The old saying “all politics is local” has become increasingly outdated in a world of growing political polarization. In recent years, federal lawmakers have been motivated to focus more on national politics, WashU political scientist Jaclyn Kaslovsky said.

“Politics has become more competitive, and representatives from both parties feel incentives to coalesce around national brands,” said Kaslovsky, an assistant professor of political science in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

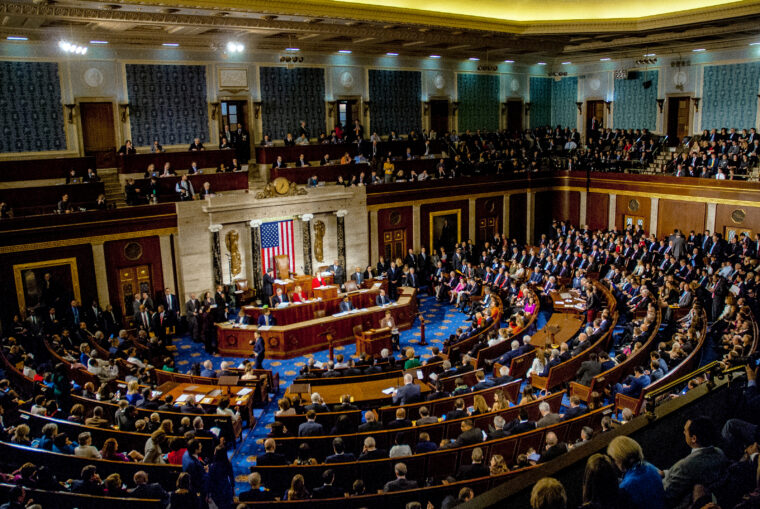

Still, some politicians continue to keep their home districts in mind. In a paper recently published in the American Journal of Political Science, Kaslovsky and co-author Pamela Ban, an assistant professor of political science at the University of California, San Diego, found that women in the U.S. House of Representatives were especially likely to discuss their districts when speaking on the congressional floor. “Women are bringing their constituents into the conversation,” Kaslovsky said.

Kaslovsky and Ban collected transcripts from House hearings from 1999 to 2018 — beginning in the Clinton administration and carrying into the first Trump administration. Then, they created a dictionary of words and phrases that suggest local advocacy, including “community,” “district,” and “my constituents.” The dictionary also included names of cities, counties, and other geographical locations. “When a representative mentions a city or a county in their district, they’re likely talking about local issues,” Kaslovsky said.

Overall, female representatives were more likely than their male counterparts to use these keywords during hearings. This trend could be seen for both parties, but the gender gap was only significant among Democrats. “Republican women have incentives to show they’re true conservatives and that might lead them to focus more on party branding,” Kaslovsky said.

Several factors could be driving women to serve as stronger advocates for their home districts, Kaslovsky said. “Voters seem to hold women to a higher standard,” she said. “Women face a lot of barriers entering politics, so they feel pressure to deliver for their constituents. They procure more funds for the district but also sponsor more legislation.”

Kaslovsky, who joined WashU in July, was previously an assistant professor at Rice University, where she worked with two other researchers who also moved on to WashU’s top-ranked Department of Political Science: Associate Professor Matthew Hayes and Diana Z. O’Brien, the Bela Kornitzer Distinguished Professor.

In her Dean’s Distinguished Lecture in October, O’Brien said that women are underrepresented at every level of politics, from local to national. When women make it to higher office, she said, they tend to be more successful at making laws that help their constituents.

Kaslovsky agreed that the country would be better served if more women were elected. “Currently, women make up less than 30% of the U.S. House of Representatives, so there’s a lack of parity compared with the population,” she said.

But Kaslovsky added that the tendency of female lawmakers to focus on local issues doesn’t automatically make them better representatives.

“I hesitate to make those sorts of value judgments,” she said. “If you’re a constituent, you might want a legislator who’s going to be making a really big impact on a national scale.”

The current U.S. House of Representatives includes several high-profile women on both sides of the aisle who frequently weigh in on national political issues, including Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., and Marjorie Taylor Greene, R-Ga.

“Ocasio-Cortez is often held up as a face of the Democratic Party, and her constituents seem to like that,” Kaslovsky said. “But it’s also not clear if she and other women are really trying to go against stereotypes to become national brands or if the media is just more focused on their behaviors.”

The 125 women in the U.S. House of Representatives bring a wide range of ideologies, personalities, speaking styles and areas of focus to the job, Kaslovsky said. But they all face some of the same gender-based expectations and pressures: “Constituents expect them to deliver.”