Celebrated editor, publisher and art collector Larry Warsh recently gifted 56 works of Chinese photography to the Kemper Art Museum at Washington University in St. Louis.

This spring, the museum will publicly display 43 of those works, all made between 1993 and 2006, for the first time. “Looking Back Toward the Future: Contemporary Photography from China,” on view Feb. 27 to July 27, will explore how a generation of avant-garde Chinese artists used large-scale photography and ephemeral performance art to visualize changing urban and social landscapes, capturing and criticizing Westernization and the disappearance of genuine Chinese history and culture. The photographs employ a diverse range of photographic methods unique to this moment in Chinese history.

“This gift constitutes a major expansion of the Kemper Art Museum’s holdings of contemporary Chinese art,” said Sabine Eckmann, the William T. Kemper Director and chief curator at the Kemper Art Museum. “It substantially expands the representation of global voices within the museum’s permanent collection and contributes to Washington University’s study of Asian art and culture. We are extremely grateful to Larry for this generous gift.”

Warsh began collecting Chinese photography more than two decades ago, during a trip to Beijing. “These artists were grappling with some of the most critical issues of their time, and yet their work remains little seen, both in China and in the West. It is important for me to help shine a light on this critical transitional moment in the history of Chinese art.”

The gift complements the Kemper Art Museum’s 2022 acquisition of world-renowned artist Ai Weiwei’s “Illumination” (2019), which was made possible by the William T. Kemper Foundation to further the musem’s goal to curate a more globally distinct collection. Though Ai is not featured in “Looking Back Toward the Future,” several of the 14 artists — including Rong Rong, Zhang Huan and Cang Xin — were associated with the East Village Beijing. The short-lived creative enclave took inspiration and its ironic nickname from Ai’s time living in Manhattan, N.Y.’s East Village, then a notable center for contemporary art.

Eckmann, who curated “Looking Back Toward the Future,” noted that, in the years following the Tiananmen Square democracy protests, the violent suppression by government forces and the forced closure of the Beijing National Gallery’s “Avant-Garde” exhibition — all of which took place in 1989 — much of this work was considered provocative.

“Arrests were frequent,” Eckmann said. “A 1994 police raid completely dismantled the East Village, and many artists were forced to go underground or flee the country. The work still has not received the attention it deserves. Especially considering the Chinese and Chinese-American population at WashU and in the St. Louis community, the Kemper Art Museum is honored to showcase these historically significant works.”

The exhibition is divided into three interrelated thematic sections: “The Presence of the Past,” “East and West” and “Performance and the Body.” Together, they explore how, for the first time in the history of Chinese photography, avant-garde artists engaged with the medium’s conceptual and expressive potentials to chronicle, critique and reflect on China’s global transformation and its increasingly powerful market economy.

‘The Presence of the Past’

“The Presence of the Past,” which opens the exhibition, visualizes artists’ often ambiguous efforts to evoke and memorialize China’s distinctive cultural heritage amid rapid erasures of the nation’s histories and the rise of a globalized, ultramodern built environment. They also turned to the camera as a tool to record changes in the lived experiences of individuals and families.

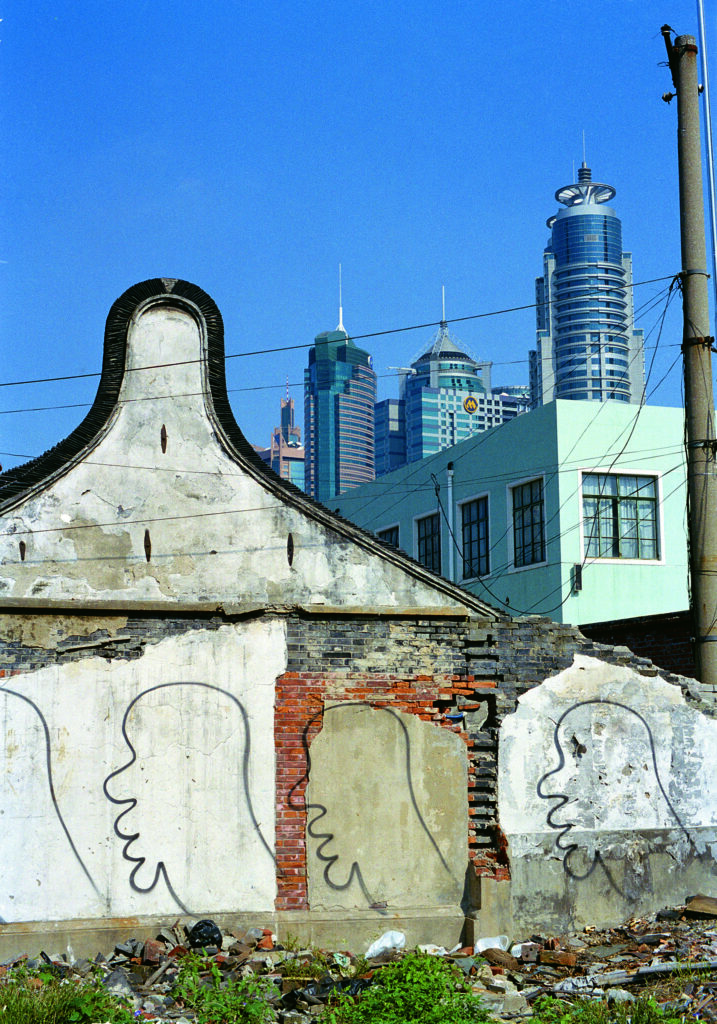

Zhang Dali’s photographs of Beijing juxtapose demolition sites, which he marked with graffiti, against contemporary and traditional towers. Wang Jinsong’s “Standard Family” (1996) examines the generational echoes of population control while his “100 Signs of Demolition” series (1999) collects spray-painted examples of the Chinese character 拆 (chāi, or “demolish”), used to mark buildings for destruction.

Weng Fen’s “Girls in Hoods No. 4” (2004) pays homage to his native Hainan, a rapidly urbanizing island province, through a haunting figure framed by dramatic expanses of ocean and sky. Hai Bo, pairing old and new photographs of the same sitters, reflects on the passage of time and the absence of those who have died. Finally, Zhang Peili’s “Continuous Reproduction 25 Times” (1993), here represented by an early frame, steadily degrades a Mao-era photograph of smiling peasant girls to invoke the decreasing power of communist ideology.

‘East and West’

The next section, “East and West,” shows how Chinese artists critiqued and contested the growing influence of Western culture and consumerist values.

In “Hello Mr. Hong” (1998), Hong Hao slyly inserts himself as a Westernized business man into an image of upper-class consumption. For “Long March in Panjiayuan B” (2004), Hong digitally assembled an elaborate photo collage of memorabilia and propaganda associated with the Long March, a still-celebrated tactical retreat by Communist forces during the Chinese Civil War. Hong acquired these items not from historical archives, but at the famous Panjiayuan Bejing flea market, popular with international tourists, highlighting the changing cultural importance of this once-powerful visual iconography.

Wang Qingsong, working with a Beijing film studio and frequently casting himself as protagonist, constructed highly stylized photographic sets that suggest futuristic stage or film performances. In “Prisoner” (1998), Wang firmly grips Coca-Cola cans stacked to resemble steel bars. Tong Dazhuang’s “Untitled (Round Digital Collage Series)” (2006) mixes scores of notable portraits, variously sourced from cartoons, glossy lifestyle magazines and historical photographs, including from China’s history, into receding concentric circles. For “Chinese Landscape (Zhouzheng Garden and Liu Garden)” (1998) Hong Lei photographed a classical garden designed to mimic a pastoral setting, then digitally transformed the scene with blood-red water, clouds and streaks— a symbolic reference to the wounds of modernization.

‘Performance and the Body’

The third and final section, “Performance and the Body,” demonstrates how artists used experimental photography and challenging performance art as tools of self-expression. In doing so, they expanded photography into other sensorial realms such as taste, smell and touch.

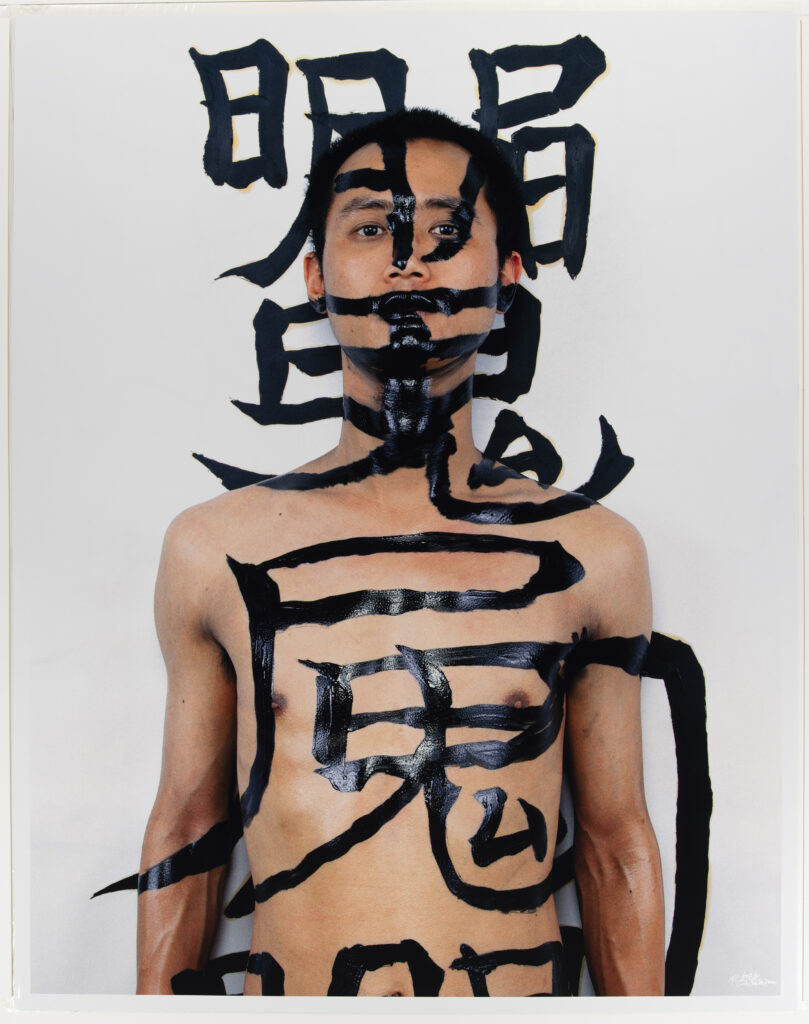

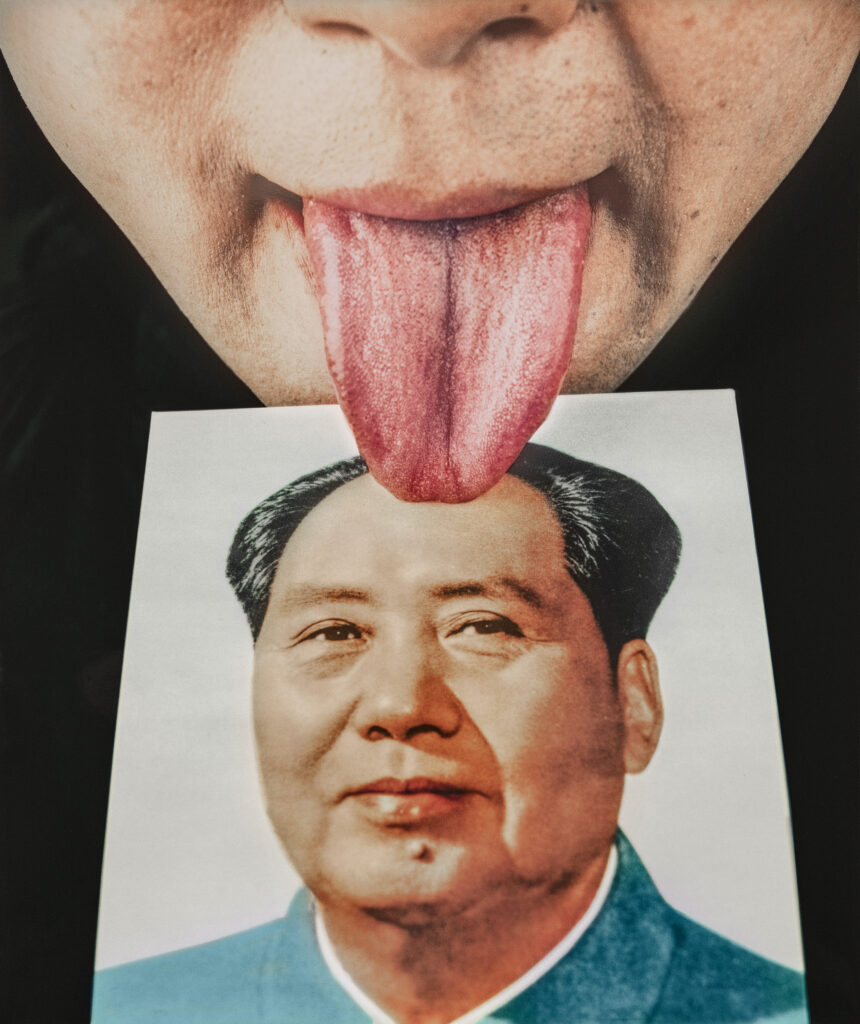

Cang Xin’s “Communication Series” depicts the artist tasting various physical objects — a book, a leaf, a turtle shell, a portrait of Mao. For “Tattoo Series No. 6” (1997), Qiu Zhijie, a classically trained calligrapher, paints bold, literati-style characters onto his face, body and surrounding surfaces. Huang Yan’s “Chinese Landscape Tattoo” series (1999) shows the artist’s chest, arms and hands covered by a traditional mountain scene. Delicately rendered by his wife and fellow artist, Zhang Tiemei, the image metaphorically links body and landscape, as well as individual and national artistic heritage. These impactful works demonstrate how Chinese avant-garde artists uniquely employed their bodies to challenge traditional art and explore the self.

Zhang Huan’s “Foam” series (1998) shows the artist’s face slathered in white bubbles, family photos held in his mouth. Zhang appears again in Rong Rong’s “East Village Beijing No. 11” (1994), from the “East Village Beijing” series. The portrait shows Zhang preparing to perform “12 Square Meters,” a famously grueling test of physical and mental endurance. Coated in honey and fish sauce, the artist would remain perfectly still, ignoring the buzzing flies, his stoic demeanor a powerful aesthetic meditation on, and counterpoint to, the violence of the Cultural Revolution.

Organizers and support

“Looking Back Toward the Future: Contemporary Photography from China” is curated by Sabine Eckmann, the William T. Kemper Director and Chief Curator at the Kemper Art Museum, with Elizabeth Mangone and Stephanie Nebenfuehr as curatorial research assistants.

In addition to Warsh, leadership support is provided by the William T. Kemper Foundation. All exhibitions at the Kemper Art Museum are supported by members of the Director’s Circle, with major annual support provided by Emily and Teddy Greenspan and additional generous annual support from Michael Forman and Jennifer Rice, Julie Kemper Foyer, Joanne Gold and Andrew Stern, David and Dorothy Kemper, Ron and Pamela Mass, and Kim and Bruce Olson. Further support is provided by the Hortense Lewin Art Fund, the Ken and Nancy Kranzberg Fund, and members of the Kemper Art Museum.

Visitors and events

“Looking Back Toward the Future: Contemporary Photography from China” will open Feb. 27 with a panel discussion featuring director and chief curator Sabine Eckmann in conversation with collector Larry Warsh and artist Wang Qingsong. The panel will begin at 5:30 p.m. in Steinberg Hall Auditorium. A public reception will immediately follow from 6:30– 8:30 p.m. in the Kemper Art Museum.

Other related events this spring will include a focused tour of the exhibition April 3 with Eckmann along with Jianqing Chen and Jiayi Chen, WashU assistant professors. On April 15, Peggy Wang, associate professor of art history and Asian studies at Bowdoin College, will discuss “Being and Becoming in Contemporary Chinese Art” as part of the Sam Fox School Public Lecture Series.

Public tours in American Sign Language, English, Chinese and Spanish will take place on select Saturdays and Sundays throughout the spring. The exhibition will remain on view through July 27.

The Kemper Art Museum is located on WashU’s Danforth Campus, near the intersection of Skinker and Lindell boulevards. Visitor parking is available in the university’s east end garage. Regular hours are 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Mondays and Wednesdays through Sundays. The museum is closed Tuesdays. For more information, call 314-935-4523 or visit kemperartmuseum.wustl.edu. Follow the museum on Facebook, Instagram and YouTube.