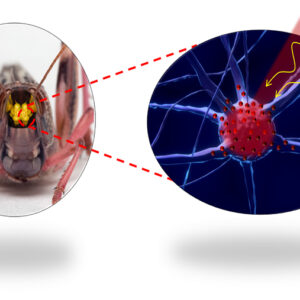

If you want to enhance a locust to be used as a bomb-sniffing bug, there are a few technical challenges that need solving before sending it into the field.

Is there some way to direct the locust — to tell it where to go to do its sniffing? And because the locusts can’t speak (yet), is there a way to read the brain of these cyborg bugs to know what they’re smelling?

For that matter, can locusts even smell explosives?

Yes and yes to the first two questions. Previous research from Washington University in St. Louis has demonstrated both the ability to control the locusts and the ability to read their brains, so to speak, to discern what it is they are smelling. And now, thanks to new research from the McKelvey School of Engineering, the third question has been settled.

The answer, again: ‘yes.’

In a pre-proof published online Aug. 6 in the journal Biosensors and Bioelectronics: X, researchers showed how they were able to hijack a locust’s olfactory system to both detect and discriminate between different explosive scents — all within a few hundred milliseconds of exposure.

They were also able to optimize a previously developed biorobotic sensing system that could detect the locusts’ firing neurons and convey that information in a way that told researchers about the smells the locusts were sensing.

“We didn’t know if they’d be able to smell or pinpoint the explosives because they don’t have any meaningful ecological significance,” said Barani Raman, professor of biomedical engineering. “It was possible that they didn’t care about any of the cues that were meaningful to us in this particular case.”

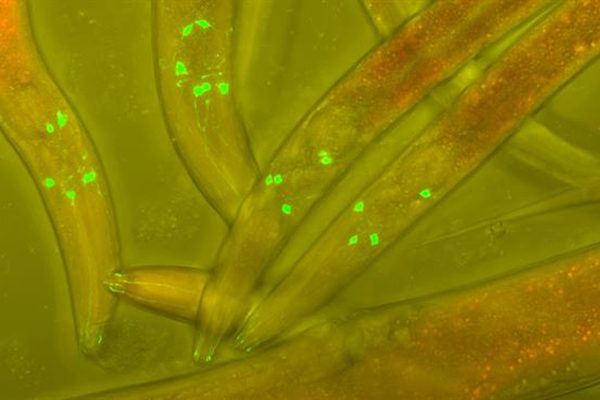

Previous work in Raman’s lab led to the discovery that the locust olfactory system could be decoded as an ‘or-of-ands’ logical operation. This allowed researchers to determine what a locust was smelling in different contexts.

With this knowledge, the researchers were able to look for similar patterns when they exposed locusts to vapors from TNT, DNT, RDX, PETN and ammonium nitrate — a chemically diverse set of explosives. “Most surprisingly,” Raman said, “we could clearly see the neurons responded differently to TNT and DNT, as well as these other explosive chemical vapors.”

With that crucial piece of data, Raman said, “We were ready to get to work. We were optimized.”

Now they knew that the locusts could detect and discriminate between different explosives, but in order to seek out a bomb, a locust would have to know from which direction the odor emanated. Enter the “odor box and locust mobile.”

“You know when you’re close to the coffee shop, the coffee smell is stronger, and when you’re farther away, you smell it less? That’s what we were looking at,” Raman said. The explosive vapors were injected via a hole in the box where the locust sat in a tiny vehicle. As the locust was driven around and sniffed different concentrations of vapors, researchers studied its odor-related brain activity.

The signals in the bugs’ brains reflected those differences in vapor concentration.

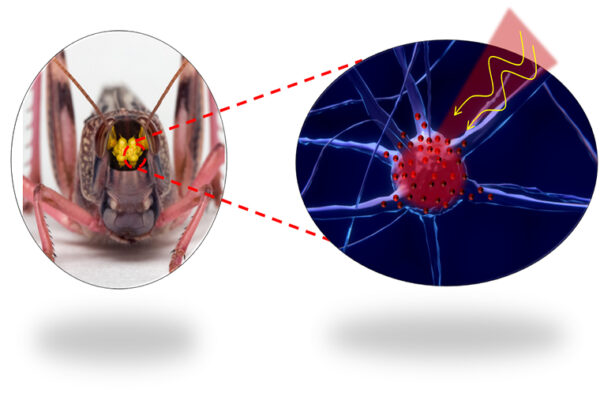

The next step was to optimize the system for transmitting the locusts’ brain activity. The team, which included Shantanu Chakrabartty, the Clifford W. Murphy Professor in the Preston M. Green Department of Electrical & Systems Engineering, and Srikanth Singamaneni, the Lilyan & E. Lisle Hughes Professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering & Materials Science, focused the breadth of their expertise on the tiny locust.

In order to do the least harm to the locusts, and to keep them stable in order to accurately record their neural activity, the team came up with a new surgical procedure to attach electrodes that didn’t hinder the locusts’ movement. With their new instrumentation in place, the neuronal activity of a locust exposed to an explosive smell was resolved into a discernible odor-specific pattern within 500 milliseconds.

“This is not that different from in the old days, when coal miners used canaries.”

Barani Raman

“Now we can implant the electrodes, seal the locust and transport them to mobile environments,” Raman said. One day, that environment might be one in which Homeland Security is searching for explosives.

The idea isn’t as strange as it might first sound, Raman said.

“This is not that different from in the old days, when coal miners used canaries,” he said. “People use pigs for finding truffles. It’s a similar approach — using a biological organism — this is just a bit more sophisticated.”