Restricting the sale of menthol cigarettes to tobacco specialty shops may reduce the number of retailers and increase the cost of smoking, according to new research from the Brown School at Washington University in St. Louis.

“Targeting the tobacco retail environment is rapidly emerging as the next frontier in tobacco control,” said Todd Combs, research assistant professor at the Brown School and lead author of the study “Modelling the Impact of Menthol Sales Restrictions and Retailer Density Reduction Policies: Insights From Tobacco Town Minnesota,” published Aug. 28 in the journal Tobacco Control.

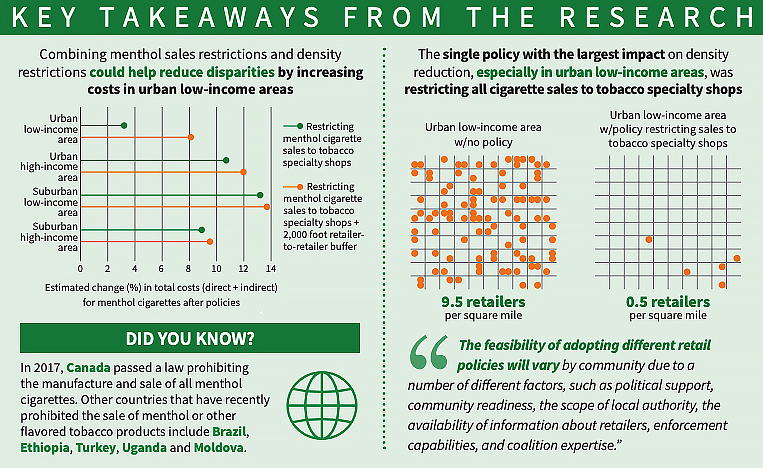

“Policies focused on the places tobacco is sold can reduce tobacco use and tobacco-related health disparities by increasing the direct and indirect costs of tobacco to consumers,” Combs said.

Researchers used a computer model called Tobacco Town to test the effect of five retail restrictions on the reduction of retailer density; total cost per cigarette pack; and the average distance customers travel to buy cigarettes.

The model was based on data from six communities in Minnesota that are planning or have enacted menthol restrictions. During each simulated day in the model, computer-generated “people” smoke and make decisions on when and where to buy cigarettes.

Of those tested, the single policy with the largest impact on density reduction, especially in urban low-income areas, was restricting all cigarette sales to tobacco specialty shops. Restricting all cigarette sales or menthol cigarette sales in that way also may have the largest effect on the total direct and indirect costs of cigarettes.

In almost all of the simulations, low-income population and African Americans were the groups least impacted by policy changes, likely because they live in retailer-dense areas. That finding led the authors to suggest combining density restrictions and sales restrictions to reduce disparities.

“Communities often implement policies to reduce health disparities among priority populations,” Combs said. “Our results suggest that retail policies aimed at increasing direct and indirect costs of purchasing cigarettes and, presumably, reducing smoking among low-income or black or African-American populations might impact them less than for the overall population. This is likely because they live in retailer-dense areas (black or African-American smokers) or travel farther on average (lower income smokers) to purchase cheaper products.”