Aboard the massive research vessel Thomas G. Thompson, sailing 1,600 miles northeast of New Zealand near the Polynesian islands of Samoa, WashU graduate students Adrea Williams and Judy Zhang were thinking deep thoughts.

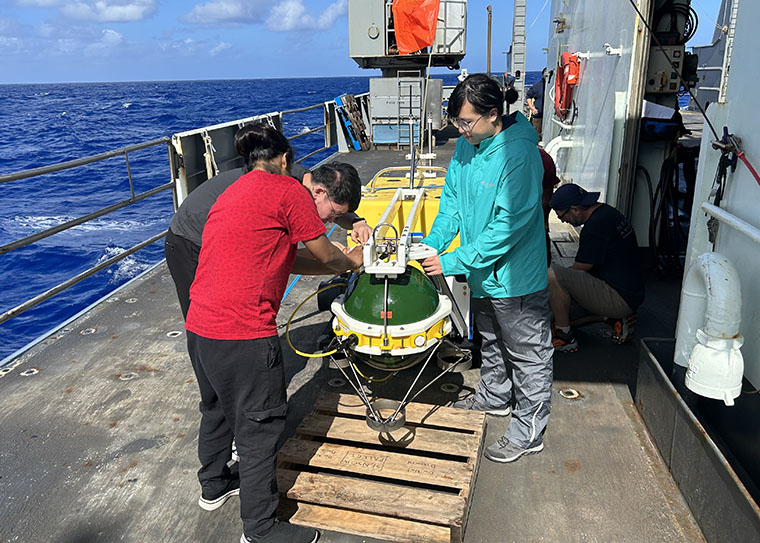

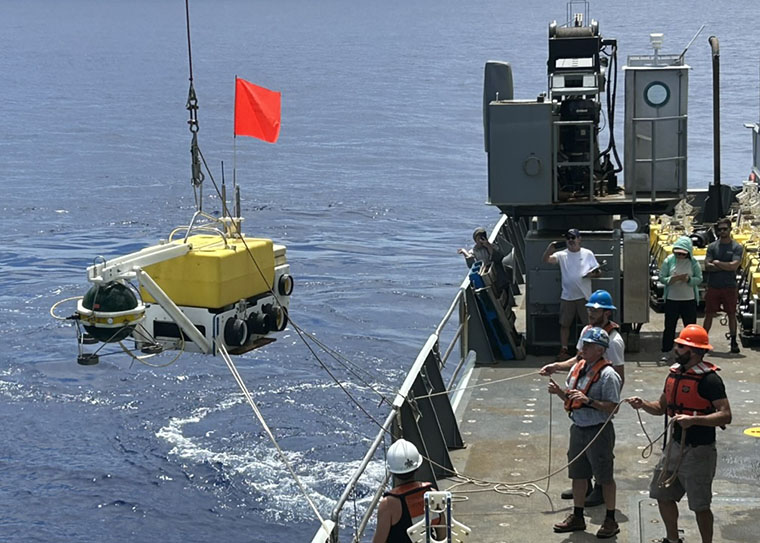

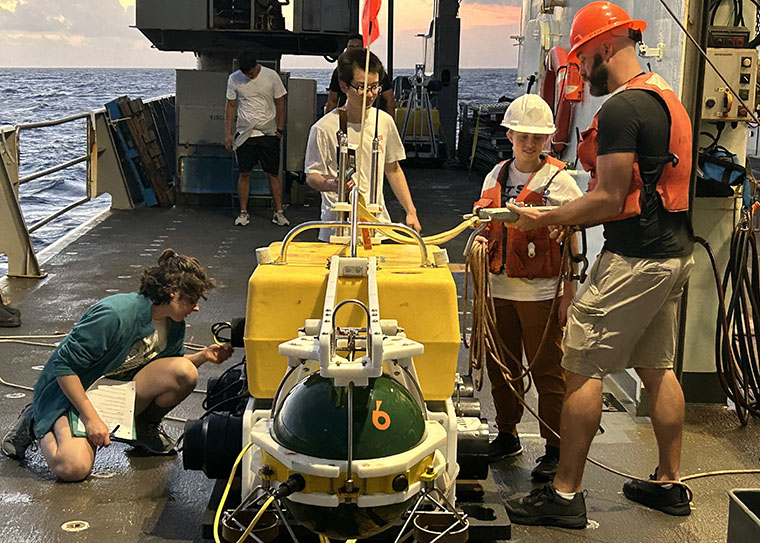

Their team was about to drop 30 seismic monitoring devices up to 6,000 meters (19,000 feet) from the ship’s deck to the ocean floor. Once anchored, the devices were designed to pick up on the inner rumblings of the Earth below them, measuring seismic activity up to 400 miles further down into mantle.

Williams and Zhang nervously awaited the plunge. When the onboard crane finally dropped the first refrigerator-size device overboard, its splash marked the start of an 18-month-long study, an unprecedented duration for seafloor earthquake observation.

If this project is successful, the seismic data that the team will collect will provide extraordinary new detail about an epic geologic clash invisible from the deck of a bobbing ship.

Near Samoa, the dense and ancient Pacific slab descends into the Earth’s interior along a deep oceanic trench. As it slides downward, the sinking slab interacts with materials coming up from the deep mantle, carried by a buoyant upwelling plume. This plume, known as the Samoa plume, is the volcanic hotspot responsible for creating the string of scenic islands nearby.

Around the world, examples of volcanic hotspots in close proximity to subducting plates are rare. This one in the south Pacific is known as the Samoa-Tonga system; another such clash plays out near Yellowstone National Park, in the northwest United States.

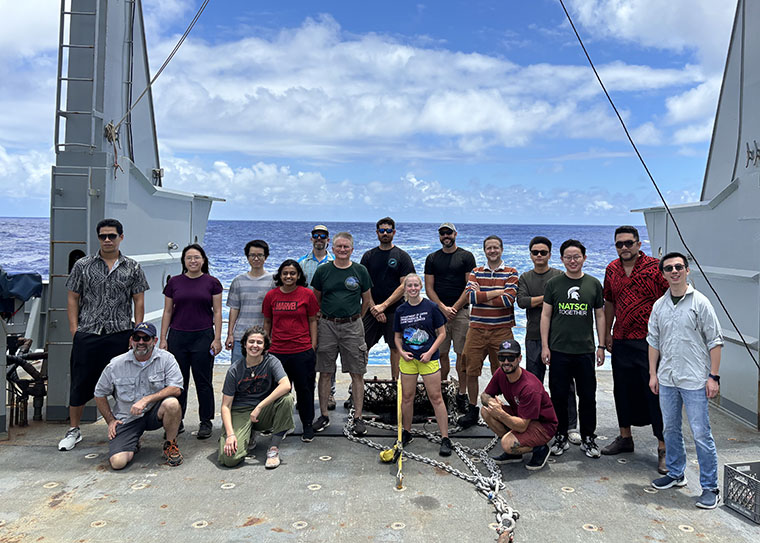

“This is a unique natural laboratory,” said Douglas Wiens, the Robert S. Brookings Distinguished Professor of earth, environmental and planetary sciences in Arts & Sciences, chief scientist on the 28-day research cruise, which was completed last year.

By investigating the competing geologic mechanisms in the Samoa-Tonga system, scientists hope to gain a better understanding of the dynamics of mantle convection — how heat from Earth’s interior is transported to its surface — and also how Earth’s interior has evolved over time.

The project also will allow scientists to observe seismic activity in an area where previous earthquakes have caused deadly and damaging tsunami waves.

Rocks from an unexplored seafloor

The seismic monitoring devices went down to the seafloor, but the team also brought rocks up to the surface.

Zhang, who earned her bachelor’s degree from WashU in 2021, is working with Rita Parai, an associate professor of earth, environmental and planetary sciences in Arts & Sciences, to study these rocks. Zhang and Parai are collaborating with Matthew Jackson, from the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), who was the principal investigator for the dredging portion of the research cruise.

Back at WashU, Zhang is analyzing gases in rocks that the research team scraped from the seamounts bulging up from the seafloor of the Cook Islands, near Samoa.

Some of these seamounts had never been mapped in detail before, let alone sampled.

With these rocks from the hotspot track east of the Tonga trench, Zhang is using geochemistry to determine the ages of submarine eruptions and the deep-mantle origins of the materials.

Among hundreds of pounds of dredged rocks brought onboard during the research cruise, Zhang was delighted to discover a number of xenoliths: unusual greenish-colored pieces of the Earth’s mantle containing olivine, encased in basaltic lava rock.

“These are some really special rocks,” Zhang said. “You don’t usually find mantle xenoliths with golden mica on them in an oceanic setting. That probably means there’s some very specific geological processes enriching these rocks.”

Wiens is working on the Samoa-Tonga project in close collaboration with Shawn Wei, who earned a doctorate from WashU in 2016 and is now at Michigan State University; Jackson and other researchers at UCSB; and experts with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

Zhang already has begun her analysis of the rocks collected on this trip. But Williams and Wiens will have to wait until another research vessel pulls up the seismographs and retrieves their data collectors.

“It seems like with the technology we have these days, we should be able to receive information from them, but we still cannot,” Williams said. “Work at these ocean depths is in many ways like exploring a different planet.”