One of the most common causes of diarrhea worldwide – accounting for millions of cases and tens of thousands of deaths, mostly of small children – is the parasite Cryptosporidium. Doctors can treat children with Cryptosporidium for dehydration, but unlike many other causes of diarrhea, there are no drugs to kill the parasite or vaccines to prevent infection.

Now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have figured out how to grow the most common type of Cryptosporidium in the lab, a technological advance that will accelerate efforts to treat the deadly infection.

“This parasite was described over 100 years ago, and scientists have never been able to reliably grow it in the lab, which has hampered our ability to understand the parasite and develop treatments for it,” said senior author L. David Sibley, the Alan A. and Edith L. Wolff Distinguished Professor of Molecular Microbiology. “We now have a way to cultivate it, propagate it, modify its genes and start figuring out how it causes disease in children. This is a first step toward screening potential drugs and finding new drugs or vaccine targets.”

The findings are published online June 20 in Cell Host & Microbe.

In wealthy countries, Cryptosporidium is notorious for causing water-borne outbreaks of diarrhea. The parasite goes through a complex life cycle, including a stage in which it is called an oocyst and becomes hardy, spore-like and hard to kill with chlorine, bleach or other routine sanitation measures. In 1993, 400,000 people in the Milwaukee area developed diarrhea, stomach cramps and fever after a malfunctioning water purification plant allowed Cryptosporidium into the city’s water supply. Every year, dozens of smaller outbreaks are reported in the U.S., many associated with swimming pools and water playgrounds.

Diarrhea caused by the parasite can last for weeks. While this is miserable for otherwise healthy people, it can be life-threatening for undernourished children and people with compromised immune systems.

Until now, researchers who wanted to study the parasite had to obtain oocysts from infected calves – Cryptosporidium infection is a serious problem in commercial cattle farming – and grow the parasites in human or mouse cell lines. The parasite inevitably would die after a few days without going through a complete life cycle, so the researchers would have to obtain more oocysts from cattle to do more experiments.

Sibley, along with co-first authors Georgia Wilke, who is a student in the Medical Scientist Training Program, and postdoctoral researcher Lisa Funkhouser-Jones, suspected that the problem lay in the cell lines traditionally used to grow the parasite. Derived from cancer cells, these cell lines were very different from the normal, healthy intestine that is the parasites’ usual home.

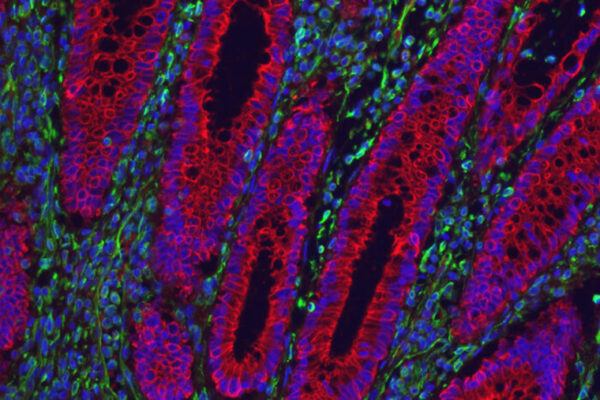

To create a more natural environment, the researchers collaborated with Thaddeus S. Stappenbeck, MD, PhD, the Conan Professor of Laboratory and Genomic Medicine and a co-author on the paper. Stappenbeck and colleagues cultured intestinal stem cells to become “mini-guts” in a dish – complete with all the cell types and structural complexity of a real intestine.

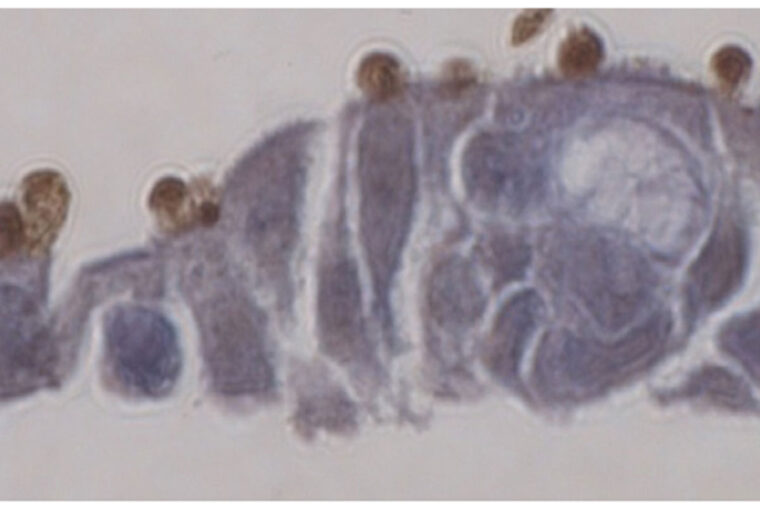

When the researchers added oocysts to the mini-guts, the parasites thrived. They emerged from the oocysts and went through their full life cycle to produce more oocysts. For the first time, every stage of the parasite’s complicated life cycle could be studied in the lab. The researchers also showed that they could edit the parasite’s genes with CRISPR/Cas9 and perform genetic crosses, making these powerful tools for studying biology more accessible than before.

“We put the parasite in this environment that is much more natural, and it’s happy and it grows and develops and goes through the entire life cycle,” Sibley said. “This opens up possibilities that were closed for a long time. There is only one FDA-approved drug, and it doesn’t work in young children. There are potential drug candidates, but we couldn’t screen them before because the parasites would just die anyway. How can you tell if the drug is killing the parasites if they are already dying? Now we can start screening drugs and also start asking questions about what makes this parasite dangerous.”

The technique applies only to C. parvum, one of the two most common Cryptosporidium species that cause diarrhea in people. Its cousin C. hominis is even more difficult to grow in the lab. The two are closely related, but while C. parvum can infect young mammals of many species, C. hominis only infects people.

“There are only a few dozen genes that are different between parvum and hominis but somehow that’s enough to make hominis very finicky,” Sibley said. “It won’t grow in mice or in calves or, so far, in mini-guts grown from mouse stem cells. Developing systems to work with hominis is an important goal of my lab.”

The technique, while potentially powerful, will not immediately translate into better treatment or prevention for diarrhea, Sibley cautioned.

“These things take time,” Sibley said. “There’s a lot of basic research that still needs to be done. But this system provides an important path forward. We can now use genetic approaches to study the role of individual genes and thereby identify important targets for improved therapies.”