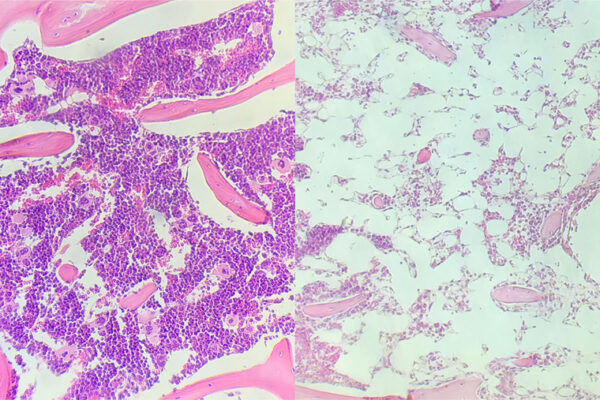

Adding a new drug to standard care for stem cell transplant recipients may reduce a life-threatening side effect, according to an early-stage clinical trial conducted at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. The trial showed that patients being treated for various blood cancers tolerated the investigational drug — called itacitinib —and experienced lower-than-expected rates of graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), in which the donor’s stem cells attack the patient’s healthy tissues.

The study is online in the journal Blood.

“We have to be cautious about interpreting the results of a small study, but the rates of graft-versus-host disease were unexpectedly low,” said senior author John F. DiPersio, MD, PhD, the Virginia E. & Sam J. Golman Endowed Professor of Medicine. “We saw no severe GvHD, and the rates of relapse were lower than expected in these high-risk patients. Low GvHD rates and low relapse resulted in very encouraging survival for the patients in this study. These early results are compelling, and we hope to conduct a bigger randomized controlled clinical trial to be able to evaluate efficacy.”

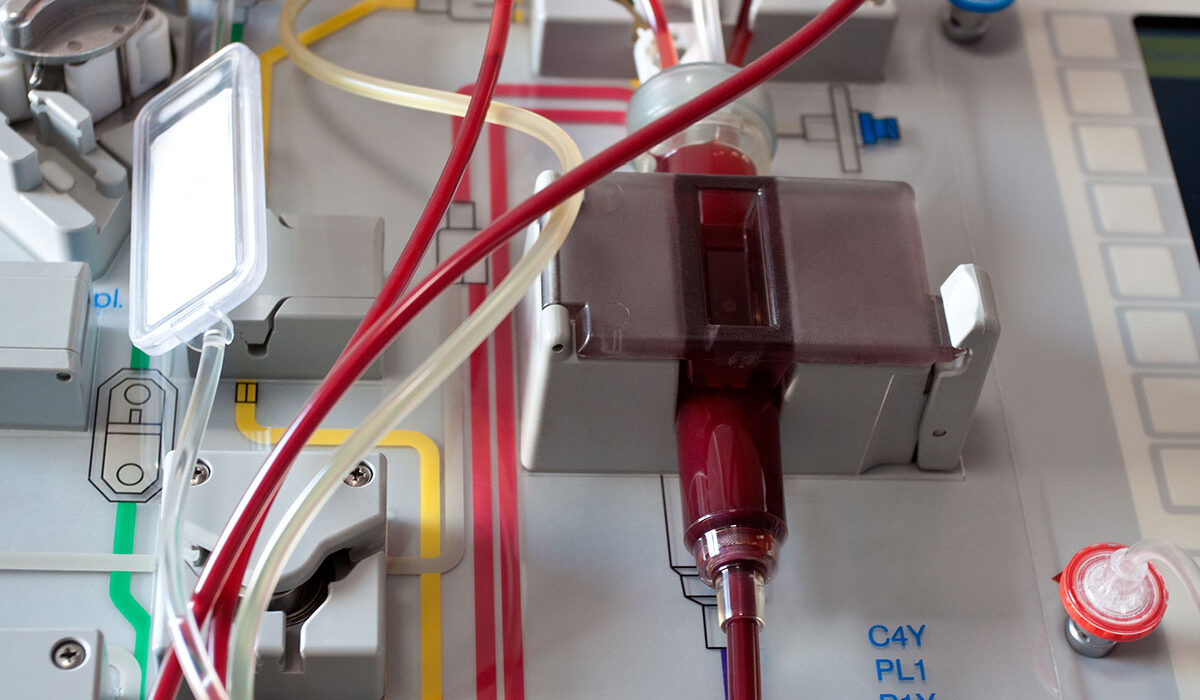

Conducted at Siteman Cancer Center, based at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and WashU Medicine, this Phase I trial involved patients who received a particular stem cell transplant — called a “half-match” — in which half of the key proteins of a patient’s immune system matched those of the donor’s stem cells. Stem cell transplantation is standard care for multiple types of blood cancers, such as leukemia and lymphoma.

A fully matched stem cell donor is preferred for stem cell transplant patients as it reduces the risk of graft-versus-host disease. But recruiting such a donor is often difficult and seeking one out can delay treatment. A patient’s parent or child is automatically a half-matched donor, and siblings are half-matched 50% of the time, making such donors far easier to find for most patients. Half-match stem cell transplants have become more common over the past decade as treatments to reduce graft-versus-host disease have improved, making such transplants safer.

“Half-matched transplants have increased dramatically in recent years, so improving the safety and effectiveness of this procedure is a big goal and has the potential to impact a lot of patients,” DiPersio said.

The trial included 42 patients, most of whom had been diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome, among other, rarer blood cancers. All patients in the study received itacitinib before transplantation and for 4-6 months after transplant, in addition to standard care for prevention of graft-versus-host disease.

None of the 42 patients developed severe (grade 3 or 4) graft-versus-host disease in the first 180 days after the transplant. There was no control group in this study, which was designed to assess the safety but not the efficacy of the treatment. Even so, historical data suggest 10 – 15% of patients would experience severe graft-versus-host disease with standard treatment, according to the investigators. Therefore, statistically, four to six patients in this sample size would be expected to develop severe forms of the disease.

After one year, 89% of patients had no chronic graft-versus-host disease. Two patients developed moderate or severe chronic graft-versus-host disease at that same timepoint, and they were treated with additional therapies. Overall survival at one year was 80%. This is on the high end of what is typically seen in such patients, whose survival can range from 60 – 80% at one year.

The investigational drug itacitinib is one of several JAK inhibitors under investigation for their potential to prevent graft-versus-host disease when given before a stem cell transplant, which would be a new use for this therapy. JAK inhibitors work by blocking the activity of specific enzymes that contributes to inflammation.

“Some other JAK inhibitors are already approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease after it develops,” said first author Ramzi Abboud, MD, an assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Oncology at WashU Medicine. “We are interested in investigating these drugs as a possible way to prevent graft-versus-host disease by giving them before the transplant. We suspect that JAK inhibitors will have a place in prevention of this life-threatening side effect of stem cell transplants. We and other groups are evaluating these kinds of drugs in clinical trials using a variety of approaches. This study is encouraging, and we expect to know more about how best to use these prevention strategies in the coming years.”

Abboud R, Schroeder MA, Rettig MP, Jayasinghe RG, Gao F, Eisele J, Gehrs L, Ritchey J, Choi J, Abboud CN, Pusic I, Jacoby M, Westervelt P, Christopher M, Cashen A, Ghobadi A, Stockerl-Goldstein K, Uy GL, DiPersio JF. Itacitinib for prevention of graft-versus-host disease and cytokine release syndrome with T cell replete peripheral blood haploidentical transplantation. Blood. Nov. 22, 2024. DOI: 10.1182/blood.2024026497.

This work was supported by the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center, Biostatistics Core and Clinical Trials Core; the Bursky Center for Human Immunology and Immunotherapy, Immunomonitoring Laboratory; and the Tumor Procurement Core, funded via the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Comprehensive Cancer Center support grant P30 CA091842; and the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1TR002345 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the NIH. Additional support was provided by the American Society of Hematology Clinical Research Training Institute; the American Society of Hematology Research Training Award for Fellows; and the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number K12 CA167540; an NCI Outstanding Investigator Award, grant number R35 CA210084; the Leukemia SPORE, grant number P50 CA171963; and an NCI Research Specialist Award, grant number R50 CA211782. This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Incyte Corporation provided itacitinib and funding to perform this investigator-initiated study. Incyte had no role in designing the trial, conducting the study or writing the manuscript.

About Washington University School of Medicine

WashU Medicine is a global leader in academic medicine, including biomedical research, patient care and educational programs with 2,900 faculty. Its National Institutes of Health (NIH) research funding portfolio is the second largest among U.S. medical schools and has grown 56% in the last seven years. Together with institutional investment, WashU Medicine commits well over $1 billion annually to basic and clinical research innovation and training. Its faculty practice is consistently within the top five in the country, with more than 1,900 faculty physicians practicing at 130 locations and who are also the medical staffs of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals of BJC HealthCare. WashU Medicine has a storied history in MD/PhD training, recently dedicated $100 million to scholarships and curriculum renewal for its medical students, and is home to top-notch training programs in every medical subspecialty as well as physical therapy, occupational therapy, and audiology and communications sciences.

Originally published on the WashU Medicine website