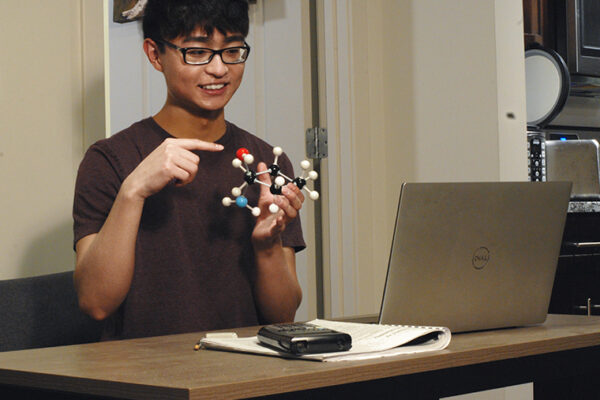

During the ongoing pandemic, many schools with large numbers of vulnerable students — including those with intellectual or developmental disabilities, and minority students living in economically under-resourced communities — have been less likely than other schools to offer in-person instruction, opting instead for virtual learning. But virtual learning is challenging for all students, leaving many at risk of falling behind academically.

To help address this disparity, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have received $8 million from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for two school-based projects — one in St. Louis County and the other in Maryland — aimed at safely returning students and staff to in-person school. Both projects are part of a broader NIH initiative to evaluate whether frequent COVID-19 testing of asymptomatic students, staff and teachers in schools serving under-resourced populations can help to reduce the spread of the virus when such testing is incorporated with proven safety measures. Those measures are masking and social distancing.

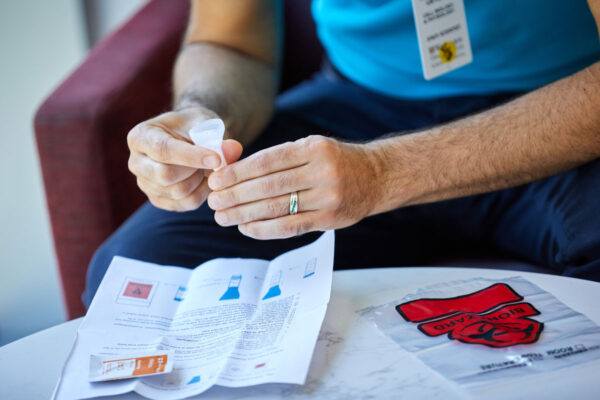

In all, the NIH recently awarded $33 million to fund 10 projects as part of its Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics Underserved Populations (RADx-UP) program. The St. Louis County and Maryland projects will assess the benefits of frequent COVID-19 testing using a saliva test developed at Washington University. In August, the Food and Drug Administration granted emergency use authorization for this fast, easy-to-use diagnostic test, which can detect even minute amounts of virus in a sample of a person’s saliva, making it ideal for screening large groups of students and teachers.

“Students and staff, particularly those in schools with few resources, have not had the same access to in-person instruction during the pandemic, and this is especially worrisome,” said Jason Newland, MD, a professor of pediatrics who is leading the St. Louis County project and has advised multiple school districts in Missouri on plans for reopening schools. “Being in the classroom helps children academically and nurtures their social development.”

The pandemic has disproportionately impacted the education of vulnerable and under-resourced students, who may lack internet access necessary for remote learning and also are missing out on school-based meals, services such as speech or occupational therapy, and after-school programs. Students with intellectual and developmental disabilities in particular rely on daily structure and in-person support for learning and social growth. Due to underlying medical conditions experienced by many such students, those with disabilities also have a higher risk for developing COVID-19 and severe complications of the virus.

“These realities fuel a need to establish a safe return to school,” said Newland, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist who treats patients at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. “Even though cases continue to decline nationally, some areas of the country are still dealing with high infection rates, and we don’t know what next fall and winter will bring.”

The St. Louis project focuses on five school districts in St. Louis County that have high percentages of African American students: Normandy, Jennings, University City, Pattonville and Ferguson-Florissant. Throughout the pandemic, African Americans have been hit hard by COVID-19, with higher rates of cases, hospitalizations and deaths compared with other racial groups. The Washington University team is collaborating closely with the school districts and will offer COVID-19 testing on a voluntary basis; students, staff and their household members with COVID-19 symptoms also will be offered testing. Parents and guardians must provide consent for students to be tested.

Reluctance to return to in-person learning in under-resourced communities is based on concerns that transmission of COVID-19 in schools will further spread the virus to high-risk individuals in the students’ homes and beyond, further exacerbating disparities. But studies led by researchers at Washington University and elsewhere have shown that school-based transmission of COVID-19 is low — even when rates of cases in the community are high — if schools enforce strategies such as masking, social distancing and frequent hand hygiene.

Further, CDC recommendations for in-person, hybrid or remote learning are based, in part, on whether asymptomatic testing can be offered in school settings, and remote learning generally is recommended for communities with high rates of community spread if such testing can’t be offered. But no study has evaluated the benefits of asymptomatic testing in vulnerable populations, Newland noted.

The Maryland project is in collaboration with the Baltimore-based Kennedy Krieger Institute, a nonprofit devoted to individuals with developmental disabilities through clinical care, research and special education. Kennedy Krieger’s four schools, serving more than 500 students from throughout Maryland, also will be sites for frequent surveillance testing of students as well as school staff.

This project expands upon an ongoing RADx-UP project, also led by Washington University, that is evaluating weekly COVID-19 testing in the Special School District in St. Louis County. Since November 2020, more than 5,000 tests have been administered to students and teachers in the Special School District. The Kennedy Krieger researchers will evaluate whether the protocols and communications around frequent testing developed for the Special School District can be implemented in other similar schools. Through surveys, the researchers also will assess why parents are reluctant to return their children to the classroom because such information is crucial to address parents’ concerns.

“Many children with intellectual or developmental disabilities have seen their education disrupted during the pandemic,” said Christina A. Gurnett, MD, PhD, who is co-leading the Maryland project and is the A. Ernest and Jane G. Stein Professor of Developmental Neurology and director of the Division of Pediatric and Developmental Neurology at Washington University. “It can be especially challenging for kids with disabilities to navigate remote learning because they really depend on year-round, in-person physical, occupational and speech therapy, and without it they will regress.

“It is our hope that weekly surveillance testing in this vulnerable community will indicate that in-school transmission of COVID-19 is quite low, providing reassurance that schools are indeed safe for students with disabilities,” said Gurnett, who also serves as neurologist-in-chief at St. Louis Children’s Hospital.

Washington University School of Medicine’s 1,500 faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is a leader in medical research, teaching and patient care, consistently ranking among the top medical schools in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.