especially detrimental for this particular sub-population — folks looking for new low-wage employment.

“Given the important role of the minimum wage in ensuring that households have a living wage, it is essential to study its impact on workers and businesses. Furthermore, many have pointed to the minimum wage not keeping up with inflation as contributing to the worsening wage inequality and overall economic inequality in the U.S.”

Added co-author Barton Hamilton, the Robert Brookings Smith Distinguished Professor of Economics, Management and Entrepreneurship: “Our findings suggest that the impact of a higher minimum wage on income inequality depends on who you are. If you have a job that pays at or near the minimum, you are better off. If you do not have a job, such as many young workers just entering the labor force, employers will be less willing to hire you. So inequality might be reduced for older, more experienced workers, but may increase for younger, inexperienced workers.”

Gopalan, Hamilton — who also serves as the inaugural director of the Koch Center for Family Business — and two Olin PhD graduates, Ankit Kalda of Indiana University and David Sovich of the University of Kentucky, used Equifax data to study six states that enacted minimum-wage increases between 75 cents and $1.25 per hour in the 2010-15 period and compared employees in border counties of neighboring states that didn’t have a minimum-wage increase. Overall, the 2010-15 study period covered 22.5 million active employee records in their sample.

The median personal income of the study group for 2015 stood at $34,970, about $4,000 higher than the U.S. median that year, $30,622. However, the median tenure of employees in their sample was 3.5 years, roughly three-fourths of a year less than the U.S. median of 4.2 years.

The six studied states with a higher minimum wage were: California, Nebraska, South Dakota, Michigan, West Virginia and Massachusetts. The co-authors also scrutinized data for bordering counties in Nevada, Wyoming, North Dakota, Iowa, Kansas, Wisconsin, Indiana, Kentucky, Pennsylvania, Virginia and New Hampshire.

The paper did not find much evidence for labor reallocation, where businesses in states without minimum-wage hikes hire increased numbers of low-wage workers, compensating for hiring decreases in states with such hikes. Rather, what happened was merely a slower rate of hiring following voluntary turnover — say, three leave and two new workers are hired. The co-authors indeed found high rates of turnover: On average, 54% of workers below a state’s new minimum wage separated within 12 months of hiring.

Pandemic or no, pay inequity or imbalance has been considered an issue from the manufacturing floor to the C-suite. Mining the payroll data, the co-authors wrote that they discovered, on average, low-wage employees comprise 52% of “establishment employment and 29% of payroll.”

“Our paper would predict a slower new-hire rate in places where the wage rates were lower to start.”

Radhakrishnan Gopalan

Because of the economic crisis resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, some cities and states have contemplated or, in the case of Virginia, publicly announced they want to rescind or postpone minimum-wage hikes scheduled to go into effect in 2020. Additional states with scheduled, upcoming increases on their books include: Arkansas, California (again), Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts (again), Michigan, Missouri, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York and Oregon.

The $600 weekly unemployment benefit under the CARES Act “is a pseudo wage increase” through the Act’s end, Gopalan said. “This is because any business wanting to hire workers should match their unemployment benefit. Our paper would predict a slower new-hire rate in places where the wage rates were lower to start. The effect especially could be adverse in areas where employment is dominated by firms making tradeable goods, such as in the manufacturing sector.”

WashU Response to COVID-19

Visit coronavirus.wustl.edu for the latest information about WashU updates and policies. See all stories related to COVID-19.