A new tool designed to help sports franchises keep the fan experience at stadiums and arenas the safest it can be in this era of COVID-19 has been developed in part by a mathematician at Washington University in St. Louis.

John E. McCarthy, the Spencer T. Olin Professor of Mathematics in Arts & Sciences and chair of the Department of Mathematics and Statistics, helped develop a mathematical model that assesses the risk of attending a public sporting event compared with other high-traffic, consumer-oriented events, such as traveling through airports and flying; attending a class or church service; or going to the grocery store.

The tool is called “Safer Stadia,” and the idea for it was hatched by Delaware North, a privately held company that owns TD Garden in Boston; the Boston Bruins NHL franchise; and operates concessions, premium dining and retail stores at more than 50 sports and entertainment venues around the country (including at Busch Stadium for the St. Louis Cardinals).

As the pandemic changed the course of all public events, Delaware North began looking for a way to safely reopen TD Garden and its operations throughout professional sports — so it tapped into some of the “brightest minds in mathematics and science,” said Jerry Jacobs Jr., co-CEO of Delaware North.

Among the minds behind the Safer Stadia tool was McCarthy, who, in addition to being a nationally renowned mathematician, grew up playing rugby in his native Ireland and became a baseball fan of the Oakland A’s in the late 1980s while a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley.

“And then I moved to St. Louis, and all the people I rooted for in the Bay Area — Tony La Russa, Mark McGwire, even Dennis Eckersley — also moved here,” he said. “And so I became a Cardinals fan.”

McCarthy and his collaborators — Bob Dumas, founder of Customer Marketing Group, a principal of Omnium LLC and a retired affiliate assistant professor at the University of Washington; Johnny Valeriote, CEO of Omnium LLC, who has a master’s degree in computational mathematics from the University of Waterloo; Myles McCarthy, a mathematics and computer science undergraduate at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (and McCarthy’s son); and Siena Ang, Centennial Fellow of computational biology and computer science at Princeton University — were tasked with coming up with a model that would take into account all the details of TD Garden and figure a risk analysis of attending an event there compared with other public events and venues.

The methodology McCarthy and his team devised was risk = hazard x exposure. “I’m a big believer in simple models,” he said. “They’re much more transparent and much more robust.”

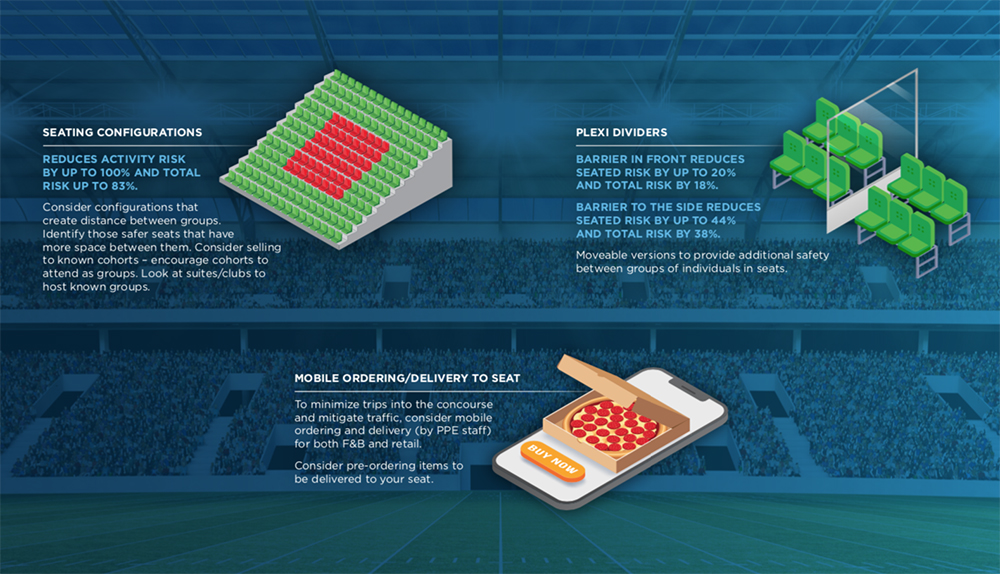

First, the team identified the potential transmission risks in a sports venue: proximity, time and the number of people with whom a person interacts. All of these, it was determined, are factors that can be controlled with mitigating measures.

Next, every part of the stadium experience was factored into a sequence of activities and an estimated amount of time each one takes. Factors such as entering and exiting the stadium; turnstiles and ticketing; walking in the corridors and the width of the concourse; taking the stairs or elevators; the width of the seat, the proximity to the next one and the measure of the pitch from one row to the next.

The researchers also thought about concession stands and condiment carts, the walk from the parking lot — and even bathroom stalls and urinals.

‘The single most important risk factor in a fan experience is seating; and, with mitigation, the risk in everything else is relatively small.

John McCarthy

The research team estimated the risk for each of these activities and then approximated what the total impact would be of different mitigating policies — such as requiring masks, physical distancing in the stadium corridors or leaving some seats empty.

The result was an algorithm that came up with a total risk score for the event. An event with a score of 120, for example, would be twice as risky as one with a score of 60. With this new tool in hand, McCarthy said, teams can measure mitigation strategies and make reasonable, well-informed pitches to their state and local officials month-by-month as the COVID-19 infection rate waxes and wanes in their areas.

“There’s a difference between moderate risk and crazy risk,” McCarthy said. “The point of the model is to assess what’s important in the stadium experience and what’s not. We learned pretty quickly two big takeaways: The single most important risk factor in a fan experience is seating; and, with mitigation, the risk in everything else is relatively small.”

As for those mitigation factors, wearing a mask remains the single most effective way to stop the spread of COVID-19, but will all fans comply? “As part of this initiative a survey of fans asked ‘would you come if you had to wear a mask?’ and 70 percent said yes,” McCarthy said.

“When it all starts back up, there’s going to be reduced occupancy and the fans who attend are going to be the most avid ones, most likely season ticket holders,” McCarthy said. “The punishment for not obeying the rules is you’re going to get kicked out. Teams are going to be able to enforce rules, much more so than can be enforced in other public situations.”

Delaware North is making the tool available to its partners throughout professional sports to help move the industry forward. The tool has been introduced to team and league officials across the NFL, NHL, MLB, NBA and MLS.

“Long range versus short range aerial transmission of SARS-CoV-2,” Aug. 11, 2020, by John E. McCarthy, Washington University in St. Louis; Myles T. McCarthy, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; and Bob A. Dumas Omnium LLC.

“A deterministic linear infection model to inform Risk-Cost-Benefit Analysis of activities during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic,” Aug. 9, 2020, by John E. McCarthy; Washington University in St. Louis; Bob A. Dumas, Ph.D. Omnium LLC; Myles T. McCarthy, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; andBarry D. Dewitt, Ph.D.† Department of Engineering & Public Policy Carnegie Mellon University.