“It’s all moving so fast,” said Ian Bogost. “It’s moving so fast that by the time we ask the questions, there are different questions.”

Bogost, an internationally recognized scholar and theorist of digital culture, is the Barbara and David Thomas Distinguished Professor at Washington University in St. Louis. Last spring, he led a weekly, one-credit course titled “How AI Will Change Your Career.”

The format was simple. Each week, the class — about 100 students representing all nine WashU schools — was joined by a prominent expert in a given field, from law and medicine to consulting, publishing, biosecurity and computer science.

“It was like a live podcast,” quipped Bogost, also a professor of film and media studies in Arts & Sciences and of computer science and engineering at the McKelvey School of Engineering. “What are they seeing? How is AI affecting their profession?

“How is it affecting their own work?”

A different conversation

The idea for the class originated in discussions with the Arts & Sciences National Council. Will the jobs for which WashU students are training still exist in a year? In five years? “That’s the question we wanted to ask. And hopefully to answer.”

Though public debates around AI can be dominated by polarizing claims, of both utopian and apocalyptic varieties, Bogost wanted to foster a different conversation. “It wasn’t about resistance or acceptance,” he said. “The assumption we made was: This is happening. So what does it mean that it’s happening?

“Everyone had push-and-pull kinds of comments,” he added. “’This is what we know.’ ‘This is where there appears to be benefit.’ But no one said, ‘This isn’t affecting us at all.’”

Most guests joined virtually, though a few talks were staged live. With one notable exception (more on that below), conversations were not recorded, allowing guests to speak freely about sensitive matters.

Conversations often spanned multiple registers. A prominent trial attorney walked students through a major court case involving AI and copyright. But she also considered how AI tools and capabilities might impact law firms. What work can AI do? What could that mean for partners and associates? How might they do their jobs differently?

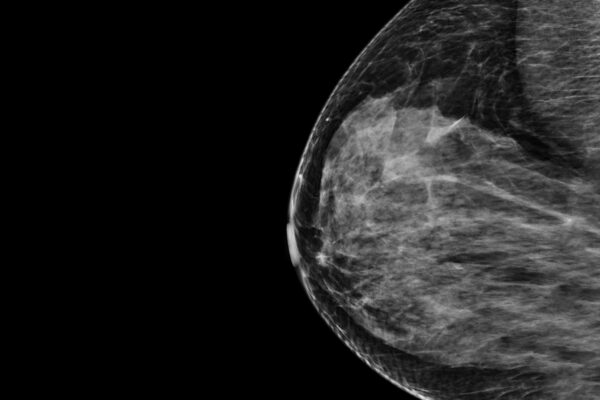

“At times, the AI framework allowed the class to uncover things that weren’t really about AI but that had been happening for a long time and now couldn’t be avoided,” Bogost said. For example, a session on clinical medicine included a substantial discussion of electronic health records.

“As a medical student, you’re trained to help people, to heal people,” Bogost said. “But you’re also going to be doing a lot of bureaucratic work. Can AI assist in that? When it does assist, does it make your job better, or does it just create more paperwork?”

Open but critical

Conversely, while acknowledging that AI will reshape many jobs, few guests seemed to worry that it would ultimately supplant human labor. AI tools are useful not just because they might save some time or money, most agreed, but because they have qualitative differences.

Put another way: AI shouldn’t allow employers simply to do more of the same old thing. It should unlock whole new ways of working.

“In class, the question of what’s the appropriate or inappropriate use of AI was less relevant than what does it mean to try this stuff out?” Bogost said. “What does it mean to experiment? What does it mean to be open but also critical?”

The spring’s final guest, who generously allowed his conversation with Bogost to be recorded and shared, was Andrew “Boz” Bosworth. As chief technology officer at Meta, Boz offered unique insight into how AI, specifically large language models (LLMs), is reshaping computer engineering and software design.

Boz noted that LLMs are very good at certain jobs, such as test engineering — the process of reviewing code, checking for bugs and documenting technical details. This is work that human coders often find tedious or vexing. “Reading someone else’s code is almost as much work as writing your own,” Boz said. “We’re really bad at that. LLMs are amazing at it.”

But if one directs an LLM to generate code from scratch, “you better know what you’re doing … because it can fail in really hilarious ways.”

‘Eat the world’

“We’ve been expecting software to take over and ‘eat the world’ for a long time,” Boz continued. That hasn’t happened. Specific tasks may evolve, specific positions may come and go, but “in all of human history, we’ve never actually created a new invention that drove efficiency (and) reduced employment.”

“These tools are going to exist,” Boz added. “They’re going to be everywhere. So being really good at them is a wise investment.”

Still, Bogost is sympathetic to those unsettled by how quickly the ground is shifting. “Sometimes things happen to you,” Bogost said. “You didn’t choose them, but they happened anyway. Today’s undergrads, their whole postsecondary lives have been colored by big changes that they didn’t choose.

“I think most of us are struggling with exactly what role AI should have,” he continued. That very much includes university professors designing AI curriculums. “I’ve heard from students that, if it’s just a contrivance — Here’s a class where you can use AI! — that’s not floating anyone’s boat.

“But we’re all going through the same moment,” Bogost concluded. “What’s this weird new tool good for? What’s it not good for? How might we control it?

“Let’s figure this out together.”