Researchers at Washington University in St. Louis have a unique resource in the form of the Center for Biomolecular Condensates at the McKelvey School of Engineering, which draws scientists from around the world to study the biochemical reactions of condensates, constantly shifting, membrane-less organelles that govern how a cell functions.

Center Director Rohit Pappu, the Gene K. Beare Distinguished Professor, has spent his career defining and outlining the rules governing these “intrinsically disordered proteins” to develop medical treatments for cancers or dementias. But new medicine is not the only treasure to uncover in condensate research.

His colleague at the center, Yifan Dai, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering, is making a mark for taking what they’ve learned from condensates and applying the tools to “directed evolution.” The idea is to create new biological levers and processes, a toolkit for bioproduction that can benefit humanity in all sorts of arenas.

In a paper published recently in Nature Materials, Dai’s team demonstrates how these constantly shifting clumps of protein material can generate electricity, delivering a new framework for engineering biomaterials that could power bioelectrochemical devices. Such devices could be used in a range of ways, from fighting infection to cleaning up pollutants.

In the new research, Dai outlines how condensates can act as “battery droplets.” Inside a battery, the real action happens at the interface — the thin boundary where the electrode and electrolytes touch. An “interfacial” electric field drives chemical reactions within a cell in a similar manner, converting chemical energy to electrical energy.

Protein condensates are formed through the phase transition of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs). This process is governed by the interplay between the solvent (water and ions) and physical properties of these cell materials. Such material naturally creates a setting conducive to creating a nanoscale electrochemical battery.

Although they lack the metal plate electrode used in batteries, the proteins still have an interface that serves the same purpose: a surface where a condensate meets the surrounding solvent, where certain ions and molecules prefer one side over the other. That uneven distribution creates tiny electrical imbalances, like miniature voltages inside the cell.

This voltage can drive electrochemical reactions like the metal electrode, thereby powering electron transfer. And because these droplets move, bump into membranes, and fuse with each other, their interfaces are constantly rearranging — charging and discharging in bursts.

In other words, cells may be filled with countless of these soft “battery droplets” that store and release electrochemical energy on demand, giving synthetic biologists a dynamic new way to power signals and reactions, Dai said.

In this research, the team demonstrates how genetically encoded protein materials that can undergo self-assembling into protein condensates can be engineered as an “electrogenic protein powerhouse.” That powerhouse can be programmable depending on how they tinker with those surface residues and the extent of charge imbalance of the phase transition.

With a powerful battery droplet that can operate in living cells, the potential applications for this biotechnology are boundless.

Dai’s team demonstrated that microscale “engines” can drive a bit of alchemy, producing gold and copper nanoparticles directly in living cells. Such “biohybrid” devices could be used to degrade pollution in wastewater. Further, through the same protein materials, they show how the redox reactions can be exploited to kill bacteria without using antibiotics, which could lead to many new medical devices to improve human health.

Evolution takes the wheel

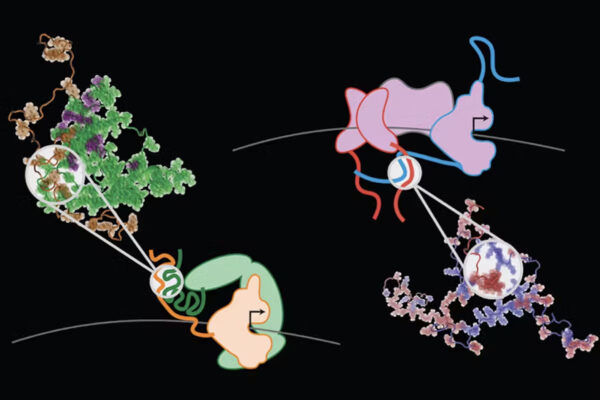

On the antibiotic front, Dai’s team published further research this month in Nature Chemical Biology, demonstrating their “directed evolution-based” method for evolving synthetic condensates and soluble disordered proteins that could eventually reverse antibiotic resistance and help regulate protein activity among cells.

“Directed evolution,” Dai explained, is letting the rules of how condensates evolved guide their synthetic biology endeavors.

Directed evolution has been used as a way to evolve structured proteins. This work was recognized with the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2018. However, its potential in evolving non-structured, or disordered, proteins has not been exploited due to the lack of connection between cellular fitness and evolution, Dai explained.

“We designed the evolution-based assay and selection strategies to connect cellular survival and the behaviors of the disordered proteins, then put them into different temperatures or other selective pressures, and let it go,” Dai said. “We let nature do the work to give us a sequence that can behave and let them survive.”

Dai’s lab, including first authors and graduate students Yuefeng Ma, Leshan Yang and others, used E. coli bacteria for its experiments because it grows quickly, is easy to work with and allows for efficient screening of many protein variations. E. coli is also simpler than mammalian cells, which have more complex systems that could interfere with the evolution process.

“Overall, this evolution-based method could be useful not just in synthetic biology, but also in studying protein behavior in biochemistry and cell biology, helping to understand how protein sequences influence their functions,” Ma said.

Future work will focus on developing context-dependent evolution strategy in mammalian cells, which could help refine a new platform to create condensate-dependent therapeutics, Ma added.

Dai and Ma are co-inventors on a U.S. provisional patent application. They are working with WashU’s Office of Technology Management, which is assisting in protecting the intellectual property and advancing commercialization efforts.

Ma Y, Yang L, Chen Y, Chen MW, Yu W, Dai Y. Directed evolution of functional intrinsically disordered proteins. Nature Chemical Biology, Jan. 9, 2026, DOI: 10.1038/s41589-025-02128-3

Yu W, Ma Y, YangL, Zhou Y, Liu X, Dai Y. Electrogenic protein condensates as intracellular electrochemical reactors. Nat Mater. 2026 Jan. 15 DOI: 10.1038/s41563-025-02434-0