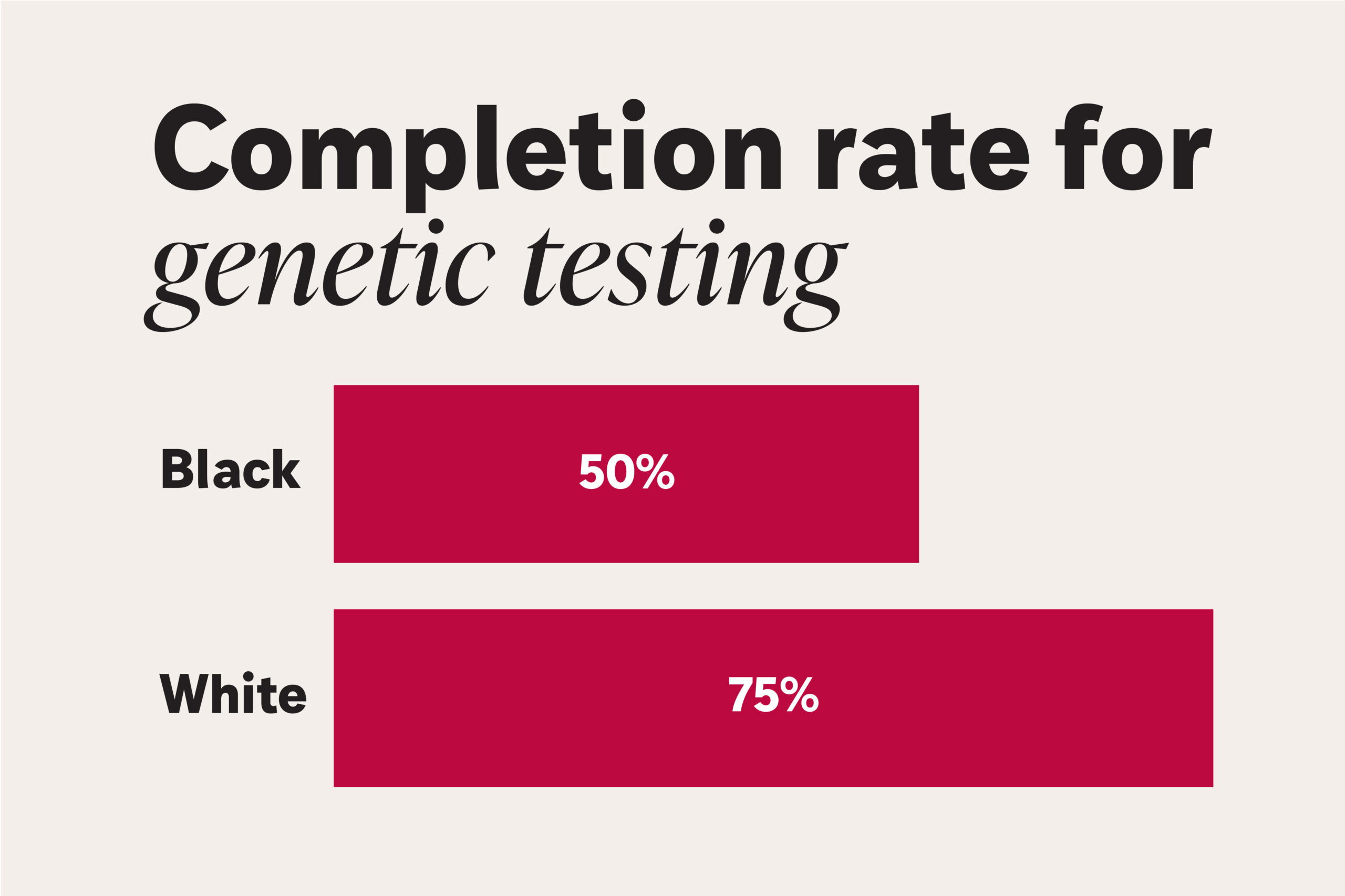

Studies have shown that Black children with serious illnesses are less likely than white children to obtain crucial genetic testing necessary to guide treatment decisions, but the reasons for this disparity have not been fully understood. A new study from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis focused on children with neurological conditions finds that only 50% of Black patients completed genetic testing within a year of doctors referring patients for such testing, compared with 75% of white patients. The results indicate the disparity is due to differences in the type of health insurance kids have and other barriers to accessing care.

The findings, published Feb. 12 in the journal Neurology, highlight the difficulties that patients — particularly Black patients — face in accessing genetic testing to receive accurate diagnoses, the researchers said. The results are already changing practice at WashU Medicine’s pediatric neurology clinic, where a genetic counselor has been embedded to help address some of the access challenges uncovered by the study.

“For children with neurological conditions, genetic testing is essential to obtaining a diagnosis and guiding treatment decisions. If a physician refers a patient for genetic testing, and the patient is unable to get such testing, that really limits the care that physician can provide,” said co-senior author Christina Gurnett, MD, PhD, the A. Ernest and Jane G. Stein Professor of Developmental Neurology and the director of the Division of Pediatric and Developmental Neurology at WashU Medicine. Gurnett is a pediatric neurologist who sees patients at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. “Having genetic information about a patient’s illness determines which medicine we choose. It determines how we monitor for associated conditions, and what we tell families about what they can expect for their child. Disparities in accessing testing translate into inequities in health.”

Genetic testing is recommended for all children with epilepsy or unexplained global developmental delay/intellectual disability, as well as some children with other neurological conditions. Identifying the specific genetic alteration responsible for a child’s symptoms is critical for guiding care decisions, establishing eligibility for precision medicine therapies and clinical trials, and connecting patients and their families with communities of people living with the same condition. Because many genetic conditions are inherited, having precise information can also help parents understand the risks that any future children will inherit such conditions.

Obtaining a genetic test is not a quick or simple process. It can also be expensive, ranging from a few hundred dollars to more than $5,000, depending on the specific test ordered. The child’s doctor must first recognize that genetic testing is indicated and submit a request for approval to their health insurance company. Next, the health insurance company must review the request and provide authorization for the test. Caregivers then typically need to schedule one or more appointments to actually receive the testing.

Gurnett — along with co-senior author Joyce Balls-Berry, PhD, an associate professor of neurology, and first author Jordan Cole, MD, then a neurogenetics fellow at WashU Medicine — collaborated with WashU’s Center for the Study of Race, Ethnicity and Equity to design a study to investigate genetic testing disparities in pediatric neurology and identify ways to address them.

WashU Medicine is a major provider of specialty pediatric neurology care, with patients traveling from throughout the region and surrounding states for care. The researchers examined the records of all 11,371 outpatients seen by WashU Medicine pediatric neurologists between July 2018 and January 2020. They compared genetic testing requests, insurance denials and test completion rates for 1,718 non-Hispanic Black and 8,883 non-Hispanic white patients. (The numbers of patients from other ethnic or racial groups were too small for reliable statistical analysis.) The researchers also gathered data on diagnoses, the type of genetic test ordered, insurance type (public or private), neighborhood social disadvantage and other factors that may influence access to testing.

Black and white children were equally likely to be referred for genetic testing by their neurologist (3.4% of all patients in both groups), but white children were one-and-a-half times as likely as Black children to have received at least one genetic test within a year of the referral. When the researchers controlled for influences such as age, socioeconomic status, number of visits and diagnoses, the disparity widened and white patients were nearly twice as likely to receive genetic testing as were Black patients.

Only half of Black children obtained genetic testing ordered by their neurologists, compared to three-quarters of white children, according to a study by researchers at WashU Medicine. Among all patients, nearly 30% of genetic testing orders remained unfulfilled within a year. WashU Medicine’s pediatric neurologic clinic has added a staff person to address barriers to access. (Image: Sara Moser/WashU Medicine)

This disparity was partially due to insurance denials. For both private and public insurance, there was no racial disparity in denial rates. However, more Black children in the study had public insurance, and public insurance was more likely to deny requests for genetic testing. Children with public insurance – regardless of race – were 41% less likely to complete genetic testing requested by a neurologist than were children with private insurance.

Even after accounting for the difference in insurance, Black families faced additional challenges in accessing genetic testing for their children. More than a quarter (27%) of Black patients were unable to get genetic testing for reasons other than insurance denials, as opposed to 15% of white patients. Other factors, such as traveling for multiple appointments, may have also contributed to the difficulties families faced getting genetic testing for their children.

“Our health-care providers are asking for genetic testing for our patients; the disparity is happening once the families try to access testing,” Balls-Berry said. “We don’t know where this is coming from. There are factors we were not able to measure.”

The racial disparities accompany what is already challenging for families of all backgrounds. Among all pediatric neurology patients who were referred for genetic testing, nearly 30% of genetic testing orders remained unfulfilled within a year. To lower the barriers to testing for patients, the WashU Medicine pediatric neurology clinic hired a genetic counselor to address the specific roadblocks uncovered by the study. Trained in communication as well as in clinical genetics, the counselor can answer questions, guide families through the process of obtaining testing and serve as a bridge between families and insurance companies.

“It’s really important that we don’t let genetic testing become something that only well-resourced people have access to,” Cole said. Now an assistant professor at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus and a pediatric neurologist at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Cole has a larger follow-up study underway with colleagues at WashU Medicine and the University of Colorado. “Our research showed that one of the biggest factors associated with who got genetic testing was race. That is unacceptable. We need to understand better why this is happening so we can address it and ensure that everyone who needs genetic testing has access.”

Cole JJ, Williams JP, Sellitto AD, Baratta LR, Huecker JB, Baldridge D, Kannampallil T, Gurnett CA, Balls-Berry JE. Association of social determinants of health with genetic test request and completion rates in children with neurological disorders. Neurology. Feb.12, 2025. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000210275

The study was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, grant number K12NS098482; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant number UL1TR002345 to the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Science; and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant number P50HD103525 to the Washington University Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).About the Washington University School of Medicine

About Washington University School of Medicine

WashU Medicine is a global leader in academic medicine, including biomedical research, patient care and educational programs with 2,900 faculty. Its National Institutes of Health (NIH) research funding portfolio is the second largest among U.S. medical schools and has grown 56% in the last seven years. Together with institutional investment, WashU Medicine commits well over $1 billion annually to basic and clinical research innovation and training. Its faculty practice is consistently within the top five in the country, with more than 1,900 faculty physicians practicing at 130 locations and who are also the medical staffs of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals of BJC HealthCare. WashU Medicine has a storied history in MD/PhD training, recently dedicated $100 million to scholarships and curriculum renewal for its medical students, and is home to top-notch training programs in every medical subspecialty as well as physical therapy, occupational therapy, and audiology and communications sciences.

Originally published on the WashU Medicine website